Record Number

1515

PROSEA Handbook Number

2: Edible fruits and nuts

Taxon

Litchi chinensis Sonn.

Protologue

Voy. Indes Orient. Chine 2: 230, t. 129 (1782).

Family

SAPINDACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 28, 30 or 32

Synonyms

— ssp. chinensis: Dimocarpus litchi Lour. (1790), Litchi sinense J. Gmelin (1791), Nephelium litchi Cambess. (1829);

— ssp. philippinensis (Radlk.) Leenh.: Euphoria didyma Blanco (1837) nom. illeg., Litchi philippinensis Radlk. (1914);

— ssp. javensis Leenh.: Litchi chinensis Sonn. f. glomeriflora Radlk. (1932).

— ssp. philippinensis (Radlk.) Leenh.: Euphoria didyma Blanco (1837) nom. illeg., Litchi philippinensis Radlk. (1914);

— ssp. javensis Leenh.: Litchi chinensis Sonn. f. glomeriflora Radlk. (1932).

Vernacular Names

— ssp. chinensis: Lychee, litchi (En). Cérisier de la Chine, litchi de Chine (Fr). Indonesia: litsi (Indonesian), klèngkeng (Javanese), kalèngkeng (Madurese). Malaysia: laici, kelengkang. Philippines: letsias. Burma: kyet-mouk, lin chi, lam yai. Cambodia: kuléén. Laos: ngèèw. Thailand: linchee, litchi, see raaman (Chantaburi). Vietnam: vai, cây vai, tu hú.

— ssp. philippinensis: Philippines: alupag, arupag (Tagalog), mamata (Subanum).

— ssp. javensis: Indonesia: klengkeng (Javanese), lengkeng (Sundanese), kalengkeng (Madurese).

— ssp. philippinensis: Philippines: alupag, arupag (Tagalog), mamata (Subanum).

— ssp. javensis: Indonesia: klengkeng (Javanese), lengkeng (Sundanese), kalengkeng (Madurese).

Origin and Geographic Distribution

The cultivated lychee originated in the region between southern China, northern Vietnam and Malaysia. Wild trees grow in elevated and low rain forests; in some parts of southern China lychee is one of the main forest species. Lychee has a long history in southern China and has undergone intensive selection. It was cultivated by people of Malayan descent possibly as early as 1500 BC, long before the Chinese moved that far south. The spread of lychee to other countries in the last 400 years has been slow, due to the exacting climatic requirement and the short life of its seed. Within South-East Asia only northern Thailand produces lychee in quantity and there is one valley in Bali where the crop is grown commercially. Elsewhere in South-East Asia the trees usually fail to flower, although in Thailand a lowland type lychee bears fruit.

Uses

Lychees are cultivated for their fruit. They have a long history of acceptance in China and many parts of South-East Asia. Traditionally much fruit used to be traded as 'dried lychee nuts', but this form of preservation has been partly replaced by canning. China, Taiwan and Thailand have substantial canning industries. The present destination of the crop in China is: 60% fresh, 20% canned and 20% dried. Lychee fruit can also be processed into juice and wine. Lychee honey is of excellent quality. The fruit, its peel and the seed are used in traditional medicine, decoctions of the root, bark and flowers are gargled. The timber is said to be nearly indestructible.

Production and International Trade

The main producing countries are Taiwan (131 000 t), India (91 860 t), China (61 820 t), Madagascar (35 000 t), Thailand (8401 t), South Africa (5687 t), Australia (1500 t) Mauritius (1000 t) and Reunion (1000 t). There is also interest in the crop in Vietnam, New Zealand and the United States. Production in southern China is centred in Guangdong and Fujian where lychee ranks either 2nd or 3rd in importance behind citrus and longan. Thailand and Taiwan exported about 12 000 t of lychee to Singapore and Hong Kong in 1984. About 2000 t of fruit are exported to Europe, mainly from South Africa, Mauritius and Reunion.

