Record Number

1110

PROSEA Handbook Number

12(2): Medicinal and poisonous plants 2

Taxon

Guazuma ulmifolia Lamk

Protologue

Encycl. 3: 52 (1754).

Family

STERCULIACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 16

Synonyms

Theobroma guazuma L. (1753), Guazuma tomentosa Kunth (1823).

Vernacular Names

Bastard cedar, West Indian elm (En). Bois d'orme, orme d'Amérique (Fr). Indonesia: jati belanda (Malay), jati londo (Javanese).

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Guazuma ulmifolia is a native of tropical America, but long naturalized in various parts of the Old World tropics.

Uses

In Java, at one stage the leaves were a popular herbal tea for losing weight. However, excessive use is injurious to the bowels. The seeds are roasted, pounded and used in decoction as a mild astringent to treat stomach problems. In South America, Central America and the West Indies, various plant parts are used in folk medicine. A decoction of the astringent and mucilaginous bark is a remedy for malaria, diarrhoea and syphilis, and a uterine stimulant. It is applied externally on skin diseases. The inner bark is likewise applied on ulcerous sores. A decoction of the leaves is taken to relieve liver and kidney complaints. A sweetened decoction of the dried and pounded fruits is taken as a cold remedy. A decoction of the root bark is taken to halt dysentery and is given as an enema to relieve haemorrhoids. In Brazil the use is confined to a decoction of the bark that is used indiscriminately for all above mentioned applications and to relieve coughs, bronchitis, asthma and pneumonia. The bark and fruits are also mentioned for losing weight.

The fruit is edible and has an agreeable mucilaginous tissue, but eating too much may cause diarrhoea. The leaves and fruits are used as fodder. The bark is locally used for cordage. Throughout its natural range the wood is used for firewood and charcoal. Guazuma ulmifolia is also planted as a wayside tree in Indonesia. The wood is good and sometimes sold under the name of 'bastard cedar'.

The fruit is edible and has an agreeable mucilaginous tissue, but eating too much may cause diarrhoea. The leaves and fruits are used as fodder. The bark is locally used for cordage. Throughout its natural range the wood is used for firewood and charcoal. Guazuma ulmifolia is also planted as a wayside tree in Indonesia. The wood is good and sometimes sold under the name of 'bastard cedar'.

Production and International Trade

The retail price of powdered bark of Guazuma ulmifolia was about US$ 55/kg in 2001.

Properties

The antisecretory activity of Guazuma ulmifolia bark was examined in vitro, using the isolated rabbit distal colon mounted in an Ussing chamber. Chloride secretion was stimulated by cholera toxin and prostaglandin E-2 (PGE-2). An ethanol extract of the bark completely inhibited cholera toxin-induced secretion if the extract was added to the mucosal bath prior to the toxin. Adding the extract after administration of the toxin had no effect on secretion. The extract did not inhibit PGE-2-induced chloride secretion. These results indicate an indirect antisecretory mechanism. SDS-PAGE analysis furthermore showed that the extract specifically interacted with the A subunit of the toxin. Subsequent bioassay-guided fractionations of the bark extract led to the isolation of polymeric proanthocyanidins which inactivated cholera toxin. The average degree of polymerization of the active compounds ranged from 14.4 to 32.0, and the polymers consisted almost exclusively of (—)-epicatechin units.

Furthermore, bark and leaf extracts of Guazuma ulmifolia have been incorporated in a variety of general screening assays. These include an antihyperglycaemic test, in which a leaf decoction of Guazuma ulmifolia intragastrically administered to temporarily hyperglycaemic rabbits showed a significant decrease of the hyperglycaemic peak and the area under the glucose tolerance curve. Furthermore, an ethanolic leaf extract showed over 90% inhibition in vitro of KB cells.

In addition, extracts have been tested with variable results (often depending on the plant part used) in antimicrobial assays. Examples include a bark extract, which showed good in vitro activity against 5 enterobacteria pathogenic to humans (Escherichia coli, Salmonella enteritidis, Salmonella typhi, Shigella dysenteriae and Shigella flexneri), as opposed to acetone, ethanol and n-hexane extracts of the leaves, which were devoid of activity against a selection of the enteropathogens mentioned (Escherichia coli, Salmonella enteritidis, Shigella flexneri). In a Neisseria gonorrhoeae assay, the bark extract of Guazuma ulmifolia showed no significant activity.

