Record Number

1538

PROSEA Handbook Number

2: Edible fruits and nuts

Taxon

Psidium guajava L.

Protologue

Sp. Pl.: 470 (1753).

Family

MYRTACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 22

Synonyms

Psidium aromaticum Blanco (1837).

Vernacular Names

Guava (En). Goyavier (Fr). Brunei: jambu batu (Malay), biyabas. Indonesia: jambu biji (Malay), jambu klutuk (Javanese). Malaysia: jambu biji, jambu kampuchia, jambu berase (north). Philippines: guava, bayabas (Tagalog), guyabas (Iloko). Burma: malakapen. Cambodia: trapaek sruk. Laos: si da. Thailand: farang (central), ma-kuai, ma-man (north). Vietnam: oi.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Guava is indigenous to the American tropics. In the opinion of De Candolle it originates from the area between Mexico and Peru. The Spaniards took it across the Pacific to the Philippines and the Portuguese introduced it from the West to India. At present it is well distributed and naturalized throughout the tropics and subtropics.

Uses

The fruit is usually eaten raw, both green and ripe (when it becomes fragrant). It is also stewed and used in shortcakes and pies. After removing the seeds, the pulp is made into preserves, jam, jelly, juice and nectar. Well-made guava jelly is deep wine-coloured, clear, of very firm consistency, and retains something of the pungent musky flavour of the fresh fruit. Guava paste or guava cheese as known in the West Indies is made by evaporating the pulp with sugar; it is eaten as a sweetmeat. A firm in the Philippines dehydrates slices of the outer, non-seeded part of the fruit to make a similar product. The fruit, peeled, halved and cooked in light syrup, is canned and the juice and nectar are also preserved in this way. Guava powder is a good source of vitamin C and pectin. In some Asian countries such as Indonesia, the leaves are used in cooking, and medicinally against diarrhoea; they can also be used for dyeing and tanning.

The wood is moderately strong and durable indoors; it is used for handles and in carpentry and turnery.

The wood is moderately strong and durable indoors; it is used for handles and in carpentry and turnery.

Production and International Trade

Because of its ease of culture, high nutritional value of the fruit and popularity of the processed products, guava is important in international trade as well as in the local markets of over 60 (sub)tropical countries. The largest producers are countries in Central and South America (Brazil, Mexico), India and Thailand (100 000 t in 1981/82). Mean production in Java in 1981 and 1982 was 56 000 t. Statistical information is hard to get because in most countries a large part of the crop comes from home gardens. International trade is virtually limited to processed products and includes exports to the United States, Japan and Europe.

Properties

In good cultivars nearly the entire fruit is edible. Per 100 g edible portion the fruit contains: water 83.3 g, protein 1 g, fat 0.4 g, carbohydrates 6.8 g, fibre 3.8 g, ash 0.7 g, vitamin C 337 mg. The energy value per 100 g is 150—210 kJ.

The level of vitamin C in guava varies widely (10—2000 mg/100 g fruit), depending on the cultivar, environment and tree management. The skin and firm flesh contain the most vitamin C. The content reaches a maximum in green fully mature fruit and declines rapidly as the fruit ripens. Guavas are also a rich source of pectin (range 0.1—1.8%). Pectin content increases during ripening and declines rapidly in over-ripe fruit.

The level of vitamin C in guava varies widely (10—2000 mg/100 g fruit), depending on the cultivar, environment and tree management. The skin and firm flesh contain the most vitamin C. The content reaches a maximum in green fully mature fruit and declines rapidly as the fruit ripens. Guavas are also a rich source of pectin (range 0.1—1.8%). Pectin content increases during ripening and declines rapidly in over-ripe fruit.

