Record Number

1494

PROSEA Handbook Number

2: Edible fruits and nuts

Taxon

Citrus reticulata Blanco

Protologue

Fl. Filip.: 610 (1837).

Family

RUTACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 18

Synonyms

Citrus nobilis Andrews (1810) et auct., non Lour. (1790), Citrus deliciosa Tenore (1840), Citrus chrysocarpa Lushington (1910).

Vernacular Names

Mandarin (En). Tangerine (Am). Mandarinier (Fr). Indonesia: jeruk keprok, jeruk jepun, jeruk maseh. Malaysia: limau langkat, limau kupas, limau wangkang. Philippines: sintones. Cambodia: krauch kvich. Laos: som hot, som lot, liou. Thailand: som khieo waan, som saengthong (Bangkok), ma baang (Chiang Mai). Vietnam: cam sành, cây quit.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Mandarin constitutes one of the three most strongly differentiated species in the genus. Prior to its distribution, selection and hybridization by man, the mandarin would have been limited to South-East Asia, including the Malesian Archipelago. Some writers specify Indo-China as the area of origin, but this is not likely to have been more than the core of the original range. Of the mandarin groups distinguished in the trade, the Satsuma mandarins originated in Japan, the King mandarins in Indo-China, the Mediterranean mandarins in Italy, and the common mandarins in the Philippines. At present mandarins are widely cultivated in all tropical and subtropical regions of the world.

Uses

Because of the loose peel and distinct flavour ranging from consistently sour in some cultivars to very sweet in others, most mandarins are eaten fresh. Segments of fruit are canned and juice is extracted from the fruit. Pectin and essential oils are derived from the rind, which in Indonesia is used in salads.

Production and International Trade

World production of mandarin in 1986—1987 was about 8 million t, which was 15% of the citrus total (mandarin ranking second after the sweet orange, which contributed 68%). The major producing countries are Japan (45% of the world market, mostly Satsuma types), Spain (16%, 'Clementine' and Satsuma), Brazil (8%, 'Ponca', 'Cravo' and 'Murcott'), Italy (6%, 'Clementine'), Morocco (5%, 'Clementine') and United States (4%, 'Clementine', 'Orlando', 'Dancy' and 'Murcott').

In South-East Asia mandarin is the most important citrus crop. In Thailand (561 000 t from 44 800 ha in 1986/1987) and Indonesia (486 000 t in 1986) mandarin production represents more than 80% of all citrus. In the Philippines, however, mandarin (32 000 t in 1981/1982) takes third place after calamondin and pummelo. There is little or no export of mandarin from South-East Asia since it is difficult to meet local demand.

In South-East Asia mandarin is the most important citrus crop. In Thailand (561 000 t from 44 800 ha in 1986/1987) and Indonesia (486 000 t in 1986) mandarin production represents more than 80% of all citrus. In the Philippines, however, mandarin (32 000 t in 1981/1982) takes third place after calamondin and pummelo. There is little or no export of mandarin from South-East Asia since it is difficult to meet local demand.

Properties

The composition of mandarins in Thailand per 100 g edible portion is: water 90 g, protein 0.6 g, fat 0.4 g, carbohydrates 8.6 g, fibre 0.5 g, vitamin A 1062 IU and vitamin C 42 mg. The energy value is 168 kJ/100 g.

Botany

In agriculture and commerce, often the following classification of mandarins is used (all Citrus reticulata Blanco or hybrids according to Swingle):

— The common mandarins (Citrus reticulata Blanco). Description: small spiny tree with slender twigs; leaves broadly to narrowly lanceolate or elliptic with acute tip and base; flowers arising singly or in small clusters in the axils of the leaves; fruit a depressed globose or subglobose berry, with thin, loose peel, easily separating from the segments, bright orange or scarlet-orange when fully ripe; seeds small, pointed at one end, with green embryo. Quite a varied group, including the cultivars: 'Beauty', 'Clementine', 'Dancy', 'Campeona', 'Emperor', 'Ponkan', 'Mandalina', 'Naartje', 'Kinokuni', 'Murcott'. Most of these do well in the tropics but almost every tropical country also has its own preferred cultivars.

— The King mandarins (= Citrus nobilis Loureiro). Tangors. The Indo-China or Cambodia mandarin, or kunenbo from Japan. They are less resistant to cold than many other mandarins. Description: upright spiny or spineless tree; leaves broadly lanceolate, petioles of medium length, narrowly winged; fruit large, peel thick, seeds few to many, segments 12—14.

