Record Number

1476

PROSEA Handbook Number

2: Edible fruits and nuts

Taxon

Artocarpus heterophyllus Lamk

Protologue

Encycl. Méth. 3:210 (1789).

Family

MORACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 56 (tetraploid)

Synonyms

Artocarpus philippensis Lamk (1789), Artocarpus brasiliensis Gomez (1812), Artocarpus maxima Blanco (1837).

Artocarpus integrifolia L.f. is often, but erroneously used as the correct name; it is a synonym for Artocarpus integer (Thunb.) Merr.

Artocarpus integrifolia L.f. is often, but erroneously used as the correct name; it is a synonym for Artocarpus integer (Thunb.) Merr.

Vernacular Names

Jackfruit, jack (En). Jacquier (Fr). Indonesia: nangka, nongko (Javanese). Malaysia: nangka. Papua New Guinea: kapiak. Philippines: langka. Burma: peignai. Cambodia: khnaôr. Laos: miiz, miiz hnang. Thailand: khanun (central), makmi (north-eastern), banun (Chiang Mai). Vietnam: mít.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

The jackfruit is most probably indigenous to and in the past grew wild in the rain forests of the Western Ghats, India. Since time immemorial it has been cultivated; it was introduced and became naturalized in many parts of the tropics, particularly in the South-East Asian region.

Uses

The pulp of young fruit is cooked as vegetable, pickled or canned in brine or curry; pulp of ripe fruit is eaten fresh or made into various local delicacies (e.g. 'dodol' and 'kolak' in Java), chutney, jam, jelly and paste, or preserved as candies by drying or mixing with sugar, honey or syrup. The pulp is also used to flavour ice-cream and beverages, or made into jackfruit honey, or reduced to a concentrate or powder and used for preparing drinks. Addition of synthetic flavours such as esters of 4-hydroxybutyric acid greatly improves the flavour of canned fruit and nectar. The seeds are eaten after boiling or roasting, or dried and salted as table nuts, or ground to make flour which is blended with wheat flour for baking.

Young leaves are readily eaten by cattle and other livestock.

The bark contains about 3.3% tannin, and is occasionally used in making cordage or cloth. A yellow dye extracted from wood particles is used to dye silk and the cotton robes of Buddhist priests. The latex serves as birdlime and is employed as a household cement for mending china and for caulking boats.

The timber is classified as medium hardwood; it is resistant to termite attack, fungal and bacterial decay, easy to season and takes polish beautifully. Thus, though not as strong as teak, jackfruit wood is considered superior to teak for furniture, construction, turnery, masts, oars, implements, and musical instruments. The wood is widely used in Sri Lanka and India; it is even exported to Europe. Roots of older trees are highly prized for carving and picture-framing.

The jackfruit tree is also renowned for its medicinal properties. In China jackfruit pulp and seeds are considered as a cooling and nutritious tonic, useful in overcoming the effects of alcohol. In South-East Asia, the seed starch is used to relieve biliousness and the roasted seeds are regarded as an aphrodisiac. Heated leaves are placed on wounds, and the ash of the leaves burned with maize and coconut shells is used to heal ulcers. Mixed with vinegar the latex promotes healing of abscesses, snakebite and glandular swellings. The bark is made into poultice. The wood has sedative properties and its pith is said to induce abortion. The root is used as a remedy against skin diseases and asthma, and its extract is taken in cases of fever and diarrhoea.

Young leaves are readily eaten by cattle and other livestock.

The bark contains about 3.3% tannin, and is occasionally used in making cordage or cloth. A yellow dye extracted from wood particles is used to dye silk and the cotton robes of Buddhist priests. The latex serves as birdlime and is employed as a household cement for mending china and for caulking boats.

The timber is classified as medium hardwood; it is resistant to termite attack, fungal and bacterial decay, easy to season and takes polish beautifully. Thus, though not as strong as teak, jackfruit wood is considered superior to teak for furniture, construction, turnery, masts, oars, implements, and musical instruments. The wood is widely used in Sri Lanka and India; it is even exported to Europe. Roots of older trees are highly prized for carving and picture-framing.

