Record Number

1516

PROSEA Handbook Number

2: Edible fruits and nuts

Taxon

Macadamia integrifolia Maiden & Betche

Protologue

Proc. Linn. Soc. N.S. Wales 21: 64 (1897).

Family

PROTEACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 28

Synonyms

Macadamia ternifolia F. v. Muell. var. integrifolia (Maiden & Betche) Maiden & Betche (1899).

Vernacular Names

Macadamia, Queensland nut, Australian bush nut (En).

Origin and Geographic Distribution

The macadamia is the only commercial food crop indigenous to Australia, originating in the rain forests of south-eastern Queensland and north-eastern New South Wales. The crop was first developed in Hawaii, with trees imported in the 1880s, but not until the 1950s did the Hawaiian success encourage other countries to grow macadamia on a commercial scale.

Close to the equator macadamia is grown commercially in East Africa. In South-East Asia some scattered trees occur, but in northern Thailand trial plantings have been made on a series of promising sites.

Close to the equator macadamia is grown commercially in East Africa. In South-East Asia some scattered trees occur, but in northern Thailand trial plantings have been made on a series of promising sites.

Uses

The fine crunchy texture, rich cream colour and delicate flavour make the macadamia nut one of the finest dessert nuts. The eating quality of the nut is enhanced by lightly roasting in coconut oil and salting. Raw kernels are also popular either alone or in a wide range of confectionery and processed foods. The decomposed husk is commonly used in potting soils.

Production and International Trade

Hawaii dominates the world market, with over 70% of production (20 400 t nuts-in-shell (NIS) from 8100 ha in 1987). Australia supplies 10—15% of world markets (5000 t NIS from 6000 ha) and Costa Rica is similarly poised to commence production on a large scale (500 t from 2000 ha). Production in Africa appears to have levelled off (1700 t NIS from 4250 ha). The United States is the largest market for macadamias and demand is increasing.

Properties

The quality of the kernel is related to its oil content and composition. Nuts are mature when the kernels accumulate 72% or more oil, as determined by specific gravity (SG). Kernels also contain 10% carbohydrates, 9.2% protein which is low in methionine, 0.7% minerals, particularly potassium, and niacin (16.0 mg/kg), thiamine (2.2 mg/kg) and riboflavin (1.2 mg/kg). The characteristic, subtle macadamia flavour is probably due to volatile compounds, the major ones being similar to those in other roasted nuts.

Description

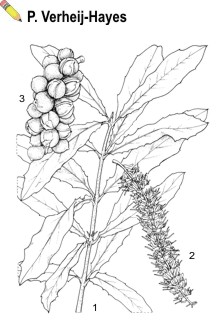

Large spreading tree, attaining a height of 18 m and a spread of 15 m. Leaves in whorls of 3, oblong to oblanceolate, 10—30 cm x 2—4 cm, glabrous, coriaceous, irregularly spiny-dentate when young, in later stages entire; petiole 5—15 mm long; in the axil of each leaf 3 buds are arranged longitudinally, of which usually only the top bud shoots out, making a sharply acute angle with the trunk.

Racemes axillary on mature new growth or on leafless older shoots, pendulous, 10—30 cm long with 100—500 flowers; flowers in groups of 2—4, about 12 mm long, creamy-white; pedicels 3—4 mm long; perianth tubular with 4 petaloid sepals; stamens 4, inserted 2/3 above the base of the tube; pistil about 7 mm long, ovary superior, 1-carpellate with 2 ovules. Fruit a globose follicle, 2.5—4 cm in diameter; pericarp fibrous, ca. 3 mm thick. Seed (nut) mostly 1, globular, with a smooth, hard, thick (2—5 mm) testa enclosing the edible kernel.

Racemes axillary on mature new growth or on leafless older shoots, pendulous, 10—30 cm long with 100—500 flowers; flowers in groups of 2—4, about 12 mm long, creamy-white; pedicels 3—4 mm long; perianth tubular with 4 petaloid sepals; stamens 4, inserted 2/3 above the base of the tube; pistil about 7 mm long, ovary superior, 1-carpellate with 2 ovules. Fruit a globose follicle, 2.5—4 cm in diameter; pericarp fibrous, ca. 3 mm thick. Seed (nut) mostly 1, globular, with a smooth, hard, thick (2—5 mm) testa enclosing the edible kernel.