— The Satsuma mandarins (= Citrus unshiu Marcovitch). The unshiu of Japan; the trees are hardy and cold-resistant, but can also successfully be grown in the tropics. Description: tree usually spreading with drooping branches, nearly spineless; leaves lanceolate with very long, winged petioles; flowers with sterile pollen; fruit medium-sized, seedless, orange, with 10—12 segments. In Japan 5 cultivar groups are distinguished: Wase, Zairai, Owari, Ikeda and Ikiriki.

— The Mediterranean mandarins (= Citrus deliciosa Tenore). The willow leaf mandarin, hardy in the Mediterranean climate, does not store well. Not important for the tropics. Description: tree with drooping branches, more or less spineless; leaves narrowly lanceolate; fruit medium-sized with numerous seeds, 10—12 segments.

For mandarins and mandarin-like fruits, Swingle accepts 3 species, Tanaka 36. The 3 species distinguished by Swingle are:

— Citrus reticulata Blanco. The old name Citrus nobilis Loureiro became invalid when it transpired that the description was based on an interspecific hybrid, a so-called tangor, commonly known as King orange. Citrus reticulata Blanco var. austera Swingle is the sour mandarin or sunkat, to which the Rangpur lime (synonym: Citrus limonia Osbeck) probably also belongs.

— Citrus indica Tanaka. A wild Citrus sp. from India (Indian wild orange), perhaps of value as rootstock.

— Citrus tachibana (Makino) Tanaka, a wild species from Japan and Taiwan.

Swingle distinguishes 6 groups of hybrids in the commonly cultivated mandarins, of which the tangors (mandarin x sweet orange) and tangelos (mandarin x grapefruit) are the most important; the calamondins (mandarin x kumquat) are widely cultivated in South-East Asia; see the article on x Citrofortunella microcarpa (Bunge) Wijnands.

Of 5 important Indonesian cultivars 'Keprok Siem' is planted most and liked best; it is rather tight-skinned. The loose-skinned cultivars 'Keprok Garut' (a 'Ponkan' hybrid), 'Keprok Batu 55', 'Keprok Madura' and 'Keprok Tejakula' are named after the location where the cultivar got its fame. In Malaysia as well as Thailand a single cultivar dominates, which may be the same as 'Keprok Siem' (from 'Siam'?). The better Malaysian cultivars are 'Limau Kupas Masakhijau' and 'Limau Kupas Manek'.

Most mandarins are facultatively apomictic. Both self- and cross-incompatibility play a role. Biennial bearing is common in mandarin, lowering the average yield. To suppress biennial bearing, as much as 75% of the fruit may be thinned in an 'on' year. In Thailand the harvest is some 10 months after bloom, whereas outside South-East Asia 7—8 months is more usual.

— The common mandarins (Citrus reticulata Blanco). Description: small spiny tree with slender twigs; leaves broadly to narrowly lanceolate or elliptic with acute tip and base; flowers arising singly or in small clusters in the axils of the leaves; fruit a depressed globose or subglobose berry, with thin, loose peel, easily separating from the segments, bright orange or scarlet-orange when fully ripe; seeds small, pointed at one end, with green embryo. Quite a varied group, including the cultivars: 'Beauty', 'Clementine', 'Dancy', 'Campeona', 'Emperor', 'Ponkan', 'Mandalina', 'Naartje', 'Kinokuni', 'Murcott'. Most of these do well in the tropics but almost every tropical country also has its own preferred cultivars.

— The King mandarins (= Citrus nobilis Loureiro). Tangors. The Indo-China or Cambodia mandarin, or kunenbo from Japan. They are less resistant to cold than many other mandarins. Description: upright spiny or spineless tree; leaves broadly lanceolate, petioles of medium length, narrowly winged; fruit large, peel thick, seeds few to many, segments 12—14.

— The Satsuma mandarins (= Citrus unshiu Marcovitch). The unshiu of Japan; the trees are hardy and cold-resistant, but can also successfully be grown in the tropics. Description: tree usually spreading with drooping branches, nearly spineless; leaves lanceolate with very long, winged petioles; flowers with sterile pollen; fruit medium-sized, seedless, orange, with 10—12 segments. In Japan 5 cultivar groups are distinguished: Wase, Zairai, Owari, Ikeda and Ikiriki.

— The Mediterranean mandarins (= Citrus deliciosa Tenore). The willow leaf mandarin, hardy in the Mediterranean climate, does not store well. Not important for the tropics. Description: tree with drooping branches, more or less spineless; leaves narrowly lanceolate; fruit medium-sized with numerous seeds, 10—12 segments.

