Record Number

1550

PROSEA Handbook Number

2: Edible fruits and nuts

Taxon

Tamarindus indica L.

Protologue

Sp. Pl.: 34 (1753).

Family

LEGUMINOSAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 24

Synonyms

Tamarindus occidentalis Gaertn. (1791), Tamarindus officinalis Hook. (1851).

Vernacular Names

Tamarind, Indian tamarind (En). Tamarinier (Fr). Indonesia: asam, asam jawa, tambaring. Malaysia: asam jawa. Philippines: sampalok (Tagalog), kalamagi (Bisaya), salomagi (Ilokano). Burma: magyee, majee-pen. Cambodia: 'âm'pül, ampil, khoua me. Laos: khaam, mak kham. Thailand: makham (general), bakham (northern), somkham (peninsular). Vietnam: me, trai me.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

The origin of tamarind is unknown. It is generally believed that it is indigenous to the drier savannas of tropical Africa, but it certainly naturalized long ago in tropical Asia. Tamarind is now cultivated in all tropical countries, even on a plantation scale in India, and it is economically important all over South-East Asia.

Uses

The green fruits and flowers may be used for souring soupy dishes of fish and meat. The ripe fruit of the sweet type is usually eaten fresh, whereas the fruits of sour types are made into juice, jam, syrup and candy. Tamarind seeds are also edible after soaking in water and boiling to remove the seed-coat. Flour from the seed may be made into cake and bread. Roasted seeds are claimed to be superior to groundnuts in flavour. The seed oil — which resembles linseed oil — is suitable for making paint and varnish.

The bark is astringent and tonic and its ash may be given internally as a digestive. Incorporated into lotions or poultices, the bark may be used to relieve sores, ulcers, boils and rashes. It may also be administered as a decoction against asthma and amenorrhea and as a febrifuge. Young leaves may be used in fomentation for rheumatism, applied to sores and wounds, or administered as a poultice for inflammation of joints to reduce swelling and relieve pain. A sweetened decoction of leaves is good against cough and fever. Filtered hot juice of young leaves and a poultice of the flowers are used for conjunctivitis. The pulp may be used as an acid refrigerant, a mild laxative and also to treat scurvy. Powdered seeds may be given to cure dysentery and diarrhoea.

The bark is astringent and tonic and its ash may be given internally as a digestive. Incorporated into lotions or poultices, the bark may be used to relieve sores, ulcers, boils and rashes. It may also be administered as a decoction against asthma and amenorrhea and as a febrifuge. Young leaves may be used in fomentation for rheumatism, applied to sores and wounds, or administered as a poultice for inflammation of joints to reduce swelling and relieve pain. A sweetened decoction of leaves is good against cough and fever. Filtered hot juice of young leaves and a poultice of the flowers are used for conjunctivitis. The pulp may be used as an acid refrigerant, a mild laxative and also to treat scurvy. Powdered seeds may be given to cure dysentery and diarrhoea.

Production and International Trade

Although production should be substantial, statistical records do not usually specify tamarind. The crop in India — the largest producer — was 250 000 t in 1964 and India also exports several thousand tonnes per year, mainly of seed and seed powder, but also some pulp. Export statistics in Thailand for the early 1980s range from 11 000 to 21 000 t of dried pods. In India, Thailand, Central America (Mexico: 4400 ha) and Brazil the crop is to some extent grown in orchards; elsewhere production comes only from trees along roads, in field borders and in home gardens.

Properties

Ripe fruits have 40—50% edible pulp which contains per 100 g: water 17.8—35.8 g, protein 2—3 g, fat 0.6 g, carbohydrates 41.1—61.4 g, fibre 2.9 g, ash 2.6—3.9 g, calcium 34—94 mg, phosphorus 34—78 mg, iron 0.2—0.9 mg, thiamine 0.33 mg, riboflavin 0.1 mg, niacin 1.0 mg and vitamin C 44 mg. Fresh seeds contain 13% water, 20% protein, 5.5% fat, 59% carbohydrates and 2.4% ash. The acidity is caused by tartaric acid, which on ripening does not disappear but is matched more or less by increasing sugar levels. Hence tamarind is said to be simultaneously the most acid and the most sweet fruit.

