Record Number

2997

PROSEA Handbook Number

11: Auxiliary plants

Taxon

Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pavon) Oken

Protologue

Allg. Naturgesch. 3(2): 1098 (1841).

Family

BORAGINACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = c. 72

Synonyms

Cerdana alliodora Ruiz & Pavon (1799), Cordia cerdana (Ruiz & Pavon) Roemer & Schultes (1819), Lithocardium alliodorum (Ruiz & Pavon) Kuntze (1891).

Vernacular Names

Cordia (general and trade name in the Americas), salmwood (trade name in the United Kingdom) (En). Spanish elm (Am). Bois soumis, chêne caparo, bois de rose (Fr). Laurel, cypre, capa prieto (Sp).

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Cordia alliodora is indigenous to dry and wet forest from Mexico and the Antilles to Brazil and Bolivia. It is now widely distributed in tropical America from northern Argentina to central Mexico and in the Caribbean islands. It has been introduced to Africa, Asia (Nepal, Sabah and Sri Lanka) and the Pacific region (Hawaii, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu).

Uses

Cordia alliodora produces high quality timber widely used where it occurs naturally. Because of its tall, straight stem, self-pruning habit and compact crown, combined with the ease with which it regenerates naturally on cleared sites, it is commonly grown in association with many agricultural crops and in numerous agroforestry systems, e.g. as shade tree in coffee and cocoa plantations and in pastures, often in combination with Erythrina poeppigiana (Walpers) O.F. Cook.

Its leaves and seeds have medicinal properties, the fruits are edible, if not very tasty, and its flowers are known to bee-keepers as a major source of nectar. The tree is planted as an ornamental because of its abundant, attractive, white, fragrant flowers.

The wood is used in construction, e.g. for doors, window frames, panelling, flooring, and for furniture, cabinet work, turnery, carving, scientific instruments, boats (including bridge decking), oars, sleepers, veneer, fuelwood and charcoal.

Its leaves and seeds have medicinal properties, the fruits are edible, if not very tasty, and its flowers are known to bee-keepers as a major source of nectar. The tree is planted as an ornamental because of its abundant, attractive, white, fragrant flowers.

The wood is used in construction, e.g. for doors, window frames, panelling, flooring, and for furniture, cabinet work, turnery, carving, scientific instruments, boats (including bridge decking), oars, sleepers, veneer, fuelwood and charcoal.

Properties

Wood of Cordia alliodora is easy to season and work and produces an attractive finish (pale golden-brown to brown with darker streaks). It has dimensional stability when dry, satisfactory mechanical characteristics, and is moderately durable to fungus attack with good resistance to termites. Basic density of the wood shows wide variation, 380—520 kg/m3 for natural forest samples from Central America. In Costa Rica, where it is found from tropical dry to tropical wet forest, basic density varies from 380—620 kg/m3 in naturally regenerated trees. Trees grown under drier conditions have the highest values. The density of the wood of plantation-grown trees in Vanuatu ranges from 270—530 kg/m3.

The weight of 1000 seeds is 15—50 g.

The weight of 1000 seeds is 15—50 g.

Description

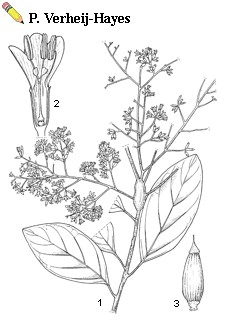

A large tree, up to 25(—40) m tall, with or without buttresses. Bark of young trees smooth and greenish, becoming greenish-black and sometimes narrowly fissured with age. Twigs stellate-pubescent when young, ending in obovoid ant domatia. Leaves alternate, simple, deciduous, stellate-pubescent; petiole 0.5—3.5 cm long; blade elliptical to slightly obovate, up to 20.5 cm x 8.5 cm, glabrous to densely stellate-pubescent. Inflorescence terminal, usually arising from an obovoid ant domatium, paniculate, up to 25(—30) cm broad, branches usually densely stellate-pubescent; pedicel up to 1.5 mm long; flowers many, about 1 cm long and wide, white; calyx tubular, 4—6 mm long, grey-green, 10(—12)-ribbed, (4—)5(—6)-toothed, densely stellate hairy; corolla tubular, (4—)5(—6)-lobed, up to 14 mm long, white, tube up to 8.5 mm long, lobes oblong and rounded, spreading, up to 8.5 mm long; stamens (4—)5(—6), erect, white, lower part connate with corolla; pistil with 2-forked style, each fork ending in 2, clavate stigma lobes. Fruit an ellipsoid nutlet, 4.5—8 mm x 1—2.5 mm, completely enveloped by the persistent corolla and calyx, the wall thin and fibrous. Seedling with epigeal germination.

