Record Number

1525

PROSEA Handbook Number

2: Edible fruits and nuts

Taxon

Manilkara zapota (L.) P. van Royen

Protologue

Blumea 7: 410 (1953).

Family

SAPOTACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 26

Synonyms

Achras zapota L. (1753), p.p., Pouteria mammosa (L.) Cronquist (1946), p.p. min., Nispero achras (Miller) Aubréville (1965), nom. inval.

Vernacular Names

Sapodilla, naseberry (En). Sapotillier (Fr). Indonesia: sawo manila, ciku (Sundanese), sawo londo (Java). Malaysia: ciku. Philippines: chico. Cambodia: lomut. Laos: lamud. Thailand: lamut, lamut-farang. Vietnam: xabôchê, hông xiêm, tâ lu'c.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Sapodilla is a native of Central America, Mexico and the West Indies. It is now cultivated to a greater or lesser extent in the tropical lowlands of both hemispheres. It is an important fruit all over South-East Asia.

Uses

Sapodilla is grown mainly for its fruit which is predominantly eaten fresh. The fruits may also be used in sherbets or ice cream or made into preserve, butter or jam. The juice may be boiled into syrup or fermented into wine or vinegar. Wild and cultivated trees in America are tapped for their milky latex which coagulates into chicle, the principal constituent of chewing gum before the advent of synthetics. This gum is also used in the manufacture of transmission belts, in dental surgery, and as a substitute for gutta percha, a coagulum of the latex of Palaquium spp., also in the Sapotaceae, which had many applications in industry before the advent of plastics.

The wood is an excellent material for making cabinets and furniture. The seeds are antipyretic. In Indonesia the flowers are used as one of the ingredients in preparing a powder which is rubbed on the body of a woman after childbirth. The tannin from the bark is used to tan ship sails and fishing tackle; in Cambodia the tannin is used to cure diarrhoea and fever.

The wood is an excellent material for making cabinets and furniture. The seeds are antipyretic. In Indonesia the flowers are used as one of the ingredients in preparing a powder which is rubbed on the body of a woman after childbirth. The tannin from the bark is used to tan ship sails and fishing tackle; in Cambodia the tannin is used to cure diarrhoea and fever.

Production and International Trade

Sapodilla is popular in South-East Asia because the fruit is very sweet. Statistics indicate that the region is the major producer of the fruit: in 1987 Thailand produced 53 650 t with a total area of 18 950 ha; the Philippines 11 900 t with 4780 ha, Peninsular Malaysia 15 000 t with 1000 ha; in Indonesia production during 1986 was estimated at 54 800 t. The fruit is consumed almost entirely in the country of production and international trade is negligible. In many areas it is available when few other fruits are in season.

Properties

The sapodilla fruit is rather dry and some cultivars have a gritty texture. About 84% of the fruit is edible and contains, per 100 g: water 74 g, protein 0.5 g, fat 0.9 g, carbohydrates 24 g, fibre 3.0 g, ash 0.4 g, phosphorus 32 g, calcium 9 mg, iron 1 mg, sodium 5 mg, potassium 198 mg, vitamin A 85 IU, thiamine and riboflavin 0.01 mg, niacin 0.3 mg and vitamin C 26 mg. The energy value is 400 kJ/100 g. The predominant organic acid in the fruit is malic acid.