Description

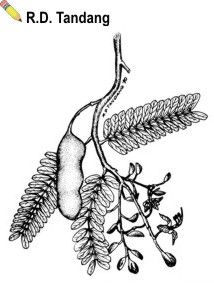

A large evergreen tree, up to 30 m tall, bole usually 1—2 m long, up to 2 m diameter, crown densely foliaged, widely spreading, rounded; bark rough, fissured, greyish-brown. Leaves alternate, stipulate, petiolate, paripinnately compound; petiole up to 1.5 cm long, leaving a prominent scar after falling; blade suboblong in outline, up to 13 cm x 5 cm, with 8—16 pairs of leaflets; leaflets narrowly oblong, 1—3.5 cm x 0.5—1 cm, entire, oblique and rounded at base, rounded to slightly emarginate at apex. Inflorescences lax lateral and terminal racemes, up to 13 cm long; flowers ca. 3 cm long, fragrant; sepals 4, unequal, up to 1.5 cm long; petals 5, the posterior and lateral ones large and showy, cream coloured with brown-red veins, the 2 anterior ones much reduced, linear, white; stamens 3; pistil 1, up to 18-ovuled. Fruit a subcylindrical, straight or curved, indehiscent pod with rounded ends, up to 14 cm x 4 cm, up to 10-seeded, often irregularly constricted between the seeds; exocarp crustaceous, greyish or more usually scurfy brown, with some strong fibrous threads inside; mesocarp thick-syrupy, blackish-brown; endocarp thin, leathery. Seeds irregularly shaped, flattened rhomboid, up to 18 mm long, very hard, brown.

Image

| Tamarindus indica L. - flowering and fruiting branch |

Growth and Development

The seeds remain viable for many months and germinate within 2 weeks after sowing. Growth is generally slow, seedling height increasing by about 60 cm annually. The juvenile phase lasts 4—5 years or longer. At higher latitudes shoots grow mainly in spring, flower throughout the summer and pods ripen in the spring, the period from flowering to harvest being quite long (about 8 months until full maturity). Very little is known about the growth rhythm in the tropics. In the monsoon climate of East Java the tree changes its leaves towards the end of the dry season (some trees in September, others in October—November). Some trees may be nearly leafless for a while, but normally they remain foliated. More or less incidental shoot growth continues through the rainy season (November—April) into the dry season, but in July—August the trees are virtually quiescent. Flowers emerge on the new shoots that mark the leaf change, but some trees flower later, even as late as February when the shoots have long matured. The fruit ripens mainly in June—September.

In Thailand the fruiting season is December—February, in the Philippines from May to December with a peak in August—October. The flowers produce nectar and are probably pollinated by insects; self-pollination results in seeded pods.

In Thailand the fruiting season is December—February, in the Philippines from May to December with a peak in August—October. The flowers produce nectar and are probably pollinated by insects; self-pollination results in seeded pods.

Other Botanical Information

Tamarindus L. is a monospecific genus. In the past a distinction was made between tamarinds from the West and the East Indies:

— West Indies: Tamarindus occidentalis: pod up to 3 times longer than wide, containing 1—4 seeds;

— East Indies: Tamarindus indica: pod up to 6 times or more longer than wide, containing 6—12 seeds.

There are several tamarind cultivars, differing mainly in colour and sweetness of the flesh. In Thailand named cultivars of the sweet type (makahm wahn) are grown in orchards, e.g. 'Muen Chong', 'Nazi Zad', 'Si Chompoo'. 'Manila Sweet' is a cultivar of the Philippines.

— West Indies: Tamarindus occidentalis: pod up to 3 times longer than wide, containing 1—4 seeds;

— East Indies: Tamarindus indica: pod up to 6 times or more longer than wide, containing 6—12 seeds.

There are several tamarind cultivars, differing mainly in colour and sweetness of the flesh. In Thailand named cultivars of the sweet type (makahm wahn) are grown in orchards, e.g. 'Muen Chong', 'Nazi Zad', 'Si Chompoo'. 'Manila Sweet' is a cultivar of the Philippines.

Ecology

Tamarind grows well over a wide range of soil and climatic conditions. It is found in places with sandy to clay soils, at low to medium altitudes (up to 1000 m, sometimes to 1500 m), where rainfall is evenly distributed or where the dry season is long and very pronounced. Its extensive root system contributes to its resistance to drought and strong winds. In the wet tropics (rainfall > 4000 mm) the tree does not flower, and wet conditions during the final stages of fruit development are detrimental. Young trees are killed by the slightest frost, but older trees seem more cold-resistant than mango, avocado and lime trees.

Propagation and planting

Tamarind may be propagated by seeds and by marcotting, grafting and budding. Seedlings are big enough to be planted out in the field in a year or less, but they do not come true to type. Outstanding mother trees are propagated asexually. Shield and patch budding and cleft grafting are fast and reliable methods and at present used in large-scale propagation in the Philippines, the best time being the cool and dry months of November to January. Budded or grafted trees are planted in the field at the onset of the rainy season (May to June in the Philippines) at a spacing of 8—10 m.

Husbandry

Trees generally receive minimal care, but in orchards in Thailand's central delta intensive cropping is practised. This is possible because grafted trees come into bearing within 3—4 years. Sweet cultivars are planted and good early crops limit extension growth; presumably the high water table which prevents deep rooting also helps to dwarf the trees. Size-control measures include close spacing (about 500 trees per ha) and pruning to rejuvenate the fruiting wood. The trees are treated in a similar manner as other fruit crops in the area with respect to irrigation, manuring and crop protection.