Finally, the major constituents in the essential oil from leaves collected in Brazil, were precocene I (56.0%), 'BETA'-caryophyllene (13.7%) and (2Z,6E)-farnesol (6.6%).

Furthermore, bark and leaf extracts of Guazuma ulmifolia have been incorporated in a variety of general screening assays. These include an antihyperglycaemic test, in which a leaf decoction of Guazuma ulmifolia intragastrically administered to temporarily hyperglycaemic rabbits showed a significant decrease of the hyperglycaemic peak and the area under the glucose tolerance curve. Furthermore, an ethanolic leaf extract showed over 90% inhibition in vitro of KB cells.

In addition, extracts have been tested with variable results (often depending on the plant part used) in antimicrobial assays. Examples include a bark extract, which showed good in vitro activity against 5 enterobacteria pathogenic to humans (Escherichia coli, Salmonella enteritidis, Salmonella typhi, Shigella dysenteriae and Shigella flexneri), as opposed to acetone, ethanol and n-hexane extracts of the leaves, which were devoid of activity against a selection of the enteropathogens mentioned (Escherichia coli, Salmonella enteritidis, Shigella flexneri). In a Neisseria gonorrhoeae assay, the bark extract of Guazuma ulmifolia showed no significant activity.

Finally, the major constituents in the essential oil from leaves collected in Brazil, were precocene I (56.0%), 'BETA'-caryophyllene (13.7%) and (2Z,6E)-farnesol (6.6%).

Description

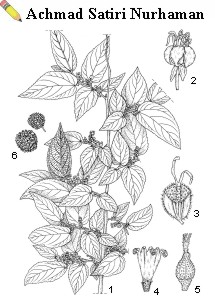

A tree up to 25 m tall, with a diameter at breast height of 30—60 cm, branches stellate-tomentose. Leaves alternate, ovate to oblong or lanceolate, 3—21 cm x 2—6 cm, base unequally cordate, apex long-acuminate, margin serrulate, basally 6-veined, scabrous above, tomentose below; petiole 0.5—2 cm long; stipulate. Inflorescence axillary or terminal, thyrsiform cyme, the ultimate elements scorpioid, 2—4 cm long; bracts and bracteoles subulate, caducous; pedicel 3—6 mm long. Flowers bisexual, up to 8 mm across; calyx tube subglobose, lobes 3, subequal, 2—3 mm long; petals 5, obovate, yellow, the lower part up to 4 mm x 2 mm, cucullate, the appendage divided more than halfway, 4—5 mm long; staminal column of 5 fascicles of 3 anthers, opposite the sepals, alternating with 5 triangular staminodes; ovary superior, globose, 5-locular, styles 5, basally connate. Fruit a subglobose woody capsule, 1.5—4 cm x 1.2—2.5 cm, tubercled, indehiscent, many-seeded. Seed 2.5—4 mm x 1.8—2 mm. Seedling with epigeal germination.

Image

| Guazuma ulmifolia Lamk - 1, flowering twig; 2, flower; 3, petal; 4, staminal column; 5, pistil; 6, fruit |

Growth and Development

Guazuma ulmifolia can be found flowering and fruiting throughout the year. In Java flowering is from April—December. Apparently some seasonality is essential for flowering, as trees do not flower in Singapore.

Other Botanical Information

Guazuma comprises 3 species from the tropics of Central and South America, one (widely) naturalized in the Old World. In South America a further distinction can be made within Guazuma ulmifolia between var. ulmifolia with the capsule remaining closed at maturity and var. tomentella K. Schum. with the capsule incompletely dehiscent by five slits not wide enough to allow the seeds to escape; to a certain extent these differences are correlated with differences in shape of fruit, and outline and indumentum of the leaves.

Ecology

In its natural range Guazuma ulmifolia grows on soil types varying from fertile to barren limestone although it grows best in rich lowland soils, alluvial and clay soils. It is found in both dry and wet forest and commonly encountered in secondary forest, from sea-level up to 1200 m altitude, in areas with a dry season ranging from 4—7 months and an annual rainfall of 700—1500 mm. It is a pioneer species that grows best in full sunlight, it colonizes recently disturbed areas and is found growing along the banks of streams and in pastures.

