Record Number

2989

PROSEA Handbook Number

11: Auxiliary plants

Taxon

Azadirachta indica A.H.L. Juss.

Protologue

Mém. Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat. Paris 19: 221, t.13, fig. 5 (1832).

Family

MELIACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 28, 30

Synonyms

Melia azadirachta L. (1753), Melia indica (A.H.L. Juss.) Brandis (1874), Antelaea azadirachta (L.) Adelb. (1948).

Vernacular Names

Neem, Indian lilac, margosa tree (En). Neem (Am). Azadirac de l'Inde, margosier, margousier (Fr). Indonesia: mimba (Java), membha (Madura), intaran (Bali). Malaysia: baypay, mambu, veppam (Peninsular). Papua New Guinea: neem. Philippines: neem. Singapore: kohomba, nimba, veppam. Burma (Myanmar): tamarkha, thinboro, tamar. Cambodia: sdau. Laos: kadau. Thailand: khwinin (general), sadao (central), saliam (northern). Vietnam: s[aaf]u d[aa]u.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

The exact origin of neem is unknown. It is thought to have originated in the Assam—Burma (Myanmar) region and to be distributed naturally throughout the Indian subcontinent. It has long been cultivated in Peninsular Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand, where it is completely naturalized and has modified deciduous forests. In the 19th Century South Asian emigrants took it to Fiji, Mauritius and Guyana, and the British to Sudan, Egypt, East Africa, and sub-Sahel West Africa, where it is widely grown and has also naturalized. It has recently been introduced into tropical South and Central America, Florida, Hawaii, Saudi Arabia, the Philippines, and northern Australia. Now it is probably one of the fastest-spreading trees and has become pan-tropical.

Uses

Neem is a multipurpose tree, grown for shade and shelter, for timber and fuel, to control erosion and improve soils, while the oil from the seed is used in soap manufacturing. In the Indian subcontinent it is most famous for its medicinal and insecticidal properties. The large crown of neem makes it an effective shade tree, planted widely as an avenue tree in towns and villages and along roads in many tropical countries. Recently, 50 000 neem trees have been planted in the Arafath plane near Mecca in Saudi Arabia, to provide shade to Muslem pilgrims. Because of its low branching, neem is grown as a wind-break. In South-East Asia it is mainly planted to protect and improve very poor soils. In East Java, neem trees are tapped to extract gum exudates used for making paper glue.

The tree's hard, termite-resistant wood is used in construction, for making carts, agricultural implements and furniture, and is suitable for the manufacture of plywood and blockboard. It makes a good firewood and is extremely important as fuel for example in West Africa. Neem twigs are commonly used to clean teeth, whereas young twigs and young flowers are occasionally consumed as a vegetable. The leaves, though very bitter, are used as a dry season fodder.

Neem seed oil is used in South Asia for soap making. The residue after oil extraction or 'neem cake' serves as livestock feed and fertilizer. Recently, it has been used as an admixture or coating of urea fertilizer to reduce losses of N from urea through denitrification.

Neem is best known for its medicinal uses, described early on in classical Hindu texts, and detailed in the Ayurvedic and Unani schools of medicine. People bathe in water with neem extracts to treat health problems. Various parts have anthelmintic, antiperiodic, antiseptic, diuretic, and purgative actions, and are also used to treat boils, pimples, eye diseases, hepatitis, leprosy, rheumatism, scrofula, ringworm and ulcers. In Africa neem leaves are chewed and an infusion from the leaves is taken to prevent conception and induce abortion. In modern medicine, antibacterial, antifungal and anti-inflammatory effects have been demonstrated, but are still in the early stages of testing. Small but significant effects against malaria parasites have been found and the active chemicals have been isolated. Preliminary experiments indicate that neem-seed extracts may contribute to the control of Chaga's disease, a nerve disease affecting about 20 million people in Latin America caused by Tripanosoma cruzi, a parasite related to the cause of the African sleeping sickness, and transferred by kissing bugs (Rhodnius spp.). The extracts mainly act by repelling the vector, but also by interfering with its moulting and by killing the parasites in the vector. Neem oil has a strong spermicidal action and possibly prevents the implantation of the ovule. A neem oil-based product 'Sensal' is being marketed in India as an intravaginal contraceptive.