Description

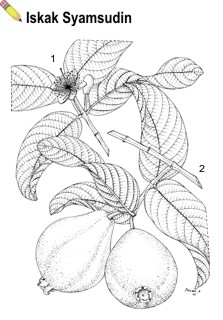

Shallow-rooted shrub or small tree, up to 10 m tall, branching from the base and often producing suckers. Bark smooth, green to red-brown, peeling off in thin flakes. Young twigs 4-angled and ridged, pubescent. Leaves opposite, glandular; petiole 3—10 mm long; blade elliptical to oblong, 5—15 cm x 3—7 cm, glabrous above, finely pubescent beneath, veins prominent below. Flowers solitary or in 2—3-flowered cymes, axillary, ca. 3 cm in diameter; calyx lobes 4—6, 1—1.5 cm long, irregular, persistent; petals 4—5, white, 1—2 cm long; stamens numerous, 1—2 cm long; ovary 4—5-locular; style 1.5—2 cm long, stigma capitate. Fruit a berry, globose, ovoid or pyriform, 4—12 cm long, surmounted by the calyx lobes; exocarp green to yellow; mesocarp fleshy, white, yellow, pink or red, with stone cells, sour to sweet and aromatic. Seeds usually numerous, embedded in pulp, yellowish, bony, reniform, 3—5 mm long.

Image

| Psidium guajava L. - 1, flowering branch; 2, fruiting branch |

Growth and Development

Guava seeds retain their viability for about a year at 8°C and low humidity. One of the most critical botanical characteristics of guava is that flowers are borne on newly emerging lateral shoots, irrespective of the time of the year. Consequently the occurrence of bloom and fruiting in the course of the year can be very erratic or perfectly seasonal, depending on how the environment affects shoot growth. This characteristic allows the tree to be manipulated to crop when desired in a favourable tropical climate. Defoliation and/or pruning are the main methods to force the axillary buds to shoot. Presumably the flowers are already differentiated before the side shoots emerge, implying that the lateral buds should not be forced to break before differentiation has been completed. Shoot growth is indeterminate; under good growing conditions long vigorous shoots dominate, which suppress the emergence of flowering side shoots.

A load of fruit acts as a strong enough sink to moderate extension growth and to delay the leafing out of lateral buds until after harvest. Good fruiting is therefore instrumental in establishing the desired pattern of shoot growth.

The pollen is viable for up to 42 h and the stigmas are receptive for about 2 days. Bees are the principal pollinators. There is some self- and cross-incompatibility but several cultivars set fair crops of seedless or few-seeded fruit. It is not known to what extent erratic flowering through the year affects the pollination intensity.

Seedlings may flower within 2 years; clonally propagated trees often begin to bear during the first year after planting. The trees reach full bearing after 5—8 years, depending on growing conditions and spacing. The guava is not a long-lived tree (about 40 years), but the plants may bear heavily for 15 to 25 years.

A load of fruit acts as a strong enough sink to moderate extension growth and to delay the leafing out of lateral buds until after harvest. Good fruiting is therefore instrumental in establishing the desired pattern of shoot growth.

The pollen is viable for up to 42 h and the stigmas are receptive for about 2 days. Bees are the principal pollinators. There is some self- and cross-incompatibility but several cultivars set fair crops of seedless or few-seeded fruit. It is not known to what extent erratic flowering through the year affects the pollination intensity.

Seedlings may flower within 2 years; clonally propagated trees often begin to bear during the first year after planting. The trees reach full bearing after 5—8 years, depending on growing conditions and spacing. The guava is not a long-lived tree (about 40 years), but the plants may bear heavily for 15 to 25 years.

Other Botanical Information

Polyploidy is not uncommon in guava; parthenocarpy occurs in some diploid as well as triploid cultivars.

The species shows great diversity in tree size, yield and fruit quality. Some wild seedlings produce very small seedy, gritty, musky fruit, whereas selected types can produce large, almost seedless, smooth-textured fruit with pleasant flesh (red or pink) and high flesh recovery. Dessert types have lower acidity and many are white- or yellow-fleshed. There are numerous cultivars. Dual purpose types, which are a compromise between dessert and processing requirements, have been developed in Hawaii and South Africa. In South-East Asia fresh-fruit cultivars predominate. They are generally large-fruited and sweet, most have white (e.g. 'Glohmsahlee' in Thailand) or light yellow flesh.