Diseases and Pests

The trees are hosts to such pests as shothole borers, toy beetles, leaf-feeding caterpillars, bagworms, mealy bugs and scale insects. In some seasons, fruit borers may inflict serious damage to maturing fruits causing a great reduction in marketable yield. Diseases which have been reported from India include several tree rots and a bacterial leaf-spot.

Harvesting

In the Philippines, the fruits of sour types are harvested at 2 stages: green for flavouring and ripe for processing. Fruits of sweet cultivars are also harvested at 2 stages: half ripe or 'malasebo' stage and ripe stage. At the half-ripe stage the skin is easily peeled off; the pulp is yellowish-green and has the consistency of an apple. At the ripe stage, the pulp shrinks because of loss of moisture, and changes to reddish-brown and becomes sticky. If the whole pod is to be marketed, the fruit should be harvested by clipping to avoid damaging the pods. Eventually the pods abscise naturally.

Yield

Yield records are scarce. Up to 170 kg/year of prepared pulp per (large) tree has been reported from India and Sri Lanka; 80—90 kg is said to be an average yield. At 100 trees per ha this would mean 8—9 t of prepared pulp per ha per year. In the Philippines 200—300 kg pods per tree is considered a good yield. The lack of information on biennial bearing suggests that bearing is fairly regular.

Handling After Harvest

Green fruits for cooking, and half-ripe and ripe fruits for fresh consumption are sold by weight in the markets. Ripe fruits for processing are peeled, fibre strands are removed, and then they are sold by weight in plastic containers. The fruit of sweet cultivars commands a much higher price than the sour fruit.

Genetic Resources

The greatest diversity of tamarind types is found in the African savannas. Selected material exhibits tolerance to drought, wind, poor soils, waterlogging, high pH, low pH and grazing. The Institute of Plant Breeding in Los Baños, the Philippines, contains a germplasm collection (46 accessions).

Prospects

The much-appreciated qualities of the tamarind and its adaptability to different soils and climates enabled it to conquer the tropics in the remote past; the tree and its fruit are still highly prized today. It is, therefore, all the more surprising that so little is known about tree phenology, floral biology, husbandry, yield and genetic diversity. The contribution of science to the knowledge which farming communities have accumulated is minimal; until this situation changes it is difficult to assess the prospects for the tamarind.

Literature

Carangal, A.R., Gonzalez, L.G. & Daguman, I.L., 1961. The acid constituents of some Philippine fruits. The Philippine Agriculturists 44: 514—519.

Coster, C., 1923. Lauberneuerung und andere periodische Lebensprozesse in dem trockenen Monsun-Gebiet Ost-Javas. [Leaf change and other periodical life processes in the dry monsoon area of East Java]. Annales Jardin Botanique, Buitenzorg 33: 117—189.

Duke, J.A., 1981. Handbook of legumes of world economic importance. Plenum Press, New York. pp. 228—230. Jansen, P.C.M., 1981. Spices, condiments and medicinal plants in Ethiopia, their taxonomy and agricultural significance. PUDOC, Wageningen. pp. 244—256.

Pratt, D.S. & del Rosario, J.I., 1913. Philippine fruits: their composition and characteristics. Philippine Journal of Science A8: 59—80.

Soetisna, U. & Hidajat, E., 1977. Pohon asam (Tamarindus indica L.) [Tamarind tree (Tamarindus indica L.)]. Buletin Kebun Raya 3(2): 63—65.

Coster, C., 1923. Lauberneuerung und andere periodische Lebensprozesse in dem trockenen Monsun-Gebiet Ost-Javas. [Leaf change and other periodical life processes in the dry monsoon area of East Java]. Annales Jardin Botanique, Buitenzorg 33: 117—189.

Duke, J.A., 1981. Handbook of legumes of world economic importance. Plenum Press, New York. pp. 228—230. Jansen, P.C.M., 1981. Spices, condiments and medicinal plants in Ethiopia, their taxonomy and agricultural significance. PUDOC, Wageningen. pp. 244—256.

Pratt, D.S. & del Rosario, J.I., 1913. Philippine fruits: their composition and characteristics. Philippine Journal of Science A8: 59—80.

Soetisna, U. & Hidajat, E., 1977. Pohon asam (Tamarindus indica L.) [Tamarind tree (Tamarindus indica L.)]. Buletin Kebun Raya 3(2): 63—65.

Author(s)

R.E. Coronel

Correct Citation of this Article

Coronel, R.E., 1991. Tamarindus indica L.. In: Verheij, E.W.M. and Coronel, R.E. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2: Edible fruits and nuts. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.