Record Number

1498

PROSEA Handbook Number

2: Edible fruits and nuts

Taxon

Cyphomandra betacea (Cav.) Sendtner

Protologue

Flora 28: 172 (1845).

Family

SOLANACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 24

Synonyms

Solanum betaceum Cav. (1799).

Vernacular Names

Tree tomato (En). Tomate en arbre (Fr). Tamarillo (commercial fruit name). Indonesia: terong belanda, terong menen. Malaysia: pokok tomato. Thailand: makhua-thetton (Chiang Mai).

Origin and Geographic Distribution

The tree tomato is believed to have originated in the Peruvian Andes. It has been introduced in most tropical highlands, where it often occurs naturalized, in the subtropics and also in some mild temperate areas.

Uses

The fruit is used in a variety of ways, including savoury as well as sweet dishes. The unripe fruit can be used for chutney, curry and sambal (hot, chilli-based condiment), the mature fruit for stews, soups, stuffings and salads. Halves may be seasoned and baked or grilled for use as a vegetable. Only mature tree-ripened fruits grown under favourable conditions develop the full flavour and aroma. Properly ripened fruit is also essential for good quality stews, jellies, jams, desserts and ice-cream toppings. The hard seeds may be strained out after boiling. Lime juice and sugar can be added to taste.

Production and International Trade

Tree tomatoes are widely available in local markets in the tropics during most of the year. The tough skin withstands rough handling, a great advantage for a fruit that grows in often inaccessible highlands. Commercial production and organized marketing are only found in New Zealand, where production amounted to 1600 t from 230 ha in 1977. Export promotion under the name 'tamarillo' has not resulted in general consumer acceptance in Australia, Japan and the United States. Colombia, Brazil, Kenya, and countries in the Far East export small quantities to the European Community, but international trade in the fruit and preserves remains small.

Properties

The fruit skin contains a bitter substance and is removed by peeling or scalding for 4 minutes in boiling water. Changing the water after boiling for 3—4 minutes and reheating can reduce the bitterness and tartness of immature fruit. Per 100 g edible portion the fruit contains: water 85 g, protein 1.5 g, fat 0.06—1.28 g, carbohydrates 10 g, fibre 1.4—4.2 g, ash 0.7 g, vitamin A 150—500 IU and vitamin C 25 mg. Most of the vitamin C is lost in cooking.

Botany

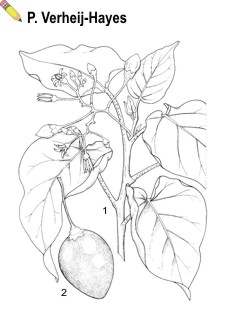

Brittle shrub or tree, 2—3(—8) m tall, trunk short, branches thick. Leaves alternate, simple, cordate-ovate, 10—35 cm x 4—20 cm, entire, soft pubescent, prominently veined, short-pointed, usually near the shoot tips, muskily odorous; petiole 7—10 cm long. Flowers in small, loose axillary clusters near branch tips, pink to light blue, fragrant, about 1 cm diameter, 5-merous; corolla bell-shaped, 5-lobed; stamens 5, on throat of corolla, anthers connivent in a cone about the pistil; ovary 2-celled, many ovules, stigma small. Fruit an obovoid or ovoid berry, 3—10 cm x 3—5 cm, pointed at both ends, pendent, long stalked, with persistent calyx; skin thin, smooth, purple-reddish, orange-red to yellowish; flesh juicy, subacid to sweet, blackish to yellowish. Seeds circular, flat, thin, hard.

Image

| Cyphomandra betacea (Cav.) Sendtner - 1, flowering branch; 2, fruit |

Growth and Development

Seedling trees do not always come true to type. They grow vigorously and may reach a height of 1.5—1.8 m before laterals emerge. The plants grow continuously and easily shed the old leaves. Flowering in the leaf axils follows shoot extension during the season with cool (night?) temperatures. Flowers are self-pollinating; wind and insects assist in pollen transfer, resulting in better fruit set. Fruit ripens over a period of many months. Trees are short-lived; 12 years is the highest recorded lifespan of an orchard.