Properties

The food value of lychee lies in its sugar content which ranges from 7—21%, depending on climate and cultivar. Lychee fruits also contain about 0.7% protein, 0.3% fat, 0.7% minerals (particularly Ca and P) and are reasonable sources of vitamins C (64 mg/100 g pulp), A, B1 and B2. The strong appeal of lychee lies in the exquisite aroma of the fruit. In the best cultivars the aril completely covers the seed and may comprise 70—80% of the fruit weight. In some cultivars a high proportion of the seeds aborts. Fruit with these small and shrivelled seeds ('chicken tongue' seeds) are preferred, since they contain a greater proportion of flesh.

Description

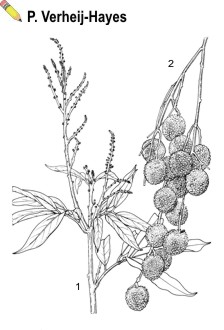

A large, long-lived, evergreen tree up to 30 m tall, with a short stocky trunk; in some cultivars branches crooked or twisting, spreading, forming a crown broader than high; in other cultivars branches fairly straight and upright, forming a compact rounded crown. Leaves alternate, pinnately compound, 2—4(—5)-jugate; petiolules 3—8 mm long; leaflets oblong-lanceolate, (3—)8—11(—16) cm x 1.75—4 cm, chartaceous to coriaceous, glossy and deep green above, glaucous beneath. Inflorescences many-branched panicles, 5—30 cm long, many-flowered; flowers small, yellowish-white, functionally male or female; calyx 4-merous; corolla absent; stamens 6(—10), filaments in male flowers at least twice the length of the calyx, in female flowers very short. Fruit a rounded, ovoid or heart-shaped drupe, ca. 3—3.5 cm in diameter; exocarp thin, leathery, bright red to purplish, nearly smooth or scaly to densely set with flat, conical, acute warts; the fleshy edible portion is the aril, an outgrowth of the seed stalk, in good fruits comprising 70—80% of the fruit weight; aril white and translucent. Seed 10—23 mm x 6—12 mm, brown.

Image

| Litchi chinensis Sonn. - 1, flowering branch; 2, branchlet with fruits |

Growth and Development

Vegetative growth occurs as a series of flushes alternated with periods of dormancy. Flushes last shorter periods and follow one another more rapidly at high temperatures (25—30°C) and constant water supply. The desirable growth rhythm is 2—3 months of vegetative growth after harvest, followed by a rest period 1—2 months before panicle emergence early in the cool season. Panicle and flower development continues uninterrupted and leads to bloom 6—12 weeks after floral induction. Fruit set — at the end of the cool season — normally lasts 4—6 weeks for a single cultivar. Fruit is ready for harvest after 11—16 weeks, completing the crop cycle.

Excessive vegetative growth is a serious problem as it interferes with flowering and fruit set. Trees propagated by air layering usually produce commercial crops after 3—6 years.

Excessive vegetative growth is a serious problem as it interferes with flowering and fruit set. Trees propagated by air layering usually produce commercial crops after 3—6 years.

Other Botanical Information

At present, the genus Litchi Sonn. comprises only the species Litchi chinensis, which can be divided into 3 subspecies:

— ssp. chinensis: twigs slender; leaves 2—4-jugate; flowers in lax cymules, stamens 6(—10); fruits smooth or with pyramidal warts up to 1 mm high. It is the commonly cultivated Chinese fruit tree, probably originating from northern Indo-China; it grows wild in northern Vietnam and Cambodia. In China two cultivar groups are distinguished: the 'water lychee' — with the best cultivars, cultivated in the lowlands, fruits nearly smooth, and the 'mountain lychee' — cultivated in hilly regions, fruits smaller and more prickly, used as a rootstock.

— ssp. philippinensis: twigs slender; leaves 1—2(—3)-jugate; flowers in lax cymules, stamens (6—)7; fruits with pyramidal warts up to 3 mm high. Only known from the Philippines, where it is rather common and widely distributed, but rarely cultivated.