Image

| Macadamia integrifolia Maiden & Betche - 1, branch with leaves; 2, inflorescence; 3, infructescence |

Growth and Development

Seeds germinate readily and seedling growth, initially slow, gathers momentum as saplings produce a series of extension growth flushes in a year. The juvenile phase lasts for 7 years or more, but grafted trees come into bearing after 3 years.

Floral initiation takes place when temperatures drop and trees become quiescent in autumn, the optimum temperature being 18°C. The initials remain dormant for 50—96 days and the racemes extend after a rise in temperature and some rain. In Australia high yields are associated with a strong and early spring flush prior to anthesis, followed by minimal shoot growth throughout the 6-month nut development period. At the end of that period there is a late summer flush; meanwhile nuts may be retained on the tree for a further 3 months, but gradually they fall.

The flowers are protandrous, the anthers dehiscing 1—2 days before anthesis, whereas the stigma does not support pollen tube growth until 1—2 days after anthesis.

Pollination is by insects; most cultivars are at least partly self-incompatible. Planting pollinator trees and introducing bees are important for good fruit set. Fruitlets continue to be shed up to 2 months after bloom.

Floral initiation takes place when temperatures drop and trees become quiescent in autumn, the optimum temperature being 18°C. The initials remain dormant for 50—96 days and the racemes extend after a rise in temperature and some rain. In Australia high yields are associated with a strong and early spring flush prior to anthesis, followed by minimal shoot growth throughout the 6-month nut development period. At the end of that period there is a late summer flush; meanwhile nuts may be retained on the tree for a further 3 months, but gradually they fall.

The flowers are protandrous, the anthers dehiscing 1—2 days before anthesis, whereas the stigma does not support pollen tube growth until 1—2 days after anthesis.

Pollination is by insects; most cultivars are at least partly self-incompatible. Planting pollinator trees and introducing bees are important for good fruit set. Fruitlets continue to be shed up to 2 months after bloom.

Other Botanical Information

Besides Macadamia integrifolia, Macadamia tetraphylla L.A.S. Johnson also produces edible kernels and is also cultivated. It differs from Macadamia integrifolia by its always spiny leaves, usually occurring in whorls of 4, up to 50 cm long, often sessile (petiole up to 3 mm), pink flowers and a rough-shelled nut. It occupies a more southern area than Macadamia integrifolia. Sterile natural hybrids exist in an overlapping area of distribution in Australia.

Although Macadamia tetraphylla has excellent culinary qualities, its kernel is not favoured by processors because it has a higher residual sugar content which caramelizes on roasting.

Macadamia hildebrandii Steenis is a native species from Sulawesi (Indonesia). [Celebes nut (En), pérandè (Tado), tinapo (Toradja), balo molaba (Tobela)]. Presumably the nuts are edible and the species may be better adapted to a wet tropical climate. Its fruit is indehiscent, but the seed has a thin soft testa.

Although Macadamia tetraphylla has excellent culinary qualities, its kernel is not favoured by processors because it has a higher residual sugar content which caramelizes on roasting.

Macadamia hildebrandii Steenis is a native species from Sulawesi (Indonesia). [Celebes nut (En), pérandè (Tado), tinapo (Toradja), balo molaba (Tobela)]. Presumably the nuts are edible and the species may be better adapted to a wet tropical climate. Its fruit is indehiscent, but the seed has a thin soft testa.

Ecology

The xerophytic characteristics of the macadamia tree, including the sclerophyllous leaves and proteoid roots - dense clusters of rootlets formed to explore poor soils, especially soils low in phosphorus - suggest adaptation to relatively harsh environments. However, the conditions required for optimum production may be quite different from those for survival.

The macadamia occurs naturally in the fringes of subtropical rain forests. It appears to tolerate only a narrow range of temperatures (optimum during the growing season is 25°C) and temperature is the major climatic variable determining growth and productivity. Trees in South-East Asia grow fairly well but flower and fruit sporadically throughout the year. In East Africa, also close to the equator, orchards are planted at elevations of 1000—1600 m, in areas with a prominently seasonal climate, leading to a synchronous resumption of growth and flowering after a cool overcast season. Abnormal tree growth, low yield and poor nut quality have been noted in Africa at higher altitudes with little sunshine during the main season.