The tree's upcoming promise builds upon its traditional use for pest control, especially of storage insects. In northern India neem leaves are mixed with legume or cereal grain to prevent insect damage. More than 200 species of insects, mites, and nematodes, including destructive crop pests are controlled by extracts from leaves, seed, bark, or flowers. Over 30 pesticides based on azadirachtin, one of neem's many biologically active components, are being marketed and several have been registered by the Environmental Protection Agency of the United States. Commercial products are also available against lice and fleas of animals. Mosquito-repellent coils are among neem's other emerging uses.

The tree's hard, termite-resistant wood is used in construction, for making carts, agricultural implements and furniture, and is suitable for the manufacture of plywood and blockboard. It makes a good firewood and is extremely important as fuel for example in West Africa. Neem twigs are commonly used to clean teeth, whereas young twigs and young flowers are occasionally consumed as a vegetable. The leaves, though very bitter, are used as a dry season fodder.

Neem seed oil is used in South Asia for soap making. The residue after oil extraction or 'neem cake' serves as livestock feed and fertilizer. Recently, it has been used as an admixture or coating of urea fertilizer to reduce losses of N from urea through denitrification.

Neem is best known for its medicinal uses, described early on in classical Hindu texts, and detailed in the Ayurvedic and Unani schools of medicine. People bathe in water with neem extracts to treat health problems. Various parts have anthelmintic, antiperiodic, antiseptic, diuretic, and purgative actions, and are also used to treat boils, pimples, eye diseases, hepatitis, leprosy, rheumatism, scrofula, ringworm and ulcers. In Africa neem leaves are chewed and an infusion from the leaves is taken to prevent conception and induce abortion. In modern medicine, antibacterial, antifungal and anti-inflammatory effects have been demonstrated, but are still in the early stages of testing. Small but significant effects against malaria parasites have been found and the active chemicals have been isolated. Preliminary experiments indicate that neem-seed extracts may contribute to the control of Chaga's disease, a nerve disease affecting about 20 million people in Latin America caused by Tripanosoma cruzi, a parasite related to the cause of the African sleeping sickness, and transferred by kissing bugs (Rhodnius spp.). The extracts mainly act by repelling the vector, but also by interfering with its moulting and by killing the parasites in the vector. Neem oil has a strong spermicidal action and possibly prevents the implantation of the ovule. A neem oil-based product 'Sensal' is being marketed in India as an intravaginal contraceptive.

The tree's upcoming promise builds upon its traditional use for pest control, especially of storage insects. In northern India neem leaves are mixed with legume or cereal grain to prevent insect damage. More than 200 species of insects, mites, and nematodes, including destructive crop pests are controlled by extracts from leaves, seed, bark, or flowers. Over 30 pesticides based on azadirachtin, one of neem's many biologically active components, are being marketed and several have been registered by the Environmental Protection Agency of the United States. Commercial products are also available against lice and fleas of animals. Mosquito-repellent coils are among neem's other emerging uses.

Production and International Trade

In India more than 18 000 t of neem-seed oil is used for soap making. Assuming a fruit yield of 25 kg per tree and an oil content of 10%, this oil must come from about 7.2 million trees. Less than 25% of India's neem trees (in 1975: 25 million) are currently exploited. International trade seems limited to small quantities of leaves imported by two American companies manufacturing neem-based pesticides. Neem oil is valued at about US$ 700/t (1990).