Other Botanical Information

No named cultivars exist. Fruits are classified according to their colour. Red fruits are often chosen for fresh fruit markets because they look attractive, but they have a stronger, more acid flavour than the yellow ones. The yellow fruit can be canned, but the juice of the red fruit is too abrasive.

Ecology

In the tropics the tree tomato thrives at elevations of 1000 m and more; it still does well above 2000 m if the mean monthly temperature remains above 10°C and if frosts — which kill young plants, and the foliage and shoot tips of mature plants — are exceptional. At low elevations the trees do not flower; cool weather (probably in particular cool nights) promote bloom. That is why the crop ripens in the winter in the subtropics and following a cool spell in the tropics. Flavour develops better under the warm sunny days and cool nights of the dry season in the tropics than during the winter at higher latitudes. Tree tomatoes grow best on well drained soils rich in organic matter and ample moisture. They cannot withstand waterlogging even for periods of a few days. The prolifically bearing and long-lived trees found as shade trees in poultry yards are indicative of the response to manure and 'dry feet'. The trees are shallow-rooted and easily blown over; also the brittle branches are prone to break when loaded with fruit. Thus sheltered locations should be chosen or windbreaks must be provided.

Propagation and planting

Seeds should be selected from true to type plants. In Brazil the seeds are washed, dried in the shade, and placed in a freezer for 24 h. Chilling is claimed to result in virtually 100% germination within 4—6 days. Seed-beds should be prepared with manure or compost and lightly shaded. Propagation from cuttings is an alternative, but it is difficult to ensure freedom from virus infections. Container growing can cut planting-out losses. Cuttings of 1—2-year-old wood 10—30 mm thick and 45—100 cm long can be defoliated and planted directly in the field. Cuttings give low-branched, bushy trees, which may need to be deblossomed to promote growth in the first year. In New Zealand tree tomato is sometimes grafted on related species, in particular Solanum mauritianum Scop., a naturalized weed. Trees on this stock are slightly dwarfed but they bear prolifically and need to be staked.

In New Zealand trees are planted in single or double rows, e.g. at 2.5 m x 2 m or 4.5 m x 1.5 m against (3.5 + 1.5) m x 2 m or (4 + 2.5) m x 3 m, giving densities of 2000—1000 plants per ha. Much higher densities are reported from some other countries. New Zealand growers often plant tree tomato as an intercrop in young citrus orchards.

In New Zealand trees are planted in single or double rows, e.g. at 2.5 m x 2 m or 4.5 m x 1.5 m against (3.5 + 1.5) m x 2 m or (4 + 2.5) m x 3 m, giving densities of 2000—1000 plants per ha. Much higher densities are reported from some other countries. New Zealand growers often plant tree tomato as an intercrop in young citrus orchards.

Husbandry

Orchards need to be well-drained; often the trees are planted on hills or ridges. Because of the shallow root system, deep cultivation should be avoided but mulching is very beneficial. Young seedling trees are cut back to a height of about 1 m to encourage branching, and each year the plants are pruned at the beginning of the crop cycle. This annual pruning consists of cutting back and thinning out the branches that have fruited in order to rejuvenate the bearing wood and to limit tree spread. Time of pruning influences harvest time. For soils of low fertility in New Zealand the fertilizer recommendations are in the order of 110—170 kg N, 35—55 kg P2O5 and 100—200 kg K2O per year. Application is split in a basal dressing just before pruning to stimulate shoot growth, and a top dressing after the last fruits have set to stimulate fruit growth. In the tropics using a generous amount of organic matter and manure when making the hills for planting minimizes the need for additional fertilizer. Irrigation during the dry season is important to sustain growth and to improve fruit size and yield.