Image

| Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pavon) Oken - 1, flowering branch; 2, vertical section through flower; 3, fruit |

Growth and Development

Seedlings develop a strong taproot. Later, spreading roots also develop which may grow into buttresses. Flowering may start when the trees are only 2 years old, but more commonly between 5—10 years after planting. Time of flowering and maturation of the fruit varies with locality; in Panama, flowering starts at the onset of the dry season. Lepidoptera are generally responsible for pollination. The mature fruit is shed with the withered flower still attached, which acts as a parachute during fruit fall, possibly assisting wind dispersal.

The bole is generally straight and cylindrical and often clear of branches 50—60% of the total tree height, even in open, uncrowded conditions.

The bole is generally straight and cylindrical and often clear of branches 50—60% of the total tree height, even in open, uncrowded conditions.

Other Botanical Information

The species is often incorrectly referred to as Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pavon) Cham. The genus contains about 300, mostly neotropical species and includes many useful timbers and some ornamentals with vivid, orange-red flowers. The flowers of Cordia alliodora vary from short-styled to forms with the stigma and anthers borne at about the same height, but individual plants have a constant ratio of anther and stigma height. The extent to which ant domatia are formed varies throughout the natural range. Domatia are is most prominent in Central America and north-western South America and almost absent in the West Indies and southern South America.

The crushed leaves and the inner bark have an odour of garlic ('alliodora').

The crushed leaves and the inner bark have an odour of garlic ('alliodora').

Ecology

Cordia alliodora is a pioneer plant, found in a wide range of habitats from sea level up to 1000(—2000) m. Optimal growth occurs where mean annual rainfall exceeds 2000 mm and the mean annual temperature is about 24°C. It is also common in drier areas with only 750 mm rainfall, but growth is slower and form of stem and crown poorer. It is a strong light-demander that readily colonizes exposed soils. Plantations of Cordia alliodora exposed to hurricanes and cyclones have shown above-average resistance to stem break and wind throw.

A range of soil types is tolerated. Fertile, freely-drained conditions are preferred. Growth on degraded soils and on sites with poor drainage is reduced. Cordia alliodora is particularly suitable for calcareous soils in the more humid tropics.

A range of soil types is tolerated. Fertile, freely-drained conditions are preferred. Growth on degraded soils and on sites with poor drainage is reduced. Cordia alliodora is particularly suitable for calcareous soils in the more humid tropics.

Propagation and planting

Cordia alliodora is readily propagated by seed or by stem cuttings. Timing of seed collection is important to ensure a high germination rate, generally up to 80%. Shaking of branches to allow mature seed with a high viability to drop is the best method. Viability of fresh seed decreases rapidly under natural conditions; dried to below 10% moisture it may be stored at 2°C for up to 10 years. Seed germinates in 5—20 days.

Vegetative propagation is possible. Stumps are the type of planting stock generally used due to the ease and cheapness of the technique and the robust planting material produced. Seedlings, however, are known to have a more rapid early growth and may be used in cases where rapid canopy closure is required. Direct sowing and wildlings are sometimes used in plantation establishment, although more intense weed control is then generally necessary. Choice of provenance is important.

In plantations a planting density of 4—5 m x 4—5 m is recommended. If a narrower spacing is used, thinning after 3—4 years is needed. In agroforestry spacing is adjusted to the associated crops. In coffee plantations in Costa Rica the optimum density of Cordia alliodora appears to be 100 mature trees/ha. The number of trees counted in agroforestry plots in Costa Rica ranges from 70—290/ha. Diameter increment in these plots was related to the associated crops and increased in the order pasture, sugar cane, coffee and cocoa.