For mandarins and mandarin-like fruits, Swingle accepts 3 species, Tanaka 36. The 3 species distinguished by Swingle are:

— Citrus reticulata Blanco. The old name Citrus nobilis Loureiro became invalid when it transpired that the description was based on an interspecific hybrid, a so-called tangor, commonly known as King orange. Citrus reticulata Blanco var. austera Swingle is the sour mandarin or sunkat, to which the Rangpur lime (synonym: Citrus limonia Osbeck) probably also belongs.

— Citrus indica Tanaka. A wild Citrus sp. from India (Indian wild orange), perhaps of value as rootstock.

— Citrus tachibana (Makino) Tanaka, a wild species from Japan and Taiwan.

Swingle distinguishes 6 groups of hybrids in the commonly cultivated mandarins, of which the tangors (mandarin x sweet orange) and tangelos (mandarin x grapefruit) are the most important; the calamondins (mandarin x kumquat) are widely cultivated in South-East Asia; see the article on x Citrofortunella microcarpa (Bunge) Wijnands.

Of 5 important Indonesian cultivars 'Keprok Siem' is planted most and liked best; it is rather tight-skinned. The loose-skinned cultivars 'Keprok Garut' (a 'Ponkan' hybrid), 'Keprok Batu 55', 'Keprok Madura' and 'Keprok Tejakula' are named after the location where the cultivar got its fame. In Malaysia as well as Thailand a single cultivar dominates, which may be the same as 'Keprok Siem' (from 'Siam'?). The better Malaysian cultivars are 'Limau Kupas Masakhijau' and 'Limau Kupas Manek'.

Most mandarins are facultatively apomictic. Both self- and cross-incompatibility play a role. Biennial bearing is common in mandarin, lowering the average yield. To suppress biennial bearing, as much as 75% of the fruit may be thinned in an 'on' year. In Thailand the harvest is some 10 months after bloom, whereas outside South-East Asia 7—8 months is more usual.

Image

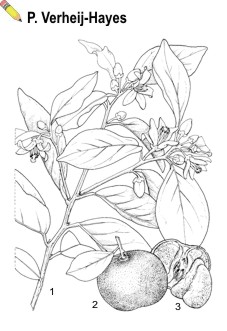

| Citrus reticulata Blanco - 1, flowering branch; 2, fruit; 3, halved fruit and two segments |

Ecology

Mandarins are grown throughout the main citrus belt between 45°N and 35°S. Cultivar groups differ in their ecological requirements, but it is difficult to make sharp distinctions. Most mandarins, particularly the very loose-skinned cultivars, produce their best fruit in a relatively cool climate (highlands between 600—1300 m) and need a pronounced dry season to flower well (e.g. more than 3—4 dry months for 'Keprok Batu' in Java). Other cultivars are less exacting with respect to temperature and do well also in drier lowlands (e.g. the common Thai mandarin). Lastly there are some cultivars which produce prolifically in wet lowlands (e.g. King orange — in Indonesia: jeruk jepun; Satsuma mandarins).

Mandarins are drought-resistant and are able to survive long dry periods. On the other hand air-layered mandarins with a shallow root system are preferred for areas with a high, fluctuating water table where deep-rooting seedling stocks would suffocate.

Mandarins are drought-resistant and are able to survive long dry periods. On the other hand air-layered mandarins with a shallow root system are preferred for areas with a high, fluctuating water table where deep-rooting seedling stocks would suffocate.

Propagation and planting

The common method in South-East Asia is budding, but in Malaysia and Thailand — particularly in the central delta where the water table is high — air layering is the standard method. Rough lemon has been much used as a rootstock, in Indonesia also 'Japanse Citroen' (probably identical to 'Rangpur lime'). A range of other rootstocks has been tested and for the rehabilitation programme in Indonesia the trifoliate 'Troyer' citrange is used as rootstock.

An area of 15—25 m2 per tree (e.g. 5 m x 3 m or 6 m x 4 m) suffices for most mandarins, but in South-East Asia trees are usually spaced further apart, in Indonesia and the Philippines often 5 m x 6 m or 6 m x 6 m. In the typical Thai orchards on converted paddy fields, the spacing is 8 m x 4 m, a single row of trees being planted on a raised bed flanked by ditches. The ditches play a vital role, not only because they provide drainage and because all transport is by boat, but also because the water is used to surface-irrigate the beds and to spray the crop protection chemicals. As the orchards are short-lived due to disease problems, it may be worthwhile to plant double rows on a bed, for instance spaced (5.5 + 2.5) m x 4 m, doubling the number of trees per ha to 600.

