Record Number

2173

PROSEA Handbook Number

8: Vegetables

Taxon

Hibiscus sabdariffa L.

Protologue

Sp. pl.: 695 (1753).

Family

MALVACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 4x = 72

Synonyms

Hibiscus digitatus Cav. (1787).

Vernacular Names

Roselle, red sorrel, Indian sorrel, Jamaican sorrel (En). Oseille de Guinée, roselle (Fr). Indonesia: gamet walanda (Sunda), kasturi roriha (Ternate). Malaysia: asam susur. Philippines: roselle (Tagalog), kubab (Ifugao), talingisag (Subanon). Cambodia: slök chuu. Laos: sômz ph'oox dii. Thailand: krachiap-daeng (central), krachiap-prieo (central), phakkengkheng (northern). Vietnam: b[uj]p gi[aas]m.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Although not known with certainty, Hibiscus sabdariffa is most probably of African origin, where it seems to have been domesticated originally for its seeds. The use of the leaves and the fleshy calyx developed much later and these vegetable types were introduced into America and India in the 17th Century. It was in Asia that types suitable for the production of fibres were selected. Roselle now has pantropical distribution, usually in cultivation, sometimes as an escape.

Uses

Young shoots and leaves are used raw or cooked as vegetable. They have a sour taste and are slightly mucilaginous. The fleshy calyces are widely used in making beverages (roselle syrup, roselle wine), jams and jellies. The calyces can also be dried and stored for later use. In Egypt they are used to prepare the very popular acid roselle tea. In some parts of Africa the seeds are eaten roasted in the same way as sesame, and can be used as a source of edible oil. The bast fibre is a good substitute for jute; it is used for making cordage, rope and sacks, and also in the paper industry. Roselle also has medicinal applications. The calyces are diuretic and are believed to decrease blood cholesterol. The seeds are mildly laxative and diuretic.

Production and International Trade

Roselle is grown in many tropical countries primarily for its leaves and edible calyces. It is among the most important leafy vegetables in the drier parts of West Africa. In South-East Asia it is a typical home garden plant. As a fibre crop it is mainly important in South Asian countries (India, Bangladesh) and in China, and to a lesser extent in South-East Asia (Thailand, Indonesia). Roselle accounts for about 20% (700 000 t annually) of jute-like fibres.

Properties

Per 100 g edible portion, the leaves contain: water 85 g, protein 3.3 g, fat 0.3 g, carbohydrates 9 g, fibre 1.6 g, Ca 213 mg, P 93 mg, Fe 4.8 mg, ß-carotene 4.1 mg, vitamin B1 0.17 mg, vitamin B2 0.45 mg, niacin 1.2 mg, vitamin C 54 mg. The energy value is 180 kJ/100 g. The calyces are considerably lower in protein and vitamin contents; they contain about 4% citric acid. The seeds contain 17—20% of an edible oil, which is similar in properties to cotton-seed oil. Roselle fibre is coarser and stiffer than jute fibre, but equal in strength. It is much stronger than kenaf fibre (Hibiscus cannabinus L.). The 1000-seed weight is 15—25 g.

Description

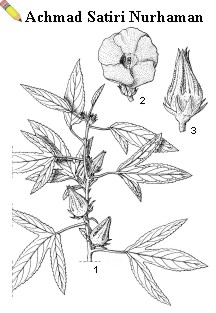

Robust annual, erect, herb, up to 4 m tall, often with much anthocyanin in the green parts. Stem often woody at the base. Leaves simple, alternate, polymorphic, 8—15 cm x 6—14 cm, with a nectary on the midrib beneath; the lower leaves often undivided, ovate; the upper leaves palmately 3—5-parted with lanceolate segments; petiole 4—12 cm long. Flowers solitary, axillary and showy, yellow or pink with a dark purple basal spot; epicalyx segments 7—10, without an appendage, reddish, linear and usually fleshy; calyx 5-lobed, 1—2 cm long, with a nectary on the costae outside, usually becoming large and fleshy after anthesis, accrescent to 5 cm and closely enveloping the capsule, dark purple or red; corolla with 5 petals, not widely opened, pale yellow or pale pink with dark purple basal spot; staminal column erect, 1.5—2 cm long, bearing anthers almost from the base; style arms 5, short, each ending in a discoid stigma. Fruit an ovoid capsule, 2—2.5 cm x 1.5—2.5 cm, obtuse, pilose, many-seeded, dehiscent by 5 valves. Seed reniform, 4—7 mm long, blackish brown, pilose.