Properties

Neem seed contains 20(—50)% oil. The oil (and to a lesser extent the leaves) contain many biologically active tetranortriterpenoid compounds, especially limonoids. The following groups of limonoids are the most important: azadirachtin, meliacarpin, nimbin, nimbolinin and salannin. Azadirachtin (C25H44O16), a steroid-like, highly oxidized tetranortriterpenoid, structurally similar to insect hormones (ecdysones), has deterrent, antifeedant, anti-ovipositional, growth-disrupting, fecundity and fitness-disrupting properties in insects and several other groups of animals. By blocking the release of these hormones, azadirachtin appears to disrupt the moulting cycle of the insects. Azadirachtin concentrations in seed range from 2—4 mg/g, a maximum of 9 mg/g is reported from Senegal. Biological activity appears greater in trees from drier areas. In hot climates, the azadirachtin concentration is lower. However, the relative roles of genetic and environmental factors are not yet clear. The other compounds of neem are less well studied. Compounds of the azadirone, gedunnin, meliacarpin, nimbin, salannin and vilasinin groups of tetranortriterpenoids appear to be powerful feeding inhibitors, while the nimbolinins and gedunnins have growth-disrupting properties. Compounds of the nimbin group are also bactericidal and cytotoxic, while nimbin and nimbolinin may have anti-viral properties. Other chemically important compounds found in neem include glycerides, polysaccharides, sulphurous compounds, flavonoids and their glycerides, amino acids, and aliphatic compounds.

The wood of neem is hard and resembles mahogany. The density of the wood is 720—930 kg/m3 at 12% moisture content. The heartwood is reddish when freshly exposed, but fades in sunlight to reddish-brown, clearly demarcated from the greyish-white sapwood. The wood is aromatic when fresh and beautifully mottled. The grain is narrowly interlocked, medium to coarse in texture and often uneven. The timber seasons well with little degrade. Pre-boring is necessary when nailed. The wood is durable even in exposed situations, and not attacked by termites or woodworm. It is easy to work by hand or machine, but does not polish well. The energy value of the wood is 20 830 kJ/kg. The energy value of neem seed oil is 45 300 kJ/kg. Neem charcoal is of good quality with an energy value only slightly below that of coal.

Neem leaves contain per 100 g dry matter: crude protein 12—18 g, crude fibre 11—23 g, N-free extract 43—67 g, ash 8—18 g, Ca 1—4 g, P 0.1—0.3 g. The weight of 1000 seeds is (105—)185—270(—350) g.

The wood of neem is hard and resembles mahogany. The density of the wood is 720—930 kg/m3 at 12% moisture content. The heartwood is reddish when freshly exposed, but fades in sunlight to reddish-brown, clearly demarcated from the greyish-white sapwood. The wood is aromatic when fresh and beautifully mottled. The grain is narrowly interlocked, medium to coarse in texture and often uneven. The timber seasons well with little degrade. Pre-boring is necessary when nailed. The wood is durable even in exposed situations, and not attacked by termites or woodworm. It is easy to work by hand or machine, but does not polish well. The energy value of the wood is 20 830 kJ/kg. The energy value of neem seed oil is 45 300 kJ/kg. Neem charcoal is of good quality with an energy value only slightly below that of coal.

Neem leaves contain per 100 g dry matter: crude protein 12—18 g, crude fibre 11—23 g, N-free extract 43—67 g, ash 8—18 g, Ca 1—4 g, P 0.1—0.3 g. The weight of 1000 seeds is (105—)185—270(—350) g.