Description

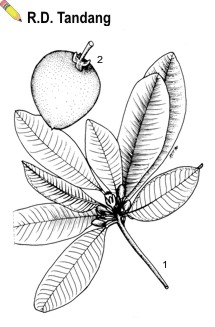

Evergreen, upright to spreading tree, 5—20(—30)m tall, all parts rich in white gummy latex; trunk low-branched, bark rough, dark-brown, crown globose or pyramidal, conforming to Aubréville's architectural model. Leaves alternate, ovate-elliptic to oblong-lanceolate, 3.5—15 cm x 1.5—7 cm, cuneate or obtusely acuminate at both ends, frequently emarginate, entire, glabrescent, glossy dark green, midrib prominent below, lateral nerves numerous, parallel; petiole 1—3.5 cm long. Flowers solitary in upper leaf axils, usually pendulous, up to 1.5 cm in diameter, brown-hairy outside; pedicel 1—2 cm long; calyx deeply 6-parted, usually in two whorls, densely grey or brown tomentose outside; corolla white, campanulate, 6 lobes about half as long as the tube; staminodes 6, petaloid; stamens 6; ovary 10—12-celled, villous; style subulate, exserted from the flower. Fruit a pendulous berry, globose, ovoid or ellipsoid, 3—8 cm x 3—6 cm, rounded or impressed at base, apex rounded and crowned by the remnants of the style; skin thin, dull reddish to yellow-brown, covered with a sandy brown scurf; flesh juicy, soft, yellow to red-brown, sweet. Seeds 0—6(—12), oblong, 2 cm long, brown or black, compressed laterally, hilum distinct.

Image

| Manilkara zapota (L.) P. van Royen - 1, flowering branch; 2, fruit |

Growth and Development

The seeds germinate about 30 days after sowing without any treatment and exhibit an epigeal type of germination. The seedlings grow very slowly, producing a central stem which dominates the whorls of laterals in trees with an upright habit; the spreading habit is achieved by more prominent sympodial extension of the laterals. In an equable climate some extending shoots can be found at any time, but trees relieved from stress may seem to produce a general flush. Seedling trees start to flower 6—10 or more years after planting; grafted trees in 4—6 years and marcotted trees in 3—4 years. Flowers are produced in the leaf axils near the tip of young or mature shoots. These shoot tips have greatly shortened internodes, so that the flowers appear to be borne in clusters. Flowering may take place throughout the year but the peak of flowering in the Philippines is April to June, that is early in the rainy season.

Observation of 2 cultivars in the Philippines showed that flower buds reach anthesis 45—60 days after emergence. The stigma is receptive between one day before and 3 days after flower opening; on the day of opening it is sticky with stigmatic fluid. Self-fertile cultivars produce much pollen, which is viable. Cross-pollination by insects, e.g. bees, is recommended and is necessary for low-yield cultivars, most of which produce little pollen, which is defective. Fruit growth as observed in India proceeds in 3 distinct stages: in the first 16 weeks diameter exceeds length; after a transitory period of 4 weeks the fruit assumes its characteristic oblong-ovoid shape and takes another 9 weeks to ripen. The fruits take about 6—8.5 months to mature so that in the Philippines the main harvest season is from December to February. In Thailand the fruit is more seasonal and abundant from September to December.

Observation of 2 cultivars in the Philippines showed that flower buds reach anthesis 45—60 days after emergence. The stigma is receptive between one day before and 3 days after flower opening; on the day of opening it is sticky with stigmatic fluid. Self-fertile cultivars produce much pollen, which is viable. Cross-pollination by insects, e.g. bees, is recommended and is necessary for low-yield cultivars, most of which produce little pollen, which is defective. Fruit growth as observed in India proceeds in 3 distinct stages: in the first 16 weeks diameter exceeds length; after a transitory period of 4 weeks the fruit assumes its characteristic oblong-ovoid shape and takes another 9 weeks to ripen. The fruits take about 6—8.5 months to mature so that in the Philippines the main harvest season is from December to February. In Thailand the fruit is more seasonal and abundant from September to December.

Other Botanical Information

For a discussion of the correct scientific name of the sapodilla see Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H.E. Moore & Stearn. Numerous cultivars exist, often bearing local names; in many cases names in different localities are presumably synonyms.

In Indonesia 2 groups of cultivars are distinguished: Sawo manila with ovoid fruit, including 'Sawo Betawi' and 'Sawo Kulan' and Sawo apel with globose fruits, e.g. 'Sawo Apel Benar' and 'Sawo Apel Lilin'.