The mature macadamia is capable of withstanding mild frosts, but only for short periods. The minimum annual rainfall for macadamias is about 1000 mm, well distributed through the year. The brittle wood makes trees susceptible to wind damage.

Macadamia can be grown in a wide range of soils but not on heavy, impermeable clays and saline or calcareous soils. The trees are most suited to deep, well-drained soils with good organic matter content (ca. 3—4% organic carbon), medium cation exchange capacity and pH of 5.0—6.0.

The macadamia occurs naturally in the fringes of subtropical rain forests. It appears to tolerate only a narrow range of temperatures (optimum during the growing season is 25°C) and temperature is the major climatic variable determining growth and productivity. Trees in South-East Asia grow fairly well but flower and fruit sporadically throughout the year. In East Africa, also close to the equator, orchards are planted at elevations of 1000—1600 m, in areas with a prominently seasonal climate, leading to a synchronous resumption of growth and flowering after a cool overcast season. Abnormal tree growth, low yield and poor nut quality have been noted in Africa at higher altitudes with little sunshine during the main season.

The mature macadamia is capable of withstanding mild frosts, but only for short periods. The minimum annual rainfall for macadamias is about 1000 mm, well distributed through the year. The brittle wood makes trees susceptible to wind damage.

Macadamia can be grown in a wide range of soils but not on heavy, impermeable clays and saline or calcareous soils. The trees are most suited to deep, well-drained soils with good organic matter content (ca. 3—4% organic carbon), medium cation exchange capacity and pH of 5.0—6.0.

Propagation and planting

Early plantings of macadamias were established from seedlings, but these were slow to commence bearing and variable in yield and nut quality. Successful grafting was achieved by using vigorously growing, healthy, recently mature stock and scion material, 1—1.3 cm in diameter and by cincturing scion wood 6—8 weeks before grafting to promote accumulation of carbohydrates. The rootstocks are seedlings 9—12 months old.

The current trend is for high density, hedgerow plantings which maximize early yields. Inter-row spacings of 10 m are most common (7 m if mechanical pruning is carried out). The distance between trees within rows should be 4—5 m, depending on cultivar and growing conditions. Windbreaks should be well established prior to planting.

The current trend is for high density, hedgerow plantings which maximize early yields. Inter-row spacings of 10 m are most common (7 m if mechanical pruning is carried out). The distance between trees within rows should be 4—5 m, depending on cultivar and growing conditions. Windbreaks should be well established prior to planting.

Husbandry

It is preferable for the tree to develop a strong central leader. Corrective pruning will often be required to prevent later limb breakages. Upright cultivars such as 'Kau' (formerly known as selection no 344) and 'Mauka' (741) require less pruning as they are naturally more wind resistant. Mulching is recommended for young trees (when the trees come into bearing it interferes with nut collection). Some weed control measures are generally necessary. Fertilizer management should be guided by leaf and soil analysis, the phenological cycle and yield. Macadamia trees appear to be sensitive to nutrient deficiencies and/or imbalances, and positive responses to N, P, K, Zn, B, S, Mg, Fe, and Cu have been observed.

Diseases and Pests

In their place of origin macadamias are attacked by more than 150 pest species, although parasites and predators usually provide considerable control. Insects which commonly reduce yields include macadamia flower caterpillar (Homoeosoms vagella), fruit spotting bug (Amblypelta nitida), banana spotting bug (Amblypelta lutescens), macadamia nutborer (Cryptophlebia ombrodelta), and macadamia felted coccid (Eriococcus ironsidei). Any of these has the capacity to destroy much of the crop during severe infestations. The macadamia twig-girdler (Neodrepta luteotacetella) and macadamia leafminer (Acrocercops chionosema) destroy foliage and may therefore reduce yield indirectly. Many of the minor macadamia insect pests cause damage sporadically. An integrated pest management system for control, involving monitoring of pest population levels and delaying spraying until action levels are reached is recommended. Rats are particularly fond of macadamia nuts and can be a problem in some areas. In comparison with other fruit trees, relatively few diseases are serious in macadamia.