Propagation and planting

Guazuma ulmifolia can be propagated by direct seeding or by planting cuttings, root stumps or bare-root seedlings. Seeds collected from standing trees are dried in the sun, stored at ambient temperatures and are viable for 5 months. Germination can be enhanced by scarification of the seeds or by soaking them in boiling water for 30 seconds. With fresh seed, germination occurs in 7—14 days at rates of 60—80%. The number of seeds per kg ranges from 100 000 to 225 000 and averages 187 500. Seedlings are ready for transplanting when 30—40 cm tall, after about 15 weeks. With root stumps, plants are left in the nursery for 5—8 months or until they reach a stem diameter of 1.5—2.5 cm.

Husbandry

Guazuma ulmifolia has the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen, regenerates rapidly and is suitable for coppicing. When it has been planted, regular pruning can increase the fodder yield. When pruned four times per year for fodder, it can produce 10 kg/tree dry matter.

Diseases and Pests

Pests of Guazuma ulmifolia are mainly defoliating insects, such as Phelypera distigma, Arsenura armida and Epitragus spp., which can occasionally cause problems.

Harvesting

All plant parts of Guazuma ulmifolia are collected throughout the year whenever the need arises.

Handling After Harvest

Plant parts of Guazuma ulmifolia are used fresh or simply dried for future use.

Genetic Resources and Breeding

Although widespread and common in its natural range, the genetic basis for Guazuma ulmifolia in South-East Asia might be limited. There are no known breeding programmes of Guazuma ulmifolia.

Prospects

The quite specific antisecretory activity of the proanthocyanidins isolated from Guazuma ulmifolia on cholera-toxin is very interesting. Since from time to time, epidemic cholera infections still have a high rate of fatalities, these compounds merit further research to evaluate their possible potential in the development of a future cure for this infective disease.

Literature

Alarcon-Aguilara, F.J., Roman-Ramos, R., Perez-Gutierrez, S., Aguilar-Contreras, A., Contreras-Weber, C.C. & Flores-Saenz, J.L., 1998. Study of the anti-hyperglycemic effect of plants used as antidiabetics. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 61(2): 101—110.

Arriaga, A.M.C., Machado, M.I.L., Craveiro, A.A., Pouliquen, Y.B.M. & Mesquita, A.G., 1997. Volatile constituents from leaves of Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. Journal of Essential Oil Research 9(6): 705—706.

Caceres, A., Cano, O., Samayoa, B. & Aguilar, L., 1990. Plants used in Guatemala for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. 1. Screening of 84 plants against enterobacteria. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 30(1): 55—73.

Hör, M., Heinrich, M. & Rimpler, H., 1996. Proanthocyanidin polymers with antisecretory activity and proanthocyanidin oligomers from Guazuma ulmifolia bark. Phytochemistry 42(1): 109—119.

Morton, J.F., 1981. Atlas of medicinal plants of Middle America, Bahamas to Yucatan. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Illinois, United States. pp. 550—552.

Verdcourt, B., 1995. Sterculiaceae. In: Dassanayake, M.D., Fosberg, F.R. & Clayton, W.D. (Editors): A revised handbook to the flora of Ceylon. Vol. 9. Amerind Publishing Co., New Delhi, India. pp. 409—445.

Arriaga, A.M.C., Machado, M.I.L., Craveiro, A.A., Pouliquen, Y.B.M. & Mesquita, A.G., 1997. Volatile constituents from leaves of Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. Journal of Essential Oil Research 9(6): 705—706.

Caceres, A., Cano, O., Samayoa, B. & Aguilar, L., 1990. Plants used in Guatemala for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. 1. Screening of 84 plants against enterobacteria. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 30(1): 55—73.

Hör, M., Heinrich, M. & Rimpler, H., 1996. Proanthocyanidin polymers with antisecretory activity and proanthocyanidin oligomers from Guazuma ulmifolia bark. Phytochemistry 42(1): 109—119.

Morton, J.F., 1981. Atlas of medicinal plants of Middle America, Bahamas to Yucatan. Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Illinois, United States. pp. 550—552.