In the Philippines the small-fruited, prolific 'Pineras' is most common. 'Ponderosa' has large fruit of excellent quality but it does not soften uniformly after harvest and trees require cross-pollination for good yield. Other cultivars are 'Sao Manila' and 'Gonzalez'. Well-known Thai cultivars are the small-fruited 'Krasuey', the fairly large-fruited 'Kai Hahn' and the medium sized, globose 'Makok'. Popular cultivars in Malaysia are 'Santong', 'C 54' and 'C 58'. In Queensland, Australia, cultivars from various countries have been evaluated; the most promising cultivars are 'Kai Hahn', 'Makok', 'C 58', 'Tropical', 'BKD 110' and 'Sao Manila'.

In Indonesia 2 groups of cultivars are distinguished: Sawo manila with ovoid fruit, including 'Sawo Betawi' and 'Sawo Kulan' and Sawo apel with globose fruits, e.g. 'Sawo Apel Benar' and 'Sawo Apel Lilin'.

In the Philippines the small-fruited, prolific 'Pineras' is most common. 'Ponderosa' has large fruit of excellent quality but it does not soften uniformly after harvest and trees require cross-pollination for good yield. Other cultivars are 'Sao Manila' and 'Gonzalez'. Well-known Thai cultivars are the small-fruited 'Krasuey', the fairly large-fruited 'Kai Hahn' and the medium sized, globose 'Makok'. Popular cultivars in Malaysia are 'Santong', 'C 54' and 'C 58'. In Queensland, Australia, cultivars from various countries have been evaluated; the most promising cultivars are 'Kai Hahn', 'Makok', 'C 58', 'Tropical', 'BKD 110' and 'Sao Manila'.

Ecology

Sapodilla is a very adaptable species. It thrives in the tropics, but is found in large numbers at elevations up to 2500 m in Ecuador and also in the subtropics (Israel); mature trees are not greatly damaged by a few degrees of frost. Sapodilla is very drought-resistant, doing well in the taxing monsoon climates of India. With its tough branches the tree tolerates strong winds and salt sprays close to the seashore. However, growth and fruit quality are impaired in extreme environments; the tree thrives in warm, moist tropical lowlands, usually below 600 m in South-East Asia. The best soil for sapodilla is a rich, well drained, sandy loam, but few soils are unsuitable and sapodilla comes second after the date palm in the category of fruit trees with high tolerance of saline soils.

Propagation and planting

Cultivars are propagated either by grafting or marcotting. The seeds for rootstocks are sown in a sandy seedbed, about 2 cm apart and at a depth of about 1 cm. The seeds germinate in about 30 days, fresh seed giving up to about 80% germination. Seeds can be kept for several months but it is best to sow them immediately after collection. After a few months the seedlings are transplanted into polybags. They grow very slowly; even if spurred on by nitrogen applications, it takes 2—3 years before the rootstocks are ready for grafting.

Other species of Manilkara Adans. have been tried as rootstocks, partly to find faster growing seedlings. Manilkara kauki (L.) Dubard did well in Indonesia and India and is being tried in the Philippines. However, in India Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard proved to be the best rootstock, even after 40 years, provided only the more vigorous seedlings were grafted, there being much variation in vigour. Some species of Madhuca J.F. Gmelin, Palaquium Blanco and Sideroxylon L. are also graft-compatible with sapodilla. Inarching is the traditional grafting method, giving as much as 95—100% success. However it is a rather laborious method. In the Philippines it has been replaced by cleft or wedge grafting. Sapodilla can be grafted any month of the year, but best results are obtained during the cooler and drier months (November—February in the Philippines). Scions are cut from quiescent terminal shoots with buds ready to sprout. Fruiting twigs are better than non-fruiting twigs. Cleft grafting gives 80—90% success.