Harvesting

Nuts fall from the tree naturally in autumn and early winter when they are mature. They are gathered by hand or swept into windrows and picked up by machines; machine harvesting requires a smooth and clean orchard floor.

Yield

Yields of 45 kg nuts-in-shell from better trees or an average of 3.2—3.5 t/ha per year are obtained in Hawaii.

Handling After Harvest

The husk must be removed from the follicle as soon as possible to prevent over-heating, mould development and deterioration in quality. The husked nuts are then dried either artificially in silos or air-dried (10% moisture) on wire racks on the farm. At the factory, nuts are dried to 1—1.5% moisture for longer term storage, most efficient cracking of the shell and more complete recovery of the whole kernels. Drying is done in stages (at 52°C down to 4.5% moisture and then at 77°C down to 1.5% moisture) to avoid adverse effects on kernel quality. The kernels can then be lightly roasted in coconut oil and salted or packaged raw in vacuum-filled foil-laminate bags which prevent development of rancidity. The product is then kept in cold stores. Under these conditions, the kernels can be safely stored for a year.

Genetic Resources

Considerable genetic diversity exists in the range of cultivars and in germplasm collections in Hawaii and Australia. No thorough examination of diversity has been completed in natural populations, which are under threat owing to clearing and poor regeneration through rodent damage.

Breeding

Most commercial cultivars were developed from seedling selection in Hawaii. Of the 120 000 seedlings examined, less than 900 were given Hawaii Agricultural Experiment Station (HAES) accession numbers, 13 were named and 9 of these are planted in substantial numbers. Selection is based on tree characteristics, high yield and superior nut quality.

Prospects

The demand for most tree nuts is good and there is scope for per capita consumption to be increased substantially. The world production of macadamias is increasing steadily but is still less than 1% of world nut production. Production is expected to treble within the next decade. Within South-East Asia only the climates of northern Thailand and eastern Indonesia appear to be sufficiently seasonal to provoke good flowering and fruiting in macadamia, but this needs experimental confirmation.

Literature

Allan, P., 1972. Use of climatic data in predicting macadamia areas. California Macadamia Society Yearbook 18: 77—87.

Cavaletto, C.G., 1983. Macadamia nuts. In: Chan, H.T. Jr (Editor): Handbook of tropical foods. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York. pp. 361—397.

Hamilton, R.A., Ito, P.J. & Chia, C.L., 1983. Macadamia: Hawaii's dessert nut. University of Hawaii Circular No 485. 13 pp.

Ironside, D.A., 1981. Insect pests of macadamia in Queensland. Queensland Department of Primary Industries, Brisbane. 28 pp.

Liang, T., Wong, W.P.H. & Uchara, G., 1983. Simulating and mapping agricultural land productivity: An application to macadamia nut. Agricultural Systems 11: 225—253.

Shigeura, G.T. & Ooka, H., 1984. Macadamia nuts in Hawaii: History and production. University of Hawaii Research and Extension Series 039. 91 pp.

Cavaletto, C.G., 1983. Macadamia nuts. In: Chan, H.T. Jr (Editor): Handbook of tropical foods. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York. pp. 361—397.

Hamilton, R.A., Ito, P.J. & Chia, C.L., 1983. Macadamia: Hawaii's dessert nut. University of Hawaii Circular No 485. 13 pp.

Ironside, D.A., 1981. Insect pests of macadamia in Queensland. Queensland Department of Primary Industries, Brisbane. 28 pp.

Liang, T., Wong, W.P.H. & Uchara, G., 1983. Simulating and mapping agricultural land productivity: An application to macadamia nut. Agricultural Systems 11: 225—253.

Shigeura, G.T. & Ooka, H., 1984. Macadamia nuts in Hawaii: History and production. University of Hawaii Research and Extension Series 039. 91 pp.

Author(s)

R.A. Stephenson & C.W. Winks

Correct Citation of this Article

Stephenson, R.A. & Winks, C.W., 1991. Macadamia integrifolia Maiden & Betche. In: Verheij, E.W.M. and Coronel, R.E. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2: Edible fruits and nuts. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.