The jackfruit tree is also renowned for its medicinal properties. In China jackfruit pulp and seeds are considered as a cooling and nutritious tonic, useful in overcoming the effects of alcohol. In South-East Asia, the seed starch is used to relieve biliousness and the roasted seeds are regarded as an aphrodisiac. Heated leaves are placed on wounds, and the ash of the leaves burned with maize and coconut shells is used to heal ulcers. Mixed with vinegar the latex promotes healing of abscesses, snakebite and glandular swellings. The bark is made into poultice. The wood has sedative properties and its pith is said to induce abortion. The root is used as a remedy against skin diseases and asthma, and its extract is taken in cases of fever and diarrhoea.

Production and International Trade

It is not clear why so few statistics are available; jackfruit is, after all, a major fruit and even assumes the role of a staple in periods of food scarcity. Statistics for 1987 show a production of 56.5 million fruits and a total area of 40 700 ha in Thailand, 67 500 t from 13 000 ha in the Philippines and 13 000 t from 1500 ha in Malaysia. In South-East Asia jackfruit is planted mainly in home gardens and mixed orchards; in the 1980s several larger commercial orchards were planted with jackfruit as an intercrop for durian. The large perishable fruit does not lend itself to the export trade, but canned products are exported to Australia, Europe, etc. by canneries in Peninsular Malaysia.

Properties

Edible pulp constitutes 25—40% of the fruit's weight. Food values per 100 g of edible pulp of ripe and young (values in brackets) fruits are as follows: water 72—77.2 g (85.2 g), protein 1.3—2 g (2 g), fat 0.1—0.4 g (0.6 g), carbohydrates 18.9—25.4 g (11.5 g), fibre 0.8—1.1 g (2.6 g), ash 0.8—1.4 g (0.7 g), calcium 22—37 mg (53 mg), phosphorus 18—38 mg (20 mg), iron 0.4—1.1 mg (0.4 mg), sodium 2 mg (3 mg), potassium 407 mg (323 mg), vitamin A 175—540 I.U. (30 I.U.), thiamine 0.03—0.09 mg (0.12 mg), riboflavin 0.05 mg (0.05 mg), niacin 0.9—4 mg (0.5 mg), vitamin C 8—10 mg (12 mg). Energy value is 395—410 kJ (210 kJ) per 100 g. Fresh seed contains 57.6% water and 600 kJ energy per 100 g, mainly in the form of carbohydrates (34.9—38.4 g per 100 g). The non-edible portion of the fruit is rich in pectin and is ideal for making jam.

Description

Medium-sized, evergreen, monoecious tree up to 20(—30) m tall and 80(—200) cm in diameter; all living parts exude viscid, white latex when injured. Bark rough to somewhat scaly, dark grey to greyish- brown. Crown dense, conical in young and shaded trees, becoming rounded or spreading in the older tree. New shoots, twigs and leaves usually glabrous but occasionally short-haired and scabrid. Stipules ovate-acute, 1.5—8 cm x 0.5—3 cm, deciduous and leaving annular scars on the twigs. Leaves thin leathery, obovate-elliptic to elliptic, 5—25 cm x 3.5—12 cm, broadest at or above the middle, base cuneate, margin entire or in young plants often with 1—2 pairs of lobes, apex rounded or blunt with short, pointed tip; dark green and shiny above, dull pale green underneath; petiole 1.5—4 cm long, shallowly grooved on the adaxial side, sparsely hairy. Inflorescences solitary, borne axillary on special lateral, short leafy shoots arising from older branches and main trunk; male flower heads barrel-shaped or ellipsoid, 3—8 cm long and 1—3 cm across, composed of sterile and fertile flowers closely embedded on a central core (receptacle), dark green, stalk 1.5—3.5 cm long and 0.5—1 cm thick, bearing annular ring near the distal end; sterile male flowers with solid perianth; fertile male flowers with tubular, bilobed, 1—1.5 mm long perianth, stamen 1—2 mm long; female heads borne singly or in pairs distal to the position of male heads, cylindrical or oblong, dark green, 5—15 cm long, 3—4.5 cm across, with a distinct annulus at the top end of the stout stalk, subtended by a spathaceous, deciduous bract, 5—8 cm long; female flowers with tubular perianths which are fused at both ends and projecting as 3—7-angled, blunt or pointed, minute pyramidal protuberances topped by spathulate or ligulate styles and stigmas. Fruit (syncarp) barrel- or pear-shaped, 30—100 cm x 25—50 cm, with short pyramidal protuberances or warts; stalk 5—10 cm long, 1—1.5 cm thick; rind ca. 1 cm thick, together with the central core (receptacle) inseparable from the waxy, firm or soft, golden yellow, fleshy perianths surrounding the seeds. Seeds numerous, oblong-ellipsoid, 2—4 cm x 1.5—2.5 cm, enclosed by horny endocarps and subgelatinous exocarps; testa thin leathery; embryo with ventral radicle, cotyledons fleshy, unequal; endosperm very small or absent.