— ssp. javensis: twigs thick; leaves 2—4-jugate; flowers in sessile clusters, stamens 7—11; fruits smooth or with pyramidal warts up to 1 mm high. The plant is only known from cultivation in West Java and southern Indo-China; it may be suited to more humid tropical conditions.

The lychee has undergone intensive selection: the first book on tree fruits in China was devoted to a description of the countless lychee cultivars. The main cultivars in southern China are 'Souey Tung', 'Haak Yip' and 'Wai Chee', followed by 'Tai So', 'Sum Yee Hong', 'Chen Zi', 'Kwai Mai', 'Fay Zee Siu' and 'No Mai Chee'. Production in other countries is based on Chinese cultivars: 'Haak Yip' in Taiwan, 'Tai So' and 'Wai Chee' in Thailand (named 'Hong Huay' and 'Cheng Keng' respectively in Thailand); 'Tai So' in South Africa; and 'Tai So' and 'Bengal' (from India), 'Kwai Mai' (Pink) and 'Wai Chee' in Australia. The only exception is India, where local selections of Chinese imports predominate.

— ssp. chinensis: twigs slender; leaves 2—4-jugate; flowers in lax cymules, stamens 6(—10); fruits smooth or with pyramidal warts up to 1 mm high. It is the commonly cultivated Chinese fruit tree, probably originating from northern Indo-China; it grows wild in northern Vietnam and Cambodia. In China two cultivar groups are distinguished: the 'water lychee' — with the best cultivars, cultivated in the lowlands, fruits nearly smooth, and the 'mountain lychee' — cultivated in hilly regions, fruits smaller and more prickly, used as a rootstock.

— ssp. philippinensis: twigs slender; leaves 1—2(—3)-jugate; flowers in lax cymules, stamens (6—)7; fruits with pyramidal warts up to 3 mm high. Only known from the Philippines, where it is rather common and widely distributed, but rarely cultivated.

— ssp. javensis: twigs thick; leaves 2—4-jugate; flowers in sessile clusters, stamens 7—11; fruits smooth or with pyramidal warts up to 1 mm high. The plant is only known from cultivation in West Java and southern Indo-China; it may be suited to more humid tropical conditions.

The lychee has undergone intensive selection: the first book on tree fruits in China was devoted to a description of the countless lychee cultivars. The main cultivars in southern China are 'Souey Tung', 'Haak Yip' and 'Wai Chee', followed by 'Tai So', 'Sum Yee Hong', 'Chen Zi', 'Kwai Mai', 'Fay Zee Siu' and 'No Mai Chee'. Production in other countries is based on Chinese cultivars: 'Haak Yip' in Taiwan, 'Tai So' and 'Wai Chee' in Thailand (named 'Hong Huay' and 'Cheng Keng' respectively in Thailand); 'Tai So' in South Africa; and 'Tai So' and 'Bengal' (from India), 'Kwai Mai' (Pink) and 'Wai Chee' in Australia. The only exception is India, where local selections of Chinese imports predominate.

Ecology

The lychee is one of the most environmentally sensitive of the tropical tree crops. It is adapted to the tropics and warm subtropics (between 13—32°N and 6—29°S), cropping best in regions with winters that are short, dry and cool (daily maximum below 20—22°C) but frost free, and summers that are long and hot (daily maximum above 25°C) with high rainfall (1200 mm) and high humidity. Good protection from wind is essential for cropping. Year-to-year variations in weather precipitate crop failures, e.g. through untimely rain promoting flushing at the expense of floral development or through poor fruit set following cool damp weather during bloom, even though mean climatic data appear favourable for lychee.

Propagation and planting

Air layering is the main commercial method of propagation and rates of success are usually not less than 95%. Other methods of propagation include grafting (useful for top-working older trees), budding and use of cuttings (for the rapid multiplication of new cultivars). Incompatibility occurs in some scion/rootstock combinations.