Description

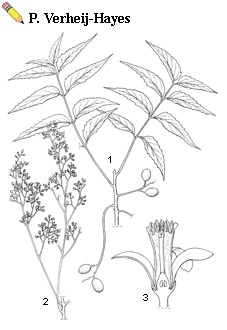

A small to medium-sized, usually evergreen tree, up to 15(—30) m tall with round, large crown up to 10(—20) m in diameter; branches spreading; bole branchless for up to 7.5 m, up to 90 cm in diameter, sometimes fluted at base; bark moderately thick, with small scattered tubercles, deeply fissured and flaking in old trees, dark grey outside and reddish inside, with colourless, sticky foetid sap. Leaves alternate, crowded near the end of branches, simply pinnate, 20—40 cm long, exstipulate, light green, with 2 pairs of glands at the base, otherwise glabrous; petiole 2—7 cm long, subglabrous; rachis channelled above; leaflets 8—19, very short-petioluled, alternate proximally and more or less opposite distally, ovate to lanceolate, sometimes falcate, (2—)3.5—10 cm x 1.2—4.0 cm, glossy, serrate, apex acuminate, base unequal. Inflorescence an axillary, many-flowered thyrse, up to 30 cm long; bracts minute and caducous; flowers bisexual or male on the same tree, actinomorphic, small, 5-merous, white or pale yellow, slightly sweet scented; calyx lobes imbricate, broadly ovate and thin, puberulous inside; petals free, imbricate, spathulate, spreading, ciliolate inside; stamens 10, filaments fused into a 10-lobed staminal tube, glabrous and slightly ribbed outside, anthers sessile, opposite the rounded to laciniate lobes; disk annular, fused to the base of the ovary; ovary superior, style slender, stigma capitate, 3-lobed. Fruit a 1(—2)-seeded drupe, ellipsoidal, 1—2 cm long, greenish, greenish-yellow to yellow or purple when ripe; exocarp thin, mesocarp pulpy, endocarp cartilaginous. Seed ovoid or spherical, apex pointed, testa thin. Seedling with epigeal germination; cotyledons thick, fleshy, elliptical with a rounded apex and sagittate base; first pair of leaves opposite, subsequent pairs either opposite or alternate, first few leaves usually trifoliolate, later 5-foliolate with deeply incised, pinnatifid, or partite leaflets.

Image

| Azadirachta indica A.H.L. Juss. - 1, fruiting branch; 2, part of inflorescence; 3, vertical section through flower |

Growth and Development

At germination the radicle emerges at the end of the seed and the hypocotyl arches, withdrawing the cotyledons from the ground. Growth in the first year is generally slow, 15—25 cm in height, becoming faster when the root system that forms associations with vasicular-arbuscular mycorrhyzal fungi is developed. Trees may reach 4—7 m after 3 years and 5—11 m after 5 years. The annual biomass increment of neem plantations has been reported at 3—10 m3/ha. Under moderately favourable conditions mean annual diameter increment is 0.7—1.0 cm, under optimal conditions 2 cm/year may be reached. In irrigated plantations in India 16-year-old trees reached a diameter of 40 cm. Under cool conditions seedling growth ceases and new shoots appear in spring.

Neem trees may start flowering and fruiting at the age of 4—5 years, but economic quantities of seed are produced after 10—12 years. Pollination is by insects. In India, a bitter-tasting honey is produced. Certain isolated trees do not set fruit, suggesting that self-incompatibility occurs. The flowering and fruiting season largely depends on location and habitat. In Thailand neem trees flower from December to February and fruit in March to May. Fruits ripen in about 12 weeks from anthesis and are eaten by bats and birds which distribute the seed. Neem trees can live for over 200 years. They are normally evergreen, but may shed all or part of their leaves under extremely hot and dry conditions. Timing and duration of leaf shedding, flowering and seed set vary across geographic zones and provenances.

Neem trees may start flowering and fruiting at the age of 4—5 years, but economic quantities of seed are produced after 10—12 years. Pollination is by insects. In India, a bitter-tasting honey is produced. Certain isolated trees do not set fruit, suggesting that self-incompatibility occurs. The flowering and fruiting season largely depends on location and habitat. In Thailand neem trees flower from December to February and fruit in March to May. Fruits ripen in about 12 weeks from anthesis and are eaten by bats and birds which distribute the seed. Neem trees can live for over 200 years. They are normally evergreen, but may shed all or part of their leaves under extremely hot and dry conditions. Timing and duration of leaf shedding, flowering and seed set vary across geographic zones and provenances.