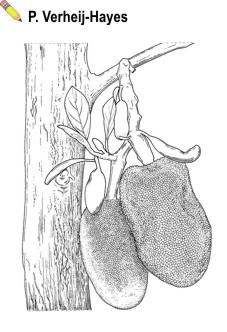

Image

| Artocarpus heterophyllus Lamk - flowering and fruiting branch |

Growth and Development

Trees raised from seed start flowering at the age of 2—8 years. Clonally propagated trees produce fruit within 2—4 years from planting under favourable conditions. Clonal material reaches full production in Malaysia when the trees are 8—15 years old. In suitable environments jackfruit trees bear flowers and fruits throughout the year, but usually there is a major harvest period, in April—August or September—December in Malaysia, January—May in Thailand and in the 'summer' in India. This implies that 3—6 months earlier conditions were particularly favourable for flowering or fruit set. A load of growing fruit may suppress flowering and so accentuate seasonality of production. Whereas female flower heads are only borne on short shoots emerging from the trunk and main limbs, male heads are not restricted to these shoots; they also occur on shoots in the periphery of the tree canopy, particularly in vigorously growing trees. Male and female heads on a cauliflorous shoot develop almost simultaneously, the male head reaching maturity 3—5 days earlier. For the tree as a whole, male and female flowers open over a long period. At anthesis the male heads are dusted with sticky yellow pollen and emit a sweet scent which attracts small insects such as flies and beetles. These may be the pollinating agents, but few insects visit the female heads and in India pollination has been reported to be effected by wind. After anthesis the male heads turn blackish and drop off.

The fertilized female heads develop into mature fruits after 3 months or more, depending on the seedling or clone; at higher altitude or latitude it may take up to 6 months. Unfertilized flowers develop into strap- or string-like structures filling the spaces in between the developing fruitlets. A well-developed fruit may contain up to 500 seeds, each weighing 3—6 g. Germination is hypogeal, but unlike the breadfruit seedling, the cotyledons separate, thus allowing the plumule to emerge without any hindrance. New leaves take 12—15 days to expand. Extension growth in mature trees is slow (up to 3—5 cm per month), but it tends to be continuous.

The fertilized female heads develop into mature fruits after 3 months or more, depending on the seedling or clone; at higher altitude or latitude it may take up to 6 months. Unfertilized flowers develop into strap- or string-like structures filling the spaces in between the developing fruitlets. A well-developed fruit may contain up to 500 seeds, each weighing 3—6 g. Germination is hypogeal, but unlike the breadfruit seedling, the cotyledons separate, thus allowing the plumule to emerge without any hindrance. New leaves take 12—15 days to expand. Extension growth in mature trees is slow (up to 3—5 cm per month), but it tends to be continuous.

Other Botanical Information

In early publications jackfruit was often confused with chempedak (Artocarpus integer), a species native to the western parts of the Malesian region. Jackfruit and chempedak occasionally hybridize; 'Ch/Na', selected and cloned in Malaysia, is regarded as such a hybrid.