Spacing is 6 m x 6 m (280 trees/ha) for upright cultivars such as 'Kwai Mai Pink'. More vigorous cultivars such as 'Tai So', 'Souey Tung' and 'Haak Yip' can be planted at 9—12 m between the rows and 6 m between trees (140—185 trees/ha). Orchards need to be thinned out to 70 trees per ha; the density of the closely planted orchards is halved twice at ages 10 and 15 year approximately.

Spacing is 6 m x 6 m (280 trees/ha) for upright cultivars such as 'Kwai Mai Pink'. More vigorous cultivars such as 'Tai So', 'Souey Tung' and 'Haak Yip' can be planted at 9—12 m between the rows and 6 m between trees (140—185 trees/ha). Orchards need to be thinned out to 70 trees per ha; the density of the closely planted orchards is halved twice at ages 10 and 15 year approximately.

Husbandry

Lychee orchards are normally irrigated except in China. Water is withheld to maintain shoot rest during the 2—3 months before emergence of the inflorescences. During the remainder of the crop cycle moisture stress should be prevented.

Fertilizer applications also should limit trees to a single flush after harvest, maintaining subsequent shoot rest. Thus leaf N should be kept below 1.5—1.8% before panicle emergence. To support floral development and improve fruit retention, fertilizer is applied at panicle emergence and after fruit set. Other times are also mentioned in China and South Africa (before and after harvest). Suggested amounts for well-grown 5-year-old trees are 200 g N, 80 g P and 300 g K per year, increasing to 1000 g N, 300 g P and 1400 g K per year at year 15. Leaf nutrient standards developed for healthy, high-yielding trees in Australia: 1.5—1.8% for N; 0.14—0.22% for P; 0.70—1.10% for K; 0.60—1.00% for Ca; 0.30—0.50% for Mg.

Cincturing has been used commercially in China, Thailand, Australia, Florida and Hawaii to impose shoot rest and improve flowering and fruiting. Trees are cinctured at the completion of the post-harvest flush, if they are healthy and did flush actively.

The general response of lychee trees to any form of pruning is to fill the gaps with vigorous, less fruitful foliage as quickly as possible. Pruning is limited to the first few years to shape the tree. Every 2—3 years older trees are skirted and the interior is thinned after harvest by removing some of the weaker branches completely, to improve structure against wind damage. Clipping the panicles at harvest is a form of pruning too; if too much leaf and wood is removed in the process, flowering in the next year can be reduced.

Fertilizer applications also should limit trees to a single flush after harvest, maintaining subsequent shoot rest. Thus leaf N should be kept below 1.5—1.8% before panicle emergence. To support floral development and improve fruit retention, fertilizer is applied at panicle emergence and after fruit set. Other times are also mentioned in China and South Africa (before and after harvest). Suggested amounts for well-grown 5-year-old trees are 200 g N, 80 g P and 300 g K per year, increasing to 1000 g N, 300 g P and 1400 g K per year at year 15. Leaf nutrient standards developed for healthy, high-yielding trees in Australia: 1.5—1.8% for N; 0.14—0.22% for P; 0.70—1.10% for K; 0.60—1.00% for Ca; 0.30—0.50% for Mg.

Cincturing has been used commercially in China, Thailand, Australia, Florida and Hawaii to impose shoot rest and improve flowering and fruiting. Trees are cinctured at the completion of the post-harvest flush, if they are healthy and did flush actively.

The general response of lychee trees to any form of pruning is to fill the gaps with vigorous, less fruitful foliage as quickly as possible. Pruning is limited to the first few years to shape the tree. Every 2—3 years older trees are skirted and the interior is thinned after harvest by removing some of the weaker branches completely, to improve structure against wind damage. Clipping the panicles at harvest is a form of pruning too; if too much leaf and wood is removed in the process, flowering in the next year can be reduced.