The species shows great diversity in tree size, yield and fruit quality. Some wild seedlings produce very small seedy, gritty, musky fruit, whereas selected types can produce large, almost seedless, smooth-textured fruit with pleasant flesh (red or pink) and high flesh recovery. Dessert types have lower acidity and many are white- or yellow-fleshed. There are numerous cultivars. Dual purpose types, which are a compromise between dessert and processing requirements, have been developed in Hawaii and South Africa. In South-East Asia fresh-fruit cultivars predominate. They are generally large-fruited and sweet, most have white (e.g. 'Glohmsahlee' in Thailand) or light yellow flesh.

Ecology

The guava is a hardy tree that adapts to a wide range of growing conditions. In the tropics the tree is found from sea level to an altitude of about 1500 m. Guava can stand temperatures from 15—45°C; the highest yields are recorded at mean temperatures of 23—28°C. In the subtropics quiescent trees withstand light frosts and 3.5—6 months (depending on the cultivar) of mean temperatures above 16°C suffice for flowering and fruiting. Guava is more drought-resistant than most tropical fruit crops. For maximum production in the tropics, however, it requires 1000—2000 mm of rain, evenly distributed over the year. If fruit ripens during a very wet period it loses flavour and may split.

Propagation and planting

Guavas grown for processing may be propagated by seed; about 70% of seedlings retain the general characteristics of the parent tree. The seed germinates well, within 15—20 days from sowing and the seed remains viable for a long time. Seedlings are pricked out and transferred to nursery rows or pots to be raised further until they are ready for planting in the field (after 6—12 months) or to be budded.

Guavas grown for their fresh fruit are clonally propagated. In South-East Asia this is usually done through air layering, but for larger numbers, shield or patch budding onto seedling rootstocks is recommended. Success depends on vigorous growth of both mother tree and rootstock. Budwood should be mature (bark no longer green) and the leaves are cut 2 weeks before budding to allow the buds to swell. Budding is best done as soon as the rootstock is thick enough to take the bud; in old stocks the buds do not sprout readily. Trees are ready for field planting after 4—5 months.

Other propagation methods, e.g. using cuttings or grafting, can also be employed. Micro-propagation using nodal explants from mother trees has been reported from India with 70% success in transplantation.

For intensively managed orchards in Thailand (frequent pruning, continuous cropping) trees are spaced only 4—6 m apart, but seedlings for fruit processing may be spaced up to 10 m x 8 m.

Guavas grown for their fresh fruit are clonally propagated. In South-East Asia this is usually done through air layering, but for larger numbers, shield or patch budding onto seedling rootstocks is recommended. Success depends on vigorous growth of both mother tree and rootstock. Budwood should be mature (bark no longer green) and the leaves are cut 2 weeks before budding to allow the buds to swell. Budding is best done as soon as the rootstock is thick enough to take the bud; in old stocks the buds do not sprout readily. Trees are ready for field planting after 4—5 months.

Other propagation methods, e.g. using cuttings or grafting, can also be employed. Micro-propagation using nodal explants from mother trees has been reported from India with 70% success in transplantation.

For intensively managed orchards in Thailand (frequent pruning, continuous cropping) trees are spaced only 4—6 m apart, but seedlings for fruit processing may be spaced up to 10 m x 8 m.

Husbandry

Since flowering takes place on newly emerging shoots, the fruiting pattern follows the flushing pattern. Under minimal husbandry in the tropics this often means that there is a major harvest and a minor second crop, corresponding to a major and a minor flush.

Husbandry may be aimed at maximizing the main crop and establishing a crop cycle of less than one year. To do this the trees are pruned and defoliated shortly after harvest, to generate a general flush which bears the flowers for the next crop. As the time from flowering to harvest is 14—20 weeks, depending on the cultivar, a crop cycle takes 7—9 months. The other husbandry techniques, such as fertilizing, etc. are timed in a way corresponding to the subtropics where there is naturally a single crop over a one-year cycle. In Thailand, irrigation during the dry season and frequent light pruning to promote the emergence of flowering shoots are employed for continuity of production throughout the year. Where the crop is cycled most fertilizer is applied as a basal dressing at the end of the harvest, if necessary supplemented by a top dressing. If the trees are cropped continuously, fertilizers are applied in several small doses. Minimal foliar nutrient levels are approximately: N 1.65%, P 0.26%, K 1.4%, Ca 1.25% and Mg 0.3%.