Marcotting is best done during the rainy season. The branches to be used should be more or less upright and have a diameter of about 1 cm. Coconut coir is one of the common rooting materials used. Treating the girdled stem with a root hormone is beneficial. Complete rooting is achieved in 4—12 months depending on the size of the branch and on the cultivar used. Success in marcotting is 60% or more, the smaller branches generally showing the highest percentage take. Mist propagation using leafy stem cuttings treated with a root-promoting substance has been successful. The suggested tree spacing in the orchard is 6—10 m. Planting is best done at the onset of the rainy season.

Other species of Manilkara Adans. have been tried as rootstocks, partly to find faster growing seedlings. Manilkara kauki (L.) Dubard did well in Indonesia and India and is being tried in the Philippines. However, in India Manilkara hexandra (Roxb.) Dubard proved to be the best rootstock, even after 40 years, provided only the more vigorous seedlings were grafted, there being much variation in vigour. Some species of Madhuca J.F. Gmelin, Palaquium Blanco and Sideroxylon L. are also graft-compatible with sapodilla. Inarching is the traditional grafting method, giving as much as 95—100% success. However it is a rather laborious method. In the Philippines it has been replaced by cleft or wedge grafting. Sapodilla can be grafted any month of the year, but best results are obtained during the cooler and drier months (November—February in the Philippines). Scions are cut from quiescent terminal shoots with buds ready to sprout. Fruiting twigs are better than non-fruiting twigs. Cleft grafting gives 80—90% success.

Marcotting is best done during the rainy season. The branches to be used should be more or less upright and have a diameter of about 1 cm. Coconut coir is one of the common rooting materials used. Treating the girdled stem with a root hormone is beneficial. Complete rooting is achieved in 4—12 months depending on the size of the branch and on the cultivar used. Success in marcotting is 60% or more, the smaller branches generally showing the highest percentage take. Mist propagation using leafy stem cuttings treated with a root-promoting substance has been successful. The suggested tree spacing in the orchard is 6—10 m. Planting is best done at the onset of the rainy season.

Husbandry

Newly planted trees need to be watered during dry periods to improve establishment. Moreover, the trees respond by extra growth and come into bearing more quickly. Although the trees are very drought-resistant, flowers and fruitlets are shed under moisture stress; hence in dry climates bearing trees also benefit from irrigation.

The tree architecture with a central leader and whorls of laterals extending sympodially, calls for little pruning, the more so since the flowers are borne near the shoot tip. However, in clonally propagated trees the architecture is not so clearly expressed. In cultivars with upright growth the central leader may be headed back in the formative years to promote lateral growth. In cultivars with a cluttered habit pseudo-central-leaders should be removed and some thinning of weak and interlacing branches is recommended as the trees grow older. Also the lower whorl of branches is removed as it sags towards the ground.

In experiments in India the response of both growth and fruiting to nitrogen was quite convincing. Mature trees need 1.5 kg N or more per year, recommended doses of P2O5 and K2O are about 0.5 kg per tree. Fertilizer or manure is applied at the onset of the rainy season, in time to support the increased extension growth and flowering brought on by the rains, and well before the end of the rainy season to sustain fruit growth. In this way fertilizing may further concentrate the crop in a certain period. Fertilizer is applied in a ring under the dripline of the tree canopy.

The tree architecture with a central leader and whorls of laterals extending sympodially, calls for little pruning, the more so since the flowers are borne near the shoot tip. However, in clonally propagated trees the architecture is not so clearly expressed. In cultivars with upright growth the central leader may be headed back in the formative years to promote lateral growth. In cultivars with a cluttered habit pseudo-central-leaders should be removed and some thinning of weak and interlacing branches is recommended as the trees grow older. Also the lower whorl of branches is removed as it sags towards the ground.