Diseases and Pests

No major disease currently limits lychee growing. A parasitic alga (Cephaleuros sp.) occasionally attacks trees causing loss of vigour. Susceptible cultivars such as 'Souey Tung' and 'Haak Yip' can be protected with two sprays of copper, before and after the wet season. A slow decline and a sudden death have been recorded in southern Queensland, especially on poorly drained soils. Three genera of nematodes (Xiphinema, Paratrichodorus and Helicotylenchus) have been associated with tree decline in Australia. In South Africa post-planting nematicides have shown considerable promise. Basically, the pest complex affecting the crop is the same in different countries. Erinose mite (Eriophyes litchii) is the major pest of the foliage. Severe infestations may damage developing flowers and fruit and kill the growing points. Erinose mite can be very difficult to eradicate; dipping air layers in dimethoate helps prevent the introduction of the mite into orchards. Red-shoulder beetles (Monolepta australis), leaf rolling caterpillars (Platypeplus aprobola and Isotenes miserana) and scales (Chloropulvinaria psidii) occasionally attack lychee trees but can be adequately controlled. Several caterpillars (Phycita leucomilta, Lobesia spp. and Prosotas spp.) attack developing panicles and flowers. One or two sprays of methomyl during the season give effective control. Flowers can also be affected by red-shoulder beetles, thrips and rutherglen bugs. The main insects affecting fruit are fruit spotting bug (Amblypelta nitida and A. lutescens), lychee stink bug (Lyramorpha rosea or Tessaratoma papillosa in China), and a number of moth species, including fruit-piercing moths (e.g. Othreis fullonia) and borers (e.g. Acrocercops glomerella, also found in rambutan and cacao). The bugs cause the loss of young fruit; insecticides provide control. The moths may also cause premature fruit drop, but the deterioration of damaged fruit after harvest is more serious; they cannot all be adequately controlled.

Birds and flying foxes cause serious damage in Australia, Thailand and South Africa in some years.

Birds and flying foxes cause serious damage in Australia, Thailand and South Africa in some years.

Harvesting

Lychees do not ripen off the tree. Maturity is judged by a particular shape, skin colour, skin texture and flavour of each cultivar. A maturity index based on sugar/acid ratio has been developed in Australia. Most fruit can be picked from a tree within 1 week and from a single cultivar in an orchard within 3 weeks. Most growers plant a range of cultivars to spread the picking workload. April to June is the harvest season in northern Thailand. In Bali the fruit is picked around October; in East Kalimantan fruit from forest trees is available in February—March. In most parts of Asia, bunched panicles of fruit are marketed. Standard grades for detached fruits have been developed in Australia.

Yield

Average yields for a 10-year-old tree in southern Queensland range from about 10—50 kg/tree per year in an irregular bearing cultivar such as 'Tai So' to 30—80 kg/tree for a regular bearing cultivar such as 'Wai Chee'. These yields are equivalent to 0.7—11.2 t/ha per year at recommended spacings. Yields of 10 t/ha are attained in well managed orchards in Guangdong, but average yields are only about 2 t/ha per year.

Handling After Harvest

Lychees in Asia are marketed in 22—25 kg bamboo baskets, normally without any refrigeration or post-harvest treatment and consumed within 3 days of picking. Lychees lose their bright red skin and turn brown within a few days after harvest, especially in low humidity. High humidity tends to encourage post-harvest rots. To prevent browning and rotting, Australian growers dip fruit, particularly if not refrigerated on the farm, in 0.5 g benomyl/l solution at 52°C for 2 min. Punnets with PVC covers are used; the film retains sufficient humidity to inhibit browning without condensation clouding the pack. Storage at 5—8°C can prolong shelf life of treated fruit by 4—6 weeks.

Genetic Resources

Most of the world's production is based on Chinese cultivars selected under Chinese conditions. Consequently the genetic diversity of cultivated lychee is narrow. Few attempts have been made to collect material of the 3 subspecies in the wild. Collections of commercial cultivars are held at several places in southern China and also at research institutes in Taiwan, Thailand, India, South Africa, Australia and the United States.