An area of 15—25 m2 per tree (e.g. 5 m x 3 m or 6 m x 4 m) suffices for most mandarins, but in South-East Asia trees are usually spaced further apart, in Indonesia and the Philippines often 5 m x 6 m or 6 m x 6 m. In the typical Thai orchards on converted paddy fields, the spacing is 8 m x 4 m, a single row of trees being planted on a raised bed flanked by ditches. The ditches play a vital role, not only because they provide drainage and because all transport is by boat, but also because the water is used to surface-irrigate the beds and to spray the crop protection chemicals. As the orchards are short-lived due to disease problems, it may be worthwhile to plant double rows on a bed, for instance spaced (5.5 + 2.5) m x 4 m, doubling the number of trees per ha to 600.

Husbandry

Husbandry varies greatly in different growing areas. As an example, the husbandry in the central delta of Thailand is described here.

Converting the paddy fields into raised orchard beds is a major operation, largely carried out by contractors with heavy soil-moving equipment. While digging the ditches and canal at the headland, the topsoil is moved to the position of the tree rows. Pulses may be grown as an intercrop in the first few years, after which weeds take over; these are slashed or controlled by herbicides.

Trees come into bearing in the second or third year and 25 t/ha are hoped for in year 6 or 7. Whereas land development is the major investment, crop protection chemicals are the main recurrent cost item (20—30 applications per year). Labour is the other important item (spraying, weeding, manuring, staking, pruning), followed by harvesting costs, manures and fertilizers and stakes.

In spite of the controlled water table, the tree rows are watered regularly during the dry season. A pump mounted on a boat sprays water over the tree rows on both sides of the ditch. In many new mandarin-growing areas the soil is so poor that the trees wilt if irrigation is withheld for any length of time. Hence the orchards cannot be forced into a synchronous cycle of flushing, flowering and fruiting. Protracted flowering leads to a harvest season of 6 months or longer. To improve the situation heavy mulching under the trees is recommended to promote and protect root growth in the topsoil.

Fertilizers are applied in several small doses; manure is only available in areas with animal husbandry. For crop protection a special boat is used: a hole in the bottom lets ditch water into a section of the boat; from a tub with a tap, concentrated chemical drips into the water which is stirred by an overflow of the pump. On each side of the ditch a man sprays a row of trees with a high-pressure gun. This simple system is ingenious, but there is much scope for improvements in design and operation.

Little pruning is carried out, and as the crop can be quite heavy, the slender branches are supported by bamboo stakes.

Converting the paddy fields into raised orchard beds is a major operation, largely carried out by contractors with heavy soil-moving equipment. While digging the ditches and canal at the headland, the topsoil is moved to the position of the tree rows. Pulses may be grown as an intercrop in the first few years, after which weeds take over; these are slashed or controlled by herbicides.

Trees come into bearing in the second or third year and 25 t/ha are hoped for in year 6 or 7. Whereas land development is the major investment, crop protection chemicals are the main recurrent cost item (20—30 applications per year). Labour is the other important item (spraying, weeding, manuring, staking, pruning), followed by harvesting costs, manures and fertilizers and stakes.

In spite of the controlled water table, the tree rows are watered regularly during the dry season. A pump mounted on a boat sprays water over the tree rows on both sides of the ditch. In many new mandarin-growing areas the soil is so poor that the trees wilt if irrigation is withheld for any length of time. Hence the orchards cannot be forced into a synchronous cycle of flushing, flowering and fruiting. Protracted flowering leads to a harvest season of 6 months or longer. To improve the situation heavy mulching under the trees is recommended to promote and protect root growth in the topsoil.

Fertilizers are applied in several small doses; manure is only available in areas with animal husbandry. For crop protection a special boat is used: a hole in the bottom lets ditch water into a section of the boat; from a tub with a tap, concentrated chemical drips into the water which is stirred by an overflow of the pump. On each side of the ditch a man sprays a row of trees with a high-pressure gun. This simple system is ingenious, but there is much scope for improvements in design and operation.

Little pruning is carried out, and as the crop can be quite heavy, the slender branches are supported by bamboo stakes.