Other Botanical Information

The genus Azadirachta A. Juss. is morphologically and anatomically closely related to Melia L., from which it can be easily distinguished by its simply pinnate leaves (bipinnate in Melia). Azadirachta has 2 species: Azadirachta indica and Azadirachta excelsa (Jack) Jacobs. The latter is a larger tree with larger leaves having 14—23 leaflets with entire margins, occurring naturally in Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia and New Guinea and producing valuable timber.

In Thailand, 2 varieties of the neem tree are sometimes recognized: var. indica, referred to as 'sadao India', and var. siamensis Valeton, called 'sadao Thai'. The latter grows wild and is widely distributed in the country; its branches are directed upright, contrary to the more spreading habit of var. indica. Opinions about their taxonomic status vary. Flora Malesiana reduced them to synonyms of Azadirachta indica, other sources have proposed to raise them to species rank. The two varieties can easily be crossed.

In Thailand, 2 varieties of the neem tree are sometimes recognized: var. indica, referred to as 'sadao India', and var. siamensis Valeton, called 'sadao Thai'. The latter grows wild and is widely distributed in the country; its branches are directed upright, contrary to the more spreading habit of var. indica. Opinions about their taxonomic status vary. Flora Malesiana reduced them to synonyms of Azadirachta indica, other sources have proposed to raise them to species rank. The two varieties can easily be crossed.

Ecology

Neem grows under a wide range of conditions. It is found naturally from 0—700 m altitude, but can grow at elevations up to 1500 m. In the Philippines neem growing is largely restricted to the southern islands, as trees are too severely damaged by typhoons in Luzon. Mean annual minimum temperatures may range from 9.5—24.0°C, mean annual maximum temperatures from 26.3—36.7°C. Adult neem trees tolerate some frost, but seedlings are more sensitive. Optimal growth has been observed in areas with an annual rainfall of about 1000 mm, but rainfall may vary from 400—1400 mm. On well-drained soils, up to 2500 mm rainfall is tolerated, but then fruiting is generally poor. Neem does not tolerate waterlogging. Soil textures suitable for neem may range from pure sand to heavy clay. The soil pH may vary between 3 and 9, but best growth occurs on soils with a pH of 6.2—7.0. Neem prefers medium-textured fertile soils, but still performs better than most other species on shallow, poor soils, or on marginal sloping and stony locations, including crevices in sheer rock. It is occasionally found on moderately saline soils, and has been planted in former sugar-cane plantations abandoned because of increasing soil salinity.

Under natural conditions neem does not grow gregariously. In India, it is present in mixed forest with Acacia spp. and Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. ex DC.; in Indonesia, naturalized in lowland monsoon forest. In Africa it is found in evergreen forest and in dry deciduous forest.

Under natural conditions neem does not grow gregariously. In India, it is present in mixed forest with Acacia spp. and Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. ex DC.; in Indonesia, naturalized in lowland monsoon forest. In Africa it is found in evergreen forest and in dry deciduous forest.

Propagation and planting

Neem is generally propagated by seed, but can also be propagated vegetatively by air layering, root and shoot cuttings, grafting, marcotting and tissue culture. Although it is best to harvest the ripe fruits from the tree, fruit collection within 1—2 days of natural dropping also gives satisfactory results and is more practical. The fruits are soaked in water for 1—2 days, depulped and the seeds are dried under shade, and stored in a cool well-ventilated place in cloth or gunny bags. They should not be stored in airtight containers or plastic bags, but should be sown as soon as possible. Mature seeds germinate readily within a week, with a germination rate of 75—90%. Seed remains viable for 4—8 weeks only, but storage of cleaned and dried seeds at 15°C will prolong this period up to 4 months. Kernels (depulped fruits) stored at —20°C retained their viability for as long as 10 years. Seed is normally sown in the nursery in lines at 15—20 cm x 2.5—5 cm, in a sunny place and covered lightly with soil or mulch. Damage by insects or birds eating the radicles can be prevented by covering with netting or by sowing at a depth of 2.5 cm. Seed beds should be watered sparingly and soil should be kept loose to prevent caking. In frost-prone areas seedlings should be protected by a screen. Seedlings are thinned to 15 cm x 15 cm when 2 months old. When they are 7—10 cm tall, with a taproot of about 15 cm long (about 12 weeks old), they are planted out in the field. Direct sowing in sunken beds, trenches, or on ridges also gives satisfactory results. Intercropping neem with pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum (L.) R. Br.) has given good results in northern India.