In experiments in India the response of both growth and fruiting to nitrogen was quite convincing. Mature trees need 1.5 kg N or more per year, recommended doses of P2O5 and K2O are about 0.5 kg per tree. Fertilizer or manure is applied at the onset of the rainy season, in time to support the increased extension growth and flowering brought on by the rains, and well before the end of the rainy season to sustain fruit growth. In this way fertilizing may further concentrate the crop in a certain period. Fertilizer is applied in a ring under the dripline of the tree canopy.

Diseases and Pests

There are no serious diseases of the sapodilla. The pink disease (Corticium salmonicolor) is a canker which kills affected branches. In India, a leaf spot disease (Phaeophleospora indica) has been reported.

Some insect pests may inflict serious damage to the sapodilla trees. The maggots of the oriental fruit fly (Dacus dorsalis) feed on the flesh of ripe fruit making it unfit for consumption. The larvae of the phycitid fruit borer (Alophia sp.) attack the fruits at all stages of development. The larvae of the gelechiid moth (Eustalodes anthivora) feed on the flowers causing them to drop. The twig-borer (Niponoclea albata and N. capito) larvae tunnel into the twigs and pupate inside, whereas the adult beetles girdle the branches. Mealy bugs and aphids feed on the leaves, young shoots, flowers and young fruits. Scale insects cluster around the twigs and branches and along the leaf midribs, causing leaf drop and twig dieback.

Some insect pests may inflict serious damage to the sapodilla trees. The maggots of the oriental fruit fly (Dacus dorsalis) feed on the flesh of ripe fruit making it unfit for consumption. The larvae of the phycitid fruit borer (Alophia sp.) attack the fruits at all stages of development. The larvae of the gelechiid moth (Eustalodes anthivora) feed on the flowers causing them to drop. The twig-borer (Niponoclea albata and N. capito) larvae tunnel into the twigs and pupate inside, whereas the adult beetles girdle the branches. Mealy bugs and aphids feed on the leaves, young shoots, flowers and young fruits. Scale insects cluster around the twigs and branches and along the leaf midribs, causing leaf drop and twig dieback.

Harvesting

Some fruit may be ripening on the tree throughout the year, but generally there are one or two major harvest peaks because of concentrated blossoming, or because viable pollen is produced during certain periods. The fruit is climacteric and is picked when mature but still firm; it needs a few days to soften and become edible. The fruits are considered mature when the skin colour turns from green to yellowish-brown, the scurfy bloom on the skin comes off easily and the latex flow is minimal when the fruit is detached. This change is not easily seen, however, because the fruit surface is covered with a brown powdery material. Therefore the surface of a few fruits is rubbed with the thumb to remove the bloom and to observe the skin colour; as a final test these fruits may be detached. Mature fruits are picked without the stalk. A white latex exudes from the stalk, and the practice in the Philippines is to put the fruits in a container with water and allow them to 'bleed'. Bleeding is stimulated by scraping the stalk end with the thumb nail or with a sharp object. If this is not done the latex remains inside the fruit and coagulates there. The fruits are scrubbed with a piece of cloth to remove the bloom and allowed to dry by placing them with their stalk ends down.

Yield

There are few records of actual yields. In India, a norm for annual fruit number for trees of 7 years and older is to multiply tree age by 100, 2500 fruits being considered the maximum. Although the average yields calculated on the basis of area and production are low (except for Peninsular Malaysia), sapodilla is certainly not a reluctant bearer. Annual yields per ha of 20—30 t have been reported in Florida, 20—25 t in the Philippines and 20—80 t in India.

Handling After Harvest

The fruits are usually graded and marketed immediately after harvest. They ripen in 3—7 days. The fruits can be stored at low temperature to prolong their shelf life. Unripe fruits stored at 15°C can be kept in good condition for about 17 days; at lower temperatures unripe fruits stored for more than 10 days do not ripen normally. Ripe fruits stored at 0°C remain in good condition for 12—13 days.