Image

| Hibiscus sabdariffa L. - 1, flowering shoot; 2, flower; 3, capsule surrounded by fleshy calyx |

Growth and Development

The vegetative growth phase normally lasts 4—5 months, but flowering may start as early as 2? months or as late as 7—8 months after sowing. Roselle is a self-pollinated crop, but some cross-pollination by insects may occur. Fruit ripening takes 2—3 months from pollination.

Other Botanical Information

The distinction between vegetable and fibre types is best expressed in a cultivar group classification:

— cv. group Sabdariffa (synonym: var. sabdariffa) consists of bushy, much-branched forms, up to 2 m tall, with a very fleshy calyx, lacking hairs and prickles, normally cultivated as a leafy vegetable or for the edible calyx;

— cv. group Altissima (synonym: var. altissima Wester) consists of tall, unbranched forms, up to 4 m tall, usually with inedible calyces, frequently beset with hairs and prickles, grown for their bast fibres.

Hibiscus sabdariffa (2n = 72) is most probably an allotetraploid derived from Hibiscus asper Hook.f. (2n = 36) and a second still unknown species with 2n = 36.

— cv. group Sabdariffa (synonym: var. sabdariffa) consists of bushy, much-branched forms, up to 2 m tall, with a very fleshy calyx, lacking hairs and prickles, normally cultivated as a leafy vegetable or for the edible calyx;

— cv. group Altissima (synonym: var. altissima Wester) consists of tall, unbranched forms, up to 4 m tall, usually with inedible calyces, frequently beset with hairs and prickles, grown for their bast fibres.

Hibiscus sabdariffa (2n = 72) is most probably an allotetraploid derived from Hibiscus asper Hook.f. (2n = 36) and a second still unknown species with 2n = 36.

Ecology

Hibiscus sabdariffa is a short-day plant and is often used as a laboratory plant in the study of photoperiod sensitivity. It requires 12—12? hours daylength for flowering and fruiting; in Java (6—8°S) usually no flowering is observed during the period December—March. The length of the vegetative period can thus be manipulated through the sowing date. Roselle tolerates a wide range of soil conditions, but for economic yields, soils should be well-supplied with organic material and essential nutrients. It is reasonably drought resistant.

Agronomy

Roselle is usually grown from seed, but can also be propagated by stem cuttings. For commercial plantings seeds are sown in a nursery and transplanted when they are 4 weeks old and 10—12 cm high. In West Africa, roselle or 'dah' is usually broadcast at low densities in fields of the main food crops.

For calyx production, plants are relatively widely spaced (120 cm x 90 cm, or 10 000 plants/ha). The calyces must be picked about 15—20 days after flowering. Well-developed plants may yield up to 250 calyces, corresponding to 1—1.5 kg per plant. Crop yields vary from 5—15 t/ha. For leaf production, plants can be spaced closer, e.g. 60 cm x 100 cm. Leaves or young shoots can be harvested from the third month onwards. Yields up to 10 t/ha have been reported. When flowering interferes too much with vegetative development, harvesting of leafy shoots can be stopped in favour of a subsequent crop of calyces to be harvested 4—5 months after sowing.

When grown for fibre, roselle is planted at very close spacings of 12—20 cm x 12—20 cm with 1—2 plants per hill. Harvesting is done before the onset of flowering (delayed by long days) 4—5(—8) months after sowing. The harvested stems are retted in water for 5—14 days, then the bark is stripped and gently beaten to separate the fibres which are then washed and dried. Fibre yields are about 1.5—2.5 t/ha. Three quality groups of fibres are distinguished, based on length, colour, purity and stiffness. Seed yields of 200—1500 kg/ha have been reported.

Important diseases are leaf-spot (Cercospora hibisci) and foot rot (Phytophthora parasitica). Roselle has many pests in common with other malvaceous crops like cotton and okra. Common pests are cotton stainer bugs (Dysdercus superstitiosus), bollworms (Earias biplaga, Earias insulana), flea beetles (Podagrica spp.) and nematodes.