Neem propagation by root suckers and stem cuttings can be done using 1000 ppm indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and by air layering using IBA or naphtalene-1-acetic acid (NAA). Tissue culture is being tried; fresh cotyledons have been found to be the best source of material.

Neem propagation by root suckers and stem cuttings can be done using 1000 ppm indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and by air layering using IBA or naphtalene-1-acetic acid (NAA). Tissue culture is being tried; fresh cotyledons have been found to be the best source of material.

Husbandry

Under favourable moisture conditions natural regeneration of neem is usually profuse, as seed is widely distributed by bats and birds. Weeding of neem plantations in dry areas is essential, as it cannot withstand competition, especially from grasses. Neem responds well to organic and chemical fertilizers. In West Africa rotation of neem plantations for firewood is 7—8 years at a final spacing of 5 m x 5 m; on good soils with adequate moisture in Haiti it is planted at 2.5 m x 2.5 m and managed with a rotation of only 4 years. As neem coppices well no replanting is necessary after harvesting. Moreover, coppicing is preferred for firewood production, as it facilitates harvesting and management of the plantation. Neem withstands pollarding well, a valuable asset for the use in wind-breaks, but seed production is adversely affected when trees are lopped for fodder.

Diseases and Pests

There are no records of fungi attacking neem in South-East Asia. In India and elsewhere Pseudocercospora subsessilis is the most common fungus attacking the leaves of neem, causing a shothole effect. In India, the bacterium Pseudomonas azadirachtae may damage leaves and a shoot borer damages shoots. Generally, neem appears not to be affected seriously by pests. In South and South-East Asia minor damage is caused by torticid moths (Adoxophyes spp.). Stored neem kernels have reportedly been damaged by Oryzaephilus larvae in India, and by Carpophilus dinudiathus in Ecuador.

Recently, a serious decline of neem has been observed in West Africa. Older foliage is shed, leaving crowns with an open appearance. Tufts of leaves remain at the branch apices, for which the disorder is now known as 'giraffe neck'. Preliminary observations indicate that the decline is not caused by a biotic agent, but is due to site-related stress (e.g. inadequate soil moisture, soil compaction, competition). In the state of Bornu in Nigeria, 80—95% of the neem trees have been seriously affected.

Recently, a serious decline of neem has been observed in West Africa. Older foliage is shed, leaving crowns with an open appearance. Tufts of leaves remain at the branch apices, for which the disorder is now known as 'giraffe neck'. Preliminary observations indicate that the decline is not caused by a biotic agent, but is due to site-related stress (e.g. inadequate soil moisture, soil compaction, competition). In the state of Bornu in Nigeria, 80—95% of the neem trees have been seriously affected.

Harvesting

The harvesting period of fruits is usually limited to 6—8 weeks after the monsoon rains. Leaves may be collected at any time. Pollarding is usually done on 5—10-year-old trees.

Yield

Fruit yield is 10—30 kg/tree annually. Neem plantations in Thailand with a spacing of 2—4 m x 4 m yielded annually 6—7.5 m3 wood per ha in the first 10 years on poor sites and 33—36 m3/ha on favourable sites.

Handling After Harvest

Fruit collected for the extraction of neem oil is depulped immediately after collection, and the stones are dried in the shade and stored in a cool, dry place to avoid deterioration by oxidation, a reduction of the azadirachtin content and aflatoxin production by fungal growth. Properly dried stones can be stored for 8—12 months before oil extraction.

Genetic Resources

Germplasm collections are made, maintained, evaluated and distributed by Winrock International Institute for Agricultural Research in Thailand (Bangkok). Seeds are available commercially e.g. in India, at a price of US$ 0.50—1.00 per kg, excluding freight and certification, and cuttings cost US$ 50 per 100.