Breeding

Most cultivars are selections from open-pollinated seedlings. The industry in southern Thailand is based on local selections of Chinese cultivars which crop under tropical conditions. However, fruit quality does not match that of the Chinese cultivars. During the last 50 years a few cultivars have been bred in Florida and Hawaii; of these only 'Kaimana' warrants further attention. More recently there have been attempts in Taiwan and Australia to cross-pollinate cultivars with specific characteristics. Most breeding programmes have been limited to small populations of 200—500 plants. Desirable characteristics: regular high yields, large fruit size, bright red skin colour, small seed size, high eating quality, and acceptable ripening and storage. Crosses between the lychee and the longan in the 1920s in China yielded no exceptional fruit.

Prospects

The lychee is an attractive fruit with a strong appeal, traditionally particularly in China, but nowadays also world-wide. Rapid expansion of lychee growing takes place mainly in countries where it is still a minor crop. However, the ultimate increase in production may not be spectacular, as crop failures, caused by deviations from the exacting ecological requirements, dampen the enthusiasm of the growers.

Only when the grower has the means to impose a growth rhythm on the trees that guarantees adequate flowering and more dependable yields, also in years with adverse weather, can a real breakthrough of the crop be expected. Such growing techniques (e.g. better defined application of girdling, water and nutrients) may also widen the scope for lychee within South-East Asia: more localities in east Indonesia could grow cultivars of ssp. chinensis and commercial production of the other subspecies might become feasible.

Only when the grower has the means to impose a growth rhythm on the trees that guarantees adequate flowering and more dependable yields, also in years with adverse weather, can a real breakthrough of the crop be expected. Such growing techniques (e.g. better defined application of girdling, water and nutrients) may also widen the scope for lychee within South-East Asia: more localities in east Indonesia could grow cultivars of ssp. chinensis and commercial production of the other subspecies might become feasible.

Literature

Anonymous, 1985. An album of Guangdong litchi varieties in full colour. Guangdong Province Scientific Technology Commission. 78 pp.

Groff, G.W., 1921. The lychee and longan. Orange Judd Company, New York. 188 pp.

Menzel, C.M., 1983. The control of floral initiation in lychee: a review. Scientia Horticulturae 21: 201—215.

Menzel, C.M., 1984. The pattern and control of reproductive growth in lychee: a review. Scientia Horticulturae 22: 333—345.

Menzel, C.M. & Simpson, D.R., 1986. Description and performance of major lychee cultivars in subtropical Queensland. Queensland Agricultural Journal 112: 125—136.

Menzel, C.M. & Simpson, D.R., 1987. Lychee nutrition: a review. Scientia Horticulturae 31: 195—224.

Menzel, C.M., Watson, B.J. & Simpson, D.R., 1988. The lychee in Australia. Queensland Agricultural Journal 114: 19—27.

Groff, G.W., 1921. The lychee and longan. Orange Judd Company, New York. 188 pp.

Menzel, C.M., 1983. The control of floral initiation in lychee: a review. Scientia Horticulturae 21: 201—215.

Menzel, C.M., 1984. The pattern and control of reproductive growth in lychee: a review. Scientia Horticulturae 22: 333—345.

Menzel, C.M. & Simpson, D.R., 1986. Description and performance of major lychee cultivars in subtropical Queensland. Queensland Agricultural Journal 112: 125—136.

Menzel, C.M. & Simpson, D.R., 1987. Lychee nutrition: a review. Scientia Horticulturae 31: 195—224.

Menzel, C.M., Watson, B.J. & Simpson, D.R., 1988. The lychee in Australia. Queensland Agricultural Journal 114: 19—27.

Author(s)

C.M. Menzel

Correct Citation of this Article

Menzel, C.M., 1991. Litchi chinensis Sonn.. In: Verheij, E.W.M. and Coronel, R.E. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2: Edible fruits and nuts. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.