Being protandrous and cross-pollinated, the jackfruit shows great variability in many characters, including age of first bearing, and texture, odour and flavour of the fruit. Jackfruits are usually classified into two major types based on the quality of the edible pulp. These are the so-called: (1) koozha chakka (South India), vela (Sri Lanka), khanun lamoud (Thailand), nangka bubur (Indonesia and Malaysia) with generally thin, fibrous, soft and mushy edible pulp, acidulous to very sweet, and emitting a strong odour when ripe; (2) koozha puzham (South India), varaka (Sri Lanka), khanun nang (Thailand), nangka salak (Indonesia), nangka bilulang (Malaysia) with thick, firm or crisp, and less odorous pulp. In both major types there are many cultivars. In Peninsular Malaysia about 30 cultivars have been registered, e.g.: 'Na2': large, roundish fruits which always split at maturity, pulp yellow-green, sweet to slightly acid, coarse and hard in texture, emitting little odour, and having poor storage quality; 'Na29': medium to large fruits containing little latex, pulp yellow, thick, sweet, and good for fresh consumption; and 'Na31': small elongated and long-stalked fruits containing much latex, pulp yellow, sweet, with fine texture and strong aroma; suitable for canning.

Being protandrous and cross-pollinated, the jackfruit shows great variability in many characters, including age of first bearing, and texture, odour and flavour of the fruit. Jackfruits are usually classified into two major types based on the quality of the edible pulp. These are the so-called: (1) koozha chakka (South India), vela (Sri Lanka), khanun lamoud (Thailand), nangka bubur (Indonesia and Malaysia) with generally thin, fibrous, soft and mushy edible pulp, acidulous to very sweet, and emitting a strong odour when ripe; (2) koozha puzham (South India), varaka (Sri Lanka), khanun nang (Thailand), nangka salak (Indonesia), nangka bilulang (Malaysia) with thick, firm or crisp, and less odorous pulp. In both major types there are many cultivars. In Peninsular Malaysia about 30 cultivars have been registered, e.g.: 'Na2': large, roundish fruits which always split at maturity, pulp yellow-green, sweet to slightly acid, coarse and hard in texture, emitting little odour, and having poor storage quality; 'Na29': medium to large fruits containing little latex, pulp yellow, thick, sweet, and good for fresh consumption; and 'Na31': small elongated and long-stalked fruits containing much latex, pulp yellow, sweet, with fine texture and strong aroma; suitable for canning.

Ecology

In its original habitats jackfruit was apparently found mainly in evergreen forests at altitudes of 400—1200 m. The tree extends into much drier and cooler climates than Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg and Artocarpus integer; it fruits up to latitudes 30°N and S in frost-free areas and bears good crops 25°N and S of the equator. However, jackfruit thrives in warm and humid climates below 1000 m. In fact it has poor cold, drought and flooding tolerance, but moderate wind and salinity tolerance. The annual rainfall should be 1500 mm or more and the dry season not too prominent. The tree can be grown on different types of soil but performs best on deep, well-drained, alluvial, sandy or clay loam soils with pH 6.0—7.5.

Propagation and planting

Propagation is normally by seeds, since vegetative propagation is difficult; only in Thailand does vegetative propagation predominate. Successful in vitro propagation has recently been reported from India.

Seed should be obtained from outstanding mother trees; large seeds only are used. Extraction includes thorough washing to remove the slimy coating around the seeds, and removal of the horny part of the pericarp; this improves germination. The seed is sown fresh; if short-term storage is necessary, the seed should not be allowed to dry out. Seeds with about 40% of their original moisture content and stored in air-tight polythene containers at 20°C remain viable for about 3 months. Under suitable conditions germination begins within 10 days and 80—100% germination is achieved within 35—40 days after sowing. The seeds are laid flat or with the hilum facing down to hasten emergence.