Verdcourt, B., 1995. Sterculiaceae. In: Dassanayake, M.D., Fosberg, F.R. & Clayton, W.D. (Editors): A revised handbook to the flora of Ceylon. Vol. 9. Amerind Publishing Co., New Delhi, India. pp. 409—445.

Other Selected Sources

[74] Backer, C.A. & Bakhuizen van den Brink Jr, R.C., 1964—1968. Flora of Java. 3 volumes. Noordhoff, Groningen, the Netherlands. Vol. 1 (1964) 647 pp., Vol. 2 (1965) 641 pp., Vol. 3 (1968) 761 pp.

[135] Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. Revised reprint. 2 volumes. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Vol. 1 (A—H) pp. 1—1240, Vol. 2 (I—Z) pp. 1241—2444.

[219] Cristobal, C.L., 1989. Comentaros acerca de Guazuma ulmifolia (Sterculiaceae). Bonplandia 6(3): 183—196. (in Spanish)

[407] Heyne, K., 1950. De nuttige planten van Indonesië [The useful plants of Indonesia]. 3rd Edition. 2 volumes. W. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage, the Netherlands/Bandung, Indonesia. 1660 + CCXLI pp.

[448] Hör, M., Rimpler, H. & Heinrich, M., 1995. Inhibition of intestinal chloride secretion by proanthocyanidins from Guazuma ulmifolia. Planta Medica 61(3): 208—212.

[662] Matthew, K.M., 1981—1988. The flora of the Tamilnadu Carnatic. 4 volumes. The Rapinat Herbarium, St. Joseph's College, Tiruchirapalli, India.

[724] Nascimento, S.C., Chiappeta, A.A. & Lima, R.M.O.C., 1990. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities in plants from Pernambuco, Brazil. Fitoterapia 61( 4): 353—355.

[786] Perry, L.M., 1980. Medicinal plants of East and Southeast Asia. Attributed properties and uses. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States & London, United Kingdom. 620 pp.

[810] Quisumbing, E., 1978. Medicinal plants of the Philippines. Katha Publishing Co., Quezon City, the Philippines. 1262 pp.

[1028] van Steenis-Kruseman, M.J., 1953. Select Indonesian medicinal plants. Bulletin No 18. Organization for Scientific Research in Indonesia, Djakarta, Indonesia. 90 pp.

[135] Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. Revised reprint. 2 volumes. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Vol. 1 (A—H) pp. 1—1240, Vol. 2 (I—Z) pp. 1241—2444.

[219] Cristobal, C.L., 1989. Comentaros acerca de Guazuma ulmifolia (Sterculiaceae). Bonplandia 6(3): 183—196. (in Spanish)

[407] Heyne, K., 1950. De nuttige planten van Indonesië [The useful plants of Indonesia]. 3rd Edition. 2 volumes. W. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage, the Netherlands/Bandung, Indonesia. 1660 + CCXLI pp.

[448] Hör, M., Rimpler, H. & Heinrich, M., 1995. Inhibition of intestinal chloride secretion by proanthocyanidins from Guazuma ulmifolia. Planta Medica 61(3): 208—212.

[662] Matthew, K.M., 1981—1988. The flora of the Tamilnadu Carnatic. 4 volumes. The Rapinat Herbarium, St. Joseph's College, Tiruchirapalli, India.

[724] Nascimento, S.C., Chiappeta, A.A. & Lima, R.M.O.C., 1990. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities in plants from Pernambuco, Brazil. Fitoterapia 61( 4): 353—355.

[786] Perry, L.M., 1980. Medicinal plants of East and Southeast Asia. Attributed properties and uses. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States & London, United Kingdom. 620 pp.

[810] Quisumbing, E., 1978. Medicinal plants of the Philippines. Katha Publishing Co., Quezon City, the Philippines. 1262 pp.

[1028] van Steenis-Kruseman, M.J., 1953. Select Indonesian medicinal plants. Bulletin No 18. Organization for Scientific Research in Indonesia, Djakarta, Indonesia. 90 pp.

Author(s)

J.L.C.H. van Valkenburg & S.F.A.J. Horsten

Correct Citation of this Article

van Valkenburg, J.L.C.H. & Horsten, S.F.A.J., 2001. Guazuma ulmifolia Lamk. In: van Valkenburg, J.L.C.H. and Bunyapraphatsara, N. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 12(2): Medicinal and poisonous plants 2. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.