Breeding

Phenotypically superior neem trees have been vegetatively propagated in Australia, India and Thailand. FAO and DANIDA have established provenance trials in Africa, Asia and South America.

Prospects

Neem is an excellent multipurpose tree candidate for reforestation programmes. It is well adapted to depleted soils, is tolerant of repeated coppicing and pruning for firewood and a source of valuable oil. The quest for environmentally safe pesticides is increasing and neem's chemical properties provide an excellent source for further exploration. Ideally, neem pesticides should be based on crude extracts containing many of its compounds, rather than on single, refined and concentrated ingredients.

Literature

Ahmed, S. & Grainge, M., 1986. Potential of the neem tree (Azadirachta indica) for pest control and rural development. Economic Botany 40: 201-209.

Kijkar, S., 1992. Handbook: Planting stock production of Azadirachta spp. at the ASEAN-Canada Forest Tree Seed Centre. ASEAN-Canada Forest Tree Seed Centre Project, Muak-Lek, Saraburi, Thailand. 20 pp.

Mabberley, D.J. & Sing, A.M., 1995. Meliaceae. Azadirachta. In: Kalkman, C. et al. (Editors): Flora Malesiana, Series 1, Vol. 12(1). Foundation Flora Malesiana, Leiden, the Netherlands. pp. 341-343.

Read, M.D. & French, J.H. (Editors), 1993. Genetic improvement of neem: Strategies for the future. Winrock International Institute for Agricultural Research, F/FRED Project, Bangkok, Thailand. 194 pp.

Ruskin, F.R., 1992. Neem. A tree for solving global problems. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., United States. 141 pp.

Schmutterer, H. (Editor), 1995. The neem tree Azadirachta indica A. Juss. and other meliaceous plants: sources of natural products for integrated pest management, medicine and industry and other purposes. VCH, Weinheim, Germany. 696 pp.

Tewari, D.N., 1992. Monograph on neem. R.P. Singh Gahlot for International Book Distributors, Dehra Dun, India. 279 pp.

Tampubolon, A.P. & Alrasyid, H., 1989. The neem tree and its developmental prospects in rainfed zones in Indonesia. Duta Rimba 15(109-110): 9-12.

Kijkar, S., 1992. Handbook: Planting stock production of Azadirachta spp. at the ASEAN-Canada Forest Tree Seed Centre. ASEAN-Canada Forest Tree Seed Centre Project, Muak-Lek, Saraburi, Thailand. 20 pp.

Mabberley, D.J. & Sing, A.M., 1995. Meliaceae. Azadirachta. In: Kalkman, C. et al. (Editors): Flora Malesiana, Series 1, Vol. 12(1). Foundation Flora Malesiana, Leiden, the Netherlands. pp. 341-343.

Read, M.D. & French, J.H. (Editors), 1993. Genetic improvement of neem: Strategies for the future. Winrock International Institute for Agricultural Research, F/FRED Project, Bangkok, Thailand. 194 pp.

Ruskin, F.R., 1992. Neem. A tree for solving global problems. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., United States. 141 pp.

Schmutterer, H. (Editor), 1995. The neem tree Azadirachta indica A. Juss. and other meliaceous plants: sources of natural products for integrated pest management, medicine and industry and other purposes. VCH, Weinheim, Germany. 696 pp.

Tewari, D.N., 1992. Monograph on neem. R.P. Singh Gahlot for International Book Distributors, Dehra Dun, India. 279 pp.

Tampubolon, A.P. & Alrasyid, H., 1989. The neem tree and its developmental prospects in rainfed zones in Indonesia. Duta Rimba 15(109-110): 9-12.

Author(s)

S. Ahmed & Salma Idris

Correct Citation of this Article

Ahmed, S. & Idris, S., 1997. Azadirachta indica A.H.L. Juss.. In: Faridah Hanum, I & van der Maesen, L.J.G. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 11: Auxiliary plants. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.