Young seedlings are potted at the latest when they have 4 leaves, since older seedlings are hard to transplant. This problem can be avoided by sowing 1—2 seeds directly into containers. The seedlings are best raised under shade (50—70% of full light intensity). They should be planted out when still young — usually less than one year old — that is before the roots grow outside the pot, since disturbance of the roots may be fatal.

It is possible to propagate through cuttings (from forced, etiolated shoots treated with 5 g IBA per litre), air layers (treated with 25 ppm NAA or 100 ppm IBA solution), budding (modified Forkert method or patch budding) and grafting (cleft grafting and wedge grafting), but the results are variable and the methods need to be refined. Budded material of the main clones is usually available in Malaysia. In Australia very good results are obtained by wedge grafting onto young vigorous rootstocks in an enclosed high humidity chamber (polythene covers). In South-East Asia, the only method which is routinely applied on a large scale, i.e. in Thailand, is 'suckle-grafting', a form of inarching: young potted seedling rootstocks are decapitated and inserted in twigs of a selected mother tree. The percentage take is high and the method can be applied at any time of the year.

Various studies have shown that Artocarpus integer (chempedak), Artocarpus hirsutus Lamk, Artocarpus rigidus Blume and Artocarpus altilis (breadfruit) can also serve as rootstocks. In Indonesia the best results were obtained by budding 8—11-month-old chempedak rootstocks.

Orchard trees are spaced 8—12 m apart in square or hexagonal patterns; the usual density is 100—120 trees/ha. The best planting time is at the onset of the rainy season. Shade is provided and the leaves are halved to reduce transpiration. Additional watering may be needed during the first 2 years.

Jackfruit is occasionally planted as an intercrop; in the Philippines, for instance, in coconut groves. In Peninsular Malaysia, jackfruit trees have been used as intercrop and shade trees in durian orchards. In India the trees are intercropped with mango and citrus, and are also used as shade trees for coffee and black pepper. Young jackfruit orchards may be intercropped with annual cash crops such as banana, sweet corn and groundnut. Closely planted rows may serve as windbreaks (Australia).

Seed should be obtained from outstanding mother trees; large seeds only are used. Extraction includes thorough washing to remove the slimy coating around the seeds, and removal of the horny part of the pericarp; this improves germination. The seed is sown fresh; if short-term storage is necessary, the seed should not be allowed to dry out. Seeds with about 40% of their original moisture content and stored in air-tight polythene containers at 20°C remain viable for about 3 months. Under suitable conditions germination begins within 10 days and 80—100% germination is achieved within 35—40 days after sowing. The seeds are laid flat or with the hilum facing down to hasten emergence.

Young seedlings are potted at the latest when they have 4 leaves, since older seedlings are hard to transplant. This problem can be avoided by sowing 1—2 seeds directly into containers. The seedlings are best raised under shade (50—70% of full light intensity). They should be planted out when still young — usually less than one year old — that is before the roots grow outside the pot, since disturbance of the roots may be fatal.

It is possible to propagate through cuttings (from forced, etiolated shoots treated with 5 g IBA per litre), air layers (treated with 25 ppm NAA or 100 ppm IBA solution), budding (modified Forkert method or patch budding) and grafting (cleft grafting and wedge grafting), but the results are variable and the methods need to be refined. Budded material of the main clones is usually available in Malaysia. In Australia very good results are obtained by wedge grafting onto young vigorous rootstocks in an enclosed high humidity chamber (polythene covers). In South-East Asia, the only method which is routinely applied on a large scale, i.e. in Thailand, is 'suckle-grafting', a form of inarching: young potted seedling rootstocks are decapitated and inserted in twigs of a selected mother tree. The percentage take is high and the method can be applied at any time of the year.

Various studies have shown that Artocarpus integer (chempedak), Artocarpus hirsutus Lamk, Artocarpus rigidus Blume and Artocarpus altilis (breadfruit) can also serve as rootstocks. In Indonesia the best results were obtained by budding 8—11-month-old chempedak rootstocks.