In young vigorously growing trees the leading branches can be bent down and tipped to promote sprouting of laterals. At the start of subsequent cycles some of the vigorous branches are cut out to maintain an open tree structure. If the trees bear well the wood ages quickly, so that in mature trees the emphasis is on replacement pruning: cutting back sagging branches to a young twig. In this way tree height and spread are restricted, so that trees can be spaced closely and no ladders are needed (Thailand).

Thinning is necessary for fresh market fruit. Lateral shoots usually bear 2—6 flowers of which only 1 or 2 fruits should remain. In Thailand the fruit is bagged after thinning. This enhances fruit quality and protects against fruit flies. However, since polythene bags are used in which the water vapour condenses, the fruit has to be harvested green to prevent rot. In the Philippines paper bags are used.

Husbandry may be aimed at maximizing the main crop and establishing a crop cycle of less than one year. To do this the trees are pruned and defoliated shortly after harvest, to generate a general flush which bears the flowers for the next crop. As the time from flowering to harvest is 14—20 weeks, depending on the cultivar, a crop cycle takes 7—9 months. The other husbandry techniques, such as fertilizing, etc. are timed in a way corresponding to the subtropics where there is naturally a single crop over a one-year cycle. In Thailand, irrigation during the dry season and frequent light pruning to promote the emergence of flowering shoots are employed for continuity of production throughout the year. Where the crop is cycled most fertilizer is applied as a basal dressing at the end of the harvest, if necessary supplemented by a top dressing. If the trees are cropped continuously, fertilizers are applied in several small doses. Minimal foliar nutrient levels are approximately: N 1.65%, P 0.26%, K 1.4%, Ca 1.25% and Mg 0.3%.

In young vigorously growing trees the leading branches can be bent down and tipped to promote sprouting of laterals. At the start of subsequent cycles some of the vigorous branches are cut out to maintain an open tree structure. If the trees bear well the wood ages quickly, so that in mature trees the emphasis is on replacement pruning: cutting back sagging branches to a young twig. In this way tree height and spread are restricted, so that trees can be spaced closely and no ladders are needed (Thailand).

Thinning is necessary for fresh market fruit. Lateral shoots usually bear 2—6 flowers of which only 1 or 2 fruits should remain. In Thailand the fruit is bagged after thinning. This enhances fruit quality and protects against fruit flies. However, since polythene bags are used in which the water vapour condenses, the fruit has to be harvested green to prevent rot. In the Philippines paper bags are used.

Diseases and Pests

Trees may wilt following infection by various soil fungi and in Thailand root rot caused by Phytophthora spp. is also thought to kill trees. The leaves are little affected by diseases, but anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) which is more serious on the fruit, also affects the leaves. Blossom-end rot can become a serious disease in the rainy season; there may be physiological as well as pathological causes. Mucor rot, caused by the fungus Mucor hiemalis, spoils fruit punctured by insects. One often sees young fruit blackened and mummified by Glomerella cingulata or Diplodia natalensis. Fruit canker, circular raised corky spots infected by Pestalotia psidii, is also common. Orchard sanitation in the form of early removal of infected plant parts, helps to reduce infections. Chemical control may be needed in the rainy season; dithane is recommended against blossom-end rot and fruit canker, with additional control of anthracnose.

Fruit flies are the most important pest; guava is a major host to species of Anastrepha, Ceratitis, Dacus and Argyresthia. Bagging the fruit is the main control method in continuously cropped orchards; if the crop is cycled, spraying with fenthion or use of bait sprays provide additional means of control. Sucking insects such as scales, mealy bugs and thrips can largely be checked by predators and control of ants. Leaf-eating caterpillars and beetles may severely damage young trees; early detection greatly facilitates control by spot treatment.

Fruit flies are the most important pest; guava is a major host to species of Anastrepha, Ceratitis, Dacus and Argyresthia. Bagging the fruit is the main control method in continuously cropped orchards; if the crop is cycled, spraying with fenthion or use of bait sprays provide additional means of control. Sucking insects such as scales, mealy bugs and thrips can largely be checked by predators and control of ants. Leaf-eating caterpillars and beetles may severely damage young trees; early detection greatly facilitates control by spot treatment.