Diseases and Pests

As the major citrus species in South-East Asia, mandarin has been hit particularly hard by the greening-virus complex. Tree losses due to root rot (Phytophthora spp.) have become a major concern, for instance in Thailand. Presumably the trees are so weakened by greening and virus diseases, their tolerance of root rot is undermined. As a consequence mandarin growers have to recover their investment in the orchard — and make a living — during the few years after the trees come into bearing and before tree decline and death make exploitation unattractive. Young trees generally look all right, but with the first sizeable crop symptoms of decline come to the fore and the orchard has to be given up 8—15 years after planting. Hence the margins are very narrow and each extra year with a good or fair crop makes a great difference. Hopefully the introduction of certified planting material will give the growers more breathing space.

Harvesting

Fruit should preferably be clipped with scissors, since simple hand-picking often results in a plug of peel being left behind on the tree, particularly in loose-skinned cultivars. In South-East Asia consumers prefer sweet fruit, which means late harvesting.

Yield

Current yield levels in South-East Asia are extremely low, in the order of 5 t/ha per year, mainly due to disease. With healthy trees and a synchronous growth rhythm it should be possible to attain a mean yield of 25 t/ha per year for orchards in full production; potential yield in South-East Asia is probably at least twice as high.

Handling After Harvest

Because of its loose skin mandarin fruit should be handled carefully. The fruit is usually sized and graded (colour and peel quality). Sorted fruit, not exceeding 20 kg, can be packed and stored/transported in wooden boxes or PVC crates. At a temperature of 10°C and 85—90% humidity the fruit can be stored for 4—5 weeks.

Genetic Resources and Breeding

The genetic diversity within the mandarin group is extremely wide. Moreover, the climate affects growth and development to such an extent that it becomes difficult to recognize a familiar cultivar in an unfamiliar environment. Comparison of isozymes is used to clarify the relationships amongst mandarin types. 'Clementine' comprises sexual, freely crossable clones as well as self-incompatible clones. Extensive germplasm collections are kept in a number of stations in Japan, Brazil, Mexico, France (Corsica), Morocco, Turkey and the United States. Within South-East Asia, germplasm — mainly from the country concerned and from the region — has been collected by Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand, the Ministry of Agriculture Research and Development Institute, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and the Horticultural Research Station in Batu, Indonesia.

Cultivars need to be adapted to the local environment and consumer preferences; hence there is a need for breeding programmes in South-East Asia.

Cultivars need to be adapted to the local environment and consumer preferences; hence there is a need for breeding programmes in South-East Asia.

Prospects

There is great scope for expansion of mandarin production in South-East Asia, provided that tree health can be safeguarded. Healthy trees produce much more and remain productive much longer. The result should be that the price of the fruit drops to a fraction of present levels, bringing the fruit within reach of the majority of the population. Lowered prices will also enhance the competitiveness in export markets and stimulate processing.

Literature

Ashari, S., Aspinall, D. & Sedgley, M., 1989. Identification and investigation of relationships of mandarin types using isozymes analysis. Scientia Horticulturae 40: 305—315.

Hodgson, R.W., 1967. Horticultural varieties of citrus. In: Reuther, W., Webber, H.J. & Batchelor, L.D. (Editors): The citrus industry. Revised edition. Vol. 1. History, botany and varieties. University of California, Berkeley. pp. 496—533.

PCARRD, 1982. The Philippines recommends for Citrus. Los Baños. 63 pp.

Sugiyarto, M., 1989. Review of citrus cultivars in Indonesia. Proceedings of Asian Citrus rehabilitation conference. Malang, 4—14 July 1989. 8 pp.

Tanaka, T., 1954. Species problem in Citrus. Japanese Society for the promotion of Science, Ueno, Tokyo. 152 pp.

Hodgson, R.W., 1967. Horticultural varieties of citrus. In: Reuther, W., Webber, H.J. & Batchelor, L.D. (Editors): The citrus industry. Revised edition. Vol. 1. History, botany and varieties. University of California, Berkeley. pp. 496—533.

PCARRD, 1982. The Philippines recommends for Citrus. Los Baños. 63 pp.

Sugiyarto, M., 1989. Review of citrus cultivars in Indonesia. Proceedings of Asian Citrus rehabilitation conference. Malang, 4—14 July 1989. 8 pp.

Tanaka, T., 1954. Species problem in Citrus. Japanese Society for the promotion of Science, Ueno, Tokyo. 152 pp.

Author(s)

Sumeru Ashari

Correct Citation of this Article

Sumeru Ashari, 1991. Citrus reticulata Blanco. In: Verheij, E.W.M. and Coronel, R.E. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2: Edible fruits and nuts. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.