Orchard trees are spaced 8—12 m apart in square or hexagonal patterns; the usual density is 100—120 trees/ha. The best planting time is at the onset of the rainy season. Shade is provided and the leaves are halved to reduce transpiration. Additional watering may be needed during the first 2 years.

Jackfruit is occasionally planted as an intercrop; in the Philippines, for instance, in coconut groves. In Peninsular Malaysia, jackfruit trees have been used as intercrop and shade trees in durian orchards. In India the trees are intercropped with mango and citrus, and are also used as shade trees for coffee and black pepper. Young jackfruit orchards may be intercropped with annual cash crops such as banana, sweet corn and groundnut. Closely planted rows may serve as windbreaks (Australia).

Husbandry

Mulching helps to conserve moisture during the dry season. It is recommended to fertilize 2 times per year, at the onset and before the end of the rainy season. The recommended rates vary from 1 kg compound fertilizer per tree per application (Peninsular Malaysia) to 2—3 kg (the Philippines). Pruning is limited to thinning the shoots when the trees are planted and some clearing of the bearing branches to facilitate access to the fruit for wrapping up and harvesting.

Fruit is often protected by bagging or weaving a 'coat' around it, using for instance palm leaflets. This deters rodents and fruit bats, and also attracts ants which keep other insects away.

Fruit is often protected by bagging or weaving a 'coat' around it, using for instance palm leaflets. This deters rodents and fruit bats, and also attracts ants which keep other insects away.

Diseases and Pests

A host of diseases and pests has been reported, but few are specific to jackfruit, and crop protection is not a major concern for growers. However, bacterial dieback caused by Erwinia carotovora is causing increasing losses in jackfruit as well as chempedak. Initially, the bacteria affect the growing shoots, but the disease spreads downwards and eventually kills the tree. To control the disease, chemicals, including trunk injection with antibiotics, are being tested in Malaysia to control the disease. A serious disease in Assam (India) is blossom rot, also called fruit rot or stem rot, caused by Rhizophus artocarpi, leading to crop losses estimated at 15—30%. The inflorescences or the tips of the flowering shoots are infected. The inflorescences are blackened by the sporangia; they rot and drop. Copper fungicides are effective, and control of ants which carry the spores should be considered. Leaf spots of various descriptions can often be found. Different fungi may be involved, including Colletotrichum lagenarium, Phomopsis artocarpina and Septoria artocarpi. The well-known pink disease, Corticium salmonicolor, is a prominent disease of jackfruit. Thorough removal of affected parts is recommended so that the rainy season is entered with a low infection pressure.

Borers are the major pest. Caterpillars of Diaphania caesalis, the shoot borer, tunnel into buds, young shoots and fruit. Removal of affected parts breaks the life cycle since the caterpillar pupates in the tunnel; fruit may be bagged for protection. Bark borers, caterpillars of Indarbela tetraonis and Batocera rufomaculata, can be controlled by fumigating the holes. The brown bud weevil, Ochyromera artocarpi, is a specific jackfruit pest. The grubs bore into tender buds and fruits and the adults feed on the leaves. Infected parts should be destroyed and insecticides may be needed too. Swarms of spittle bugs, Cosmoscarta relata, feed on young leaves. The nymphs live together in a mass of secreted froth, which may be collected and destroyed. Maggots of fruit flies, Dacus dorsalis and Dacus umbrosus, may infest the fruit. To control the pest the fruit is bagged, ripe and overripe fruit is not left around but buried deep in the ground, and bait sprays may be used. Other pests include numerous sucking insects such as mealybugs, aphids, white flies, thrips, etc. and also leaf-webber caterpillars.