Harvesting

Immature fruit do not ripen off the tree. They may soften but do not develop full flavour or colour. Thus the fruit is picked selectively by hand. It is not easy to determine the best time to harvest individual fruit; it has been recommended to pick as the colour changes to pale green with first sign of yellowing, but experience is the best guide. If the harvesting interval exceeds 4 days in warm weather, losses of overripe fruit become a problem. Mechanical harvesting has been used experimentally for processing fruit in Hawaii and Puerto Rico.

Yield

The guava is a fruitful tree and orchards should produce 25—40 t/ha per year. In the tropics prolonged quiescence of large portions of the tree is the main reason for lower yields. The emergence of flowering shoots should be stimulated to realize potential yield. In experiments with crop cycling in Hawaii, yields of about 100 t/ha per year were obtained.

Handling After Harvest

The fruit is delicate and should be handled with great care. To avoid damage, it should be graded and transported in small boxes rather than in large crates immediately after harvest, when it is still firm; it should reach the consumer before it softens. For larger markets storage at 5°C extends post-harvest life by 2 weeks in comparison with storage at 20°C.

Genetic Resources

In leading guava-producing countries more or less extensive cultivar collections from all over the world are maintained, e.g. in the Tropical Fruit Research Station, Alstonville, Australia. Within South-East Asia the collections are still very limited and exchange and testing of promising cultivars is given little attention. There is not much evidence of activity in collecting germplasm within the region of origin.

Breeding

Systematic breeding work was first undertaken in Hawaii to obtain better processing cultivars. Current standards for selection of processing cultivars in Hawaii include: fruit diameter at least 7.5 cm, diameter of cavity no more than 3.75 cm, fruit weight 200—300 g, seed content only 1—2%, dark pink colour, soluble solids 9—12%, vitamin C 300 mg per 100 g, flesh with few stone cells and with characteristic guava flavour. Important criteria for breeding programmes in the major fresh fruit producing countries are yield potential, seedlessness and firm fruit which ripens slowly. In Thailand a hybrid — 'Bangkok Golden Apple' — has been released, a cross between the leading Thai cultivar and an Indonesian seedless type.

Prospects

The guava is an ideal home garden fruit because of its hardiness, high yield, long supply season and high nutritive value. The potential for a larger role of guava in the fresh fruit market appears to be mainly limited by its short shelf life and its susceptibility to fruit flies which make it difficult to fully exploit the high quality of the ripe fruit. On the other hand, the prospects for expanding the market for processed products — mainly paste and juice — are bright within South-East Asia as well as elsewhere.

Literature

Amin, M.N. & Jaiswal, V.S., 1988. Micropropagation as an aid to rapid cloning of a guava cultivar. Scientia Horticulturae 36: 89—95.

Menzel, C.M., 1985. Guava: an exotic fruit with potential in Queensland. Queensland Agricultural Journal 111(2): 93—98.

Nakasone, H.Y., 1983. Past, present and future research in guavas in Hawaii. Paper International Workshop for promoting research on Tropical Fruits. Jakarta, May—June 1983. 17 pp.

Nanthanchai, P., 1983. Research on and production of guava in Thailand. Paper International Workshop for promoting research on Tropical Fruits. Jakarta, May—June 1983. 6 pp.

Singh, A., 1980. Fruit physiology and production. Kalyani Publications, New Delhi, Ludhiana. pp. 323—326.

Menzel, C.M., 1985. Guava: an exotic fruit with potential in Queensland. Queensland Agricultural Journal 111(2): 93—98.

Nakasone, H.Y., 1983. Past, present and future research in guavas in Hawaii. Paper International Workshop for promoting research on Tropical Fruits. Jakarta, May—June 1983. 17 pp.

Nanthanchai, P., 1983. Research on and production of guava in Thailand. Paper International Workshop for promoting research on Tropical Fruits. Jakarta, May—June 1983. 6 pp.

Singh, A., 1980. Fruit physiology and production. Kalyani Publications, New Delhi, Ludhiana. pp. 323—326.

Author(s)

Lita Soetopo

Correct Citation of this Article

Soetopo, L., 1991. Psidium guajava L.. In: Verheij, E.W.M. and Coronel, R.E. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2: Edible fruits and nuts. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.