Genetic Resources

Seedling trees exhibit much variation in plant and fruit characters. In the Philippines, for example, the introduction of new cultivars and the planting of their seedlings has led to wide variability in the sapodilla population. Moreover, many seedlings never bear fruit, pollen sterility being quite common in seedling populations. In recent years germplasm has been collected by the Institute of Plant Breeding in Los Baños, the Philippines; Australia (Queensland), India, Cuba, Brazil, Costa Rica, the United States (Florida, Puerto Rico, Hawaii) and some other countries also maintain sapodilla germplasm collections.

Breeding

Cultivars result from clonal propagation of selected seedling trees. The major objectives in varietal improvement are large fruit size, good eating quality and seedless fruits. Controlled hybridization started in India in the 1950s, but this has not yet resulted in the introduction of new cultivars. Only a few parents (e.g. 'Prolific' from Florida) produce seedling offspring with viable pollen, bearing regularly.

Prospects

The sapodilla is a very popular fruit in South-East Asia and other tropical countries. It would seem that supplies do not fully meet domestic demand. Trees are sufficiently fruitful and manageable to be grown in orchards. The factors that largely determine the scope for expansion of commercial production are shortening of the nursery period, better insight into pollen viability and the compatibility of cultivars, as well as development of growing techniques to shift the main flowering and harvesting seasons.

Literature

Clarke, F.F.G., 1954. Eustalodes anthivora (Gelechiidae, Lepidoptera), a new pest of Achras zapota in the Philippines. The Philippine Agriculturists 37: 450—454.

Coronel, R.E., 1966. That chico called Ponderosa. Agriculture at Los Baños 5: 1—3.

De Peralta, E. & de la Cruz, E.J., 1954. Preliminary study on the vegetative propagation of the chico. Araneta Journal of Agriculture 2: 25—32.

Gonzalez, L.G. & Fabella, E.L., 1952. Intergeneric graft-affinity of the chico. The Philippine Agriculturists 35: 402—407.

Gonzalez, L.G. & Feliciano. Jr., P.A., 1953. The blooming and fruiting habits of the Ponderosa chico. The Philippine Agriculturists 37: 384—398.

Moncur, W.M., 1988. Floral development of tropical and subtropical fruit and nut species. An atlas of scanning election micrographs. Natural Resources Series No 8. Division Water and Land Resources, CSIRO, Melbourne. pp. 171—174.

Moore, H.E. & Stearn, W.T., 1967. The identity of Achras zapota L. and the names for the sapodilla and the sapote. Taxon 16: 382—395.

Schroeder, C.A., 1958. The origin, spread and improvement of the avocado, sapodilla and papaya. Indian Journal of Horticulture 15: 116—128.

Coronel, R.E., 1966. That chico called Ponderosa. Agriculture at Los Baños 5: 1—3.

De Peralta, E. & de la Cruz, E.J., 1954. Preliminary study on the vegetative propagation of the chico. Araneta Journal of Agriculture 2: 25—32.

Gonzalez, L.G. & Fabella, E.L., 1952. Intergeneric graft-affinity of the chico. The Philippine Agriculturists 35: 402—407.

Gonzalez, L.G. & Feliciano. Jr., P.A., 1953. The blooming and fruiting habits of the Ponderosa chico. The Philippine Agriculturists 37: 384—398.

Moncur, W.M., 1988. Floral development of tropical and subtropical fruit and nut species. An atlas of scanning election micrographs. Natural Resources Series No 8. Division Water and Land Resources, CSIRO, Melbourne. pp. 171—174.

Moore, H.E. & Stearn, W.T., 1967. The identity of Achras zapota L. and the names for the sapodilla and the sapote. Taxon 16: 382—395.

Schroeder, C.A., 1958. The origin, spread and improvement of the avocado, sapodilla and papaya. Indian Journal of Horticulture 15: 116—128.

Author(s)

R.E. Coronel

Correct Citation of this Article

Coronel, R.E., 1991. Manilkara zapota (L.) P. van Royen. In: Verheij, E.W.M. and Coronel, R.E. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2: Edible fruits and nuts. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.