Borers are the major pest. Caterpillars of Diaphania caesalis, the shoot borer, tunnel into buds, young shoots and fruit. Removal of affected parts breaks the life cycle since the caterpillar pupates in the tunnel; fruit may be bagged for protection. Bark borers, caterpillars of Indarbela tetraonis and Batocera rufomaculata, can be controlled by fumigating the holes. The brown bud weevil, Ochyromera artocarpi, is a specific jackfruit pest. The grubs bore into tender buds and fruits and the adults feed on the leaves. Infected parts should be destroyed and insecticides may be needed too. Swarms of spittle bugs, Cosmoscarta relata, feed on young leaves. The nymphs live together in a mass of secreted froth, which may be collected and destroyed. Maggots of fruit flies, Dacus dorsalis and Dacus umbrosus, may infest the fruit. To control the pest the fruit is bagged, ripe and overripe fruit is not left around but buried deep in the ground, and bait sprays may be used. Other pests include numerous sucking insects such as mealybugs, aphids, white flies, thrips, etc. and also leaf-webber caterpillars.

Harvesting

Fruit maturity is determined by the following criteria:

(1) dull, hollow sound when tapped; (2) change in skin colour from pale green to greenish- or brownish-yellow; (3) emission of characteristic odour; (4) flattening of the spines and widening of the spaces in between. The stalk is cut with a sharp knife and the fruit carefully lowered to the ground.

(1) dull, hollow sound when tapped; (2) change in skin colour from pale green to greenish- or brownish-yellow; (3) emission of characteristic odour; (4) flattening of the spines and widening of the spaces in between. The stalk is cut with a sharp knife and the fruit carefully lowered to the ground.

Yield

Based on trees grown on experimental stations, the potential yield has been variously estimated as (20—)100—200(—500) fruit/tree per year, each fruit weighing (10—)20—30(—50) kg. However, the actual yield is a tiny fraction of these unrealistic figures which would add up to 2000—4000 kg/tree per year: the average yield is about 70—100 kg/tree per year in Malaysia and the Philippines.

Handling After Harvest

The fruit is collected by wholesalers or taken directly to the market and sold to retailers or cut open and sliced into pieces for direct sale to consumers. Often the fleshy perianths are extracted, cleaned, and sold fresh. During gluts in the supply much fruit is preserved; the flesh is separated from the seeds, washed, pressed and sun-dried with or without addition of sugar or syrup. The products are sold as dried candies. Canneries operate in Peninsular Malaysia.

Genetic Resources

Germplasm collections are available in Indonesia (Centre for Research & Development in Biology, Bogor), the Philippines (Institute of Plant Breeding, Los Baños), Thailand (Plew Horticultural Research Centre), and the United States (US Department of Agriculture, Subtropical Horticultural Research Unit, Miami).

Breeding

No hybridization has been undertaken and rootstock studies have yielded only preliminary results. The cultivars now in use are the result of selection and clonal propagation. Most jackfruits are extremely heterozygous, but the cultivars 'Rudrakshki' and 'Singapore Jack' (= 'Ceylon Jack') in India are said to breed more or less true to type from seed.

Prospects

The prospects for expansion of jackfruit in South-East Asia are rather bleak. The tree and the fruit have several negative attributes: unpredictable yield, both in quantity and timing, crop losses due to diseases and pests, the strong odour, and the large fruit size which limit its potential in export markets. Consequently, the financial returns are low in comparison with, for instance, carambola, durian and guava.

However, there is a wide gap between potential and actual yield. Planting of high-yielding cultivars is the crucial step towards closing the gap.

There are also cultivars with fruit whose smell and taste appeal to the uninitiated consumer; these might be used to penetrate other markets.

Actual yield also lags behind because it is not clear how jackfruit trees function in the course of the year, so that the grower cannot time his operations to raise yield rather than just stimulating growth. Where cultivars replace seedling populations, it becomes easier to study tree phenology since all trees of a cultivar have the same genotype. This means that differences between trees in growth rhythm, flowering time, pollination intensity, fruit set and yield must be due to environmental factors. Thus, the study of the phenology of a cultivar in different environments offers insight into how trees function and gives clues for the elimination of yield-limiting factors.

In other words: the future role of jackfruit hinges on general use of clonal planting material and a better understanding of tree phenology and fruitfulness.

However, there is a wide gap between potential and actual yield. Planting of high-yielding cultivars is the crucial step towards closing the gap.