Diseases and Pests

The main problems are caused by virus infections, including tree tomato mosaic, cucumber mosaic, Arabis mosaic and one or several unidentified viruses. The viruses spread rapidly — aphids are probably the main vectors — leading to the decline of the orchard. Healthy plants (from seed), grown as far away as possible from older plants, strict orchard hygiene and control of vectors are the principal means of keeping the viruses at bay. Root knot nematodes (Meloidogyne spp.) are also serious and in combination with viruses they result in stunted, unproductive plants; high temperature and moisture stress aggravate matters.

There are a few fungus diseases of which powdery mildew is generally the most troublesome. If serious, it causes the oldest leaves to be shed prematurely. It can be controlled by regular treatment with sulphur or more specific fungicides; the alternative is to maintain a high enough growth rate to offset the loss of leaves. Little can be done to control bacterial blast caused by Pseudomonas syringae.

There are a few fungus diseases of which powdery mildew is generally the most troublesome. If serious, it causes the oldest leaves to be shed prematurely. It can be controlled by regular treatment with sulphur or more specific fungicides; the alternative is to maintain a high enough growth rate to offset the loss of leaves. Little can be done to control bacterial blast caused by Pseudomonas syringae.

Harvesting

Protracted flowering leads to a long harvest season. The fruit does not ripen after harvest and since only fully ripe fruit is of prime quality, the trees have to be picked many times during the harvest season of 5—7 months or more. This adds substantially to the cost of production. Picking is easy, as the fruit stalk breaks readily at an abscission layer 3.5—5 cm from the base of the fruit.

Yield

In Brazil well-spaced trees in full production yield 20-30 kg fruit annually. Nearly the same level is attained in New Zealand, where commercial yields normally are 15—17 t/ha. Trees may bear good crops for 11—12 years, but usually decline after 5—6 years.

Handling After Harvest

Because of its firm flesh and tough smooth skin the fruit handles well. Under normal warm conditions shelf life is about one week, but in cool storage at 3.5°C ± 1°C the fruit keeps for 8 weeks or more. Colletotrichum and Phoma infections in stored fruit may need to be controlled by hot water baths and rewaxing.

Prospects

It is difficult to assess the prospects of the tree tomato in South-East Asia in the absence of data on yield, supply season and domestic uses in the region. If the achievements of New Zealand growers can be matched in the tropical highlands, there is certainly much scope for expansion of production. The yellow fruit with its milder but superior flavour deserves more attention since it is preferred for processing. The production costs for such a labour-intensive crop should be lower than in New Zealand and the same applies to marketing costs if there is a good demand for the fruit in the large domestic markets. Since the fruit travels well, export markets in Asia and elsewhere may offer additional opportunities.

Literature

Anonymous, 1984. What U.S. and Japanese customers think of red tamarillos. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture, August 1984: 34-36.

Fletcher, W.A., 1979. Growing tamarillos. New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture Bulletin 307, Wellington. 27 pp.

Morton, J.F., 1987. Fruits of warm climates. Creative Resource Systems, Winterville, N.C., USA. pp. 437-440

Ochse J.J., Soule, N.J., Dijkman, M.J. & Wehlburg, C., 1961. Tropical and subtropical agriculture. Vol. 1. The Macmillan Company, New York. pp. 744—746.

Fletcher, W.A., 1979. Growing tamarillos. New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture Bulletin 307, Wellington. 27 pp.

Morton, J.F., 1987. Fruits of warm climates. Creative Resource Systems, Winterville, N.C., USA. pp. 437-440

Ochse J.J., Soule, N.J., Dijkman, M.J. & Wehlburg, C., 1961. Tropical and subtropical agriculture. Vol. 1. The Macmillan Company, New York. pp. 744—746.

Author(s)

G. Verhoeven

Correct Citation of this Article

Verhoeven, G., 1991. Cyphomandra betacea (Cav.) Sendtner. In: Verheij, E.W.M. and Coronel, R.E. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2: Edible fruits and nuts. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.