For calyx production, plants are relatively widely spaced (120 cm x 90 cm, or 10 000 plants/ha). The calyces must be picked about 15—20 days after flowering. Well-developed plants may yield up to 250 calyces, corresponding to 1—1.5 kg per plant. Crop yields vary from 5—15 t/ha. For leaf production, plants can be spaced closer, e.g. 60 cm x 100 cm. Leaves or young shoots can be harvested from the third month onwards. Yields up to 10 t/ha have been reported. When flowering interferes too much with vegetative development, harvesting of leafy shoots can be stopped in favour of a subsequent crop of calyces to be harvested 4—5 months after sowing.

When grown for fibre, roselle is planted at very close spacings of 12—20 cm x 12—20 cm with 1—2 plants per hill. Harvesting is done before the onset of flowering (delayed by long days) 4—5(—8) months after sowing. The harvested stems are retted in water for 5—14 days, then the bark is stripped and gently beaten to separate the fibres which are then washed and dried. Fibre yields are about 1.5—2.5 t/ha. Three quality groups of fibres are distinguished, based on length, colour, purity and stiffness. Seed yields of 200—1500 kg/ha have been reported.

Important diseases are leaf-spot (Cercospora hibisci) and foot rot (Phytophthora parasitica). Roselle has many pests in common with other malvaceous crops like cotton and okra. Common pests are cotton stainer bugs (Dysdercus superstitiosus), bollworms (Earias biplaga, Earias insulana), flea beetles (Podagrica spp.) and nematodes.

Genetic Resources and Breeding

Germplasm is maintained by the Australian Tropical Forages Genetic Resources Centre, CSIRO, Queensland, Australia, by the Jute Agricultural Research Institute, Barrackpore, West Bengal, India, and by the International Jute Organization (IJO), Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Selection and breeding work has been limited to types grown for fibre, and a few improved cultivars have been released. There seems to be some risk of genetic erosion in India and Bangladesh, but not in other parts of the world where the vegetable types predominate.

Selection and breeding work has been limited to types grown for fibre, and a few improved cultivars have been released. There seems to be some risk of genetic erosion in India and Bangladesh, but not in other parts of the world where the vegetable types predominate.

Prospects

Roselle is an interesting green because of its good drought resistance. It offers a useful combination of edible vegetative and generative parts. The production of fibre will remain important, but high labour costs and competition from chemically fabricated substitutes may cause a shift towards its use in paper pulp production.

Literature

Boulanger, J., 1989. Kenaf und Roselle [Kenaf and roselle]. In: Rehm, S. (Editor): Handbuch der Landwirtschaft und Ernährung in den Entwicklungsländern. Bd. 4. Spezieller Pflanzenbau in den Tropen und Subtropen [Handbook of agriculture and nutrition in underdeveloped countries. Vol. 4. Special plant cultivation in the tropics and subtropics]. 2nd edition. Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart, Germany. pp. 568-573.

Stevels, J.M.C., 1990. Légumes traditionnels du Cameroun, une étude agro-botanique [Traditional vegetables of Cameroun, an agro-botanic study]. Thesis. Wageningen Agricultural University Papers 90-1, Wageningen, the Netherlands. pp. 177-188.

Tindall, H.D., 1983. Vegetables in the tropics. MacMillan, London, United Kingdom. pp. 332-337.

van Borssum Waalkes, J., 1966. Malesian Malvaceae revised. Blumea 14(1): 64-65.

Wilson, F.D. & Menzel, M.Y., 1964. Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus), roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa). Economic Botany 18: 80-91.

Stevels, J.M.C., 1990. Légumes traditionnels du Cameroun, une étude agro-botanique [Traditional vegetables of Cameroun, an agro-botanic study]. Thesis. Wageningen Agricultural University Papers 90-1, Wageningen, the Netherlands. pp. 177-188.

Tindall, H.D., 1983. Vegetables in the tropics. MacMillan, London, United Kingdom. pp. 332-337.

van Borssum Waalkes, J., 1966. Malesian Malvaceae revised. Blumea 14(1): 64-65.

Wilson, F.D. & Menzel, M.Y., 1964. Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus), roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa). Economic Botany 18: 80-91.

Author(s)

T. Boonkerd, B. Na Songkhla & W. Thephuttee

Correct Citation of this Article

Boonkerd, T., Na Songkhla, B. & Thephuttee, W., 1993. Hibiscus sabdariffa L.. In: Siemonsma, J.S and Piluek, K (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 8: Vegetables. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.