There are also cultivars with fruit whose smell and taste appeal to the uninitiated consumer; these might be used to penetrate other markets.

Actual yield also lags behind because it is not clear how jackfruit trees function in the course of the year, so that the grower cannot time his operations to raise yield rather than just stimulating growth. Where cultivars replace seedling populations, it becomes easier to study tree phenology since all trees of a cultivar have the same genotype. This means that differences between trees in growth rhythm, flowering time, pollination intensity, fruit set and yield must be due to environmental factors. Thus, the study of the phenology of a cultivar in different environments offers insight into how trees function and gives clues for the elimination of yield-limiting factors.

In other words: the future role of jackfruit hinges on general use of clonal planting material and a better understanding of tree phenology and fruitfulness.

Literature

Abdul Ghani Ibrahim et al., 1980. Plant protection in orchards. In: Othman Yaacob (Editor): Fruit production in Malaysia. Faculty of Agriculture, Universiti Pertanian Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia. pp. 163—190.

Bhutani, D.K., 1978. Pests and diseases of jackfruit in India and their control. Fruits 33: 352—357.

Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Forest Department, Sabah. pp. 399—406.

Ch'ng Guan Choo & Ibrahim Haji Ahmad, 1980. Nutritive value and utilization of Malaysian fruits. In: Othman Yaacob (Editor): Fruit Production in Malaysia. Faculty of Agriculture, Universiti Pertanian Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia. pp. 242—259.

Corner, E.J.H., 1939. Notes on the systematy and distribution of Malayan Phanerogams, II. The jack and the chempedak. Garden's Bulletin Straits Settlements, Singapore 10: 56—81.

Coronel, R.E., 1986. Promising fruits of the Philippines. 2nd edition. College of Agriculture, University of the Philippines at Los Baños. pp. 251—272.

Mohd Yusof bin Hashim & Mohd. Ariff bin Hussein (Editors), 1981. A report on the techno-economic survey of the Malaysian Fruit Industry, 1980. MARDI-UPM, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia. 132 pp.

Molesworth-Allen, B., 1967. Malayan fruits: an introduction to the cultivated species. Donald Moore Press, Singapore. pp. 202—205.

Roy, S.K., Rahman, S.L. & Rita Majundar, 1990. In vitro propagation of jackfruit [Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.] Journal of Horticultural Science 65(3): 335—358.

Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Record No 30: 95—97.

Bhutani, D.K., 1978. Pests and diseases of jackfruit in India and their control. Fruits 33: 352—357.

Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Forest Department, Sabah. pp. 399—406.

Ch'ng Guan Choo & Ibrahim Haji Ahmad, 1980. Nutritive value and utilization of Malaysian fruits. In: Othman Yaacob (Editor): Fruit Production in Malaysia. Faculty of Agriculture, Universiti Pertanian Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia. pp. 242—259.

Corner, E.J.H., 1939. Notes on the systematy and distribution of Malayan Phanerogams, II. The jack and the chempedak. Garden's Bulletin Straits Settlements, Singapore 10: 56—81.

Coronel, R.E., 1986. Promising fruits of the Philippines. 2nd edition. College of Agriculture, University of the Philippines at Los Baños. pp. 251—272.

Mohd Yusof bin Hashim & Mohd. Ariff bin Hussein (Editors), 1981. A report on the techno-economic survey of the Malaysian Fruit Industry, 1980. MARDI-UPM, Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia. 132 pp.

Molesworth-Allen, B., 1967. Malayan fruits: an introduction to the cultivated species. Donald Moore Press, Singapore. pp. 202—205.

Roy, S.K., Rahman, S.L. & Rita Majundar, 1990. In vitro propagation of jackfruit [Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam.] Journal of Horticultural Science 65(3): 335—358.

Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Record No 30: 95—97.

Author(s)

E. Soepadmo

Correct Citation of this Article

Soepadmo, E., 1991. Artocarpus heterophyllus Lamk. In: Verheij, E.W.M. and Coronel, R.E. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2: Edible fruits and nuts. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.