Vegetative propagation is possible. Stumps are the type of planting stock generally used due to the ease and cheapness of the technique and the robust planting material produced. Seedlings, however, are known to have a more rapid early growth and may be used in cases where rapid canopy closure is required. Direct sowing and wildlings are sometimes used in plantation establishment, although more intense weed control is then generally necessary. Choice of provenance is important.

In plantations a planting density of 4—5 m x 4—5 m is recommended. If a narrower spacing is used, thinning after 3—4 years is needed. In agroforestry spacing is adjusted to the associated crops. In coffee plantations in Costa Rica the optimum density of Cordia alliodora appears to be 100 mature trees/ha. The number of trees counted in agroforestry plots in Costa Rica ranges from 70—290/ha. Diameter increment in these plots was related to the associated crops and increased in the order pasture, sugar cane, coffee and cocoa.

Husbandry

Regular weeding is crucial in the early stages of establishment. Organic matter accumulation in a cocoa plantation in Costa Rica with Cordia alliodora planted at 6 m x 6 m amounted to 87—110 t/ha in 10 years and the trees had a mean annual increment of 7.4 m3/ha. Cordia alliodora reduces the yield of cocoa, but the income generated from the timber compensates for this yield reduction.

Farmers in Central and South America rely mostly on natural regeneration of Cordia alliodora for shade trees, but increased use of herbicides may reduce the number of regenerating trees. Young to middle-aged trees coppice readily and suckers are sometimes abundant.

Farmers in Central and South America rely mostly on natural regeneration of Cordia alliodora for shade trees, but increased use of herbicides may reduce the number of regenerating trees. Young to middle-aged trees coppice readily and suckers are sometimes abundant.

Diseases and Pests

The rust fungus Puccinia cordiae is economically damaging to Cordia alliodora in its natural range. Other diseases noted to cause damage are a root disease caused by Phellinus noxius and a stem canker caused by Corticium salmonicolor in Vanuatu.

Yield

On suitable sites, with good management, annual growth of 2 m in height and 2 cm in diameter may be obtained during the first 10 years. Dimensions of 30—40 m height and 40—55 cm diameter at breast height are predicted for rotations of 20—25 years. In a 34-year-old plantation the mean annual increment of the Cordia alliodora trees was 8.8—20.3 m3/ha; however, up to 36% of this volume was lost due to buttresses, stem irregularities, heart rot, forking, and inefficient wood extraction.

Genetic Resources

Wide variation in morphology and performance is observed in the natural populations of Cordia alliodora. Provenance trials in Central America revealed that germination is more rapid and seedling growth faster for provenances from the Pacific watershed which experience a more pronounced dry season. However, growth rates of Atlantic provenances are superior within two years after planting, after initial slow development.

Breeding

The results of provenance trials are stimulating increased activities in the field of selection and breeding, e.g. in Vanuatu. Cordia alliodora is known to have a high degree of self-incompatibility. Other Cordia species are known to be either dioecious or heterostylous with associated self-incompatibility.

Prospects

The use of Cordia alliodora in exotic plantings and agroforestry shows promise due to its rapid growth, good stem form and fine wood. Its success in Central America bodes for good in South-East Asia. Further research on its use in silvopastoral systems is needed, especially with regard to resistance to trampling. The relation between wood quality, growth and provenance also needs to be evaluated further.

Literature

Fassbender, H.W., Beer, J., Heuveldop, J., Imbach, A., Enríquez, G. & Bonnemann, A., 1991. Ten year balances of organic matter and nutrients in agroforestry systems at CATIE, Costa Rica. In: Jarvis, P.G. (Editor): Agroforestry: principles and practice. Proceedings of an international conference, held at the University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom, 23-28 July 1989. Forest Ecology and Management 45(1-4): 173-183.

Greaves, A. & McCarter, P.S., 1990. Cordia alliodora. A promising tree for tropical agroforestry. Tropical Forestry Papers 22, Oxford Forestry Institute, Department of Plant Science, University of Oxford, United Kingdom. 37 pp.

Johnson, P. & Morales, R., 1972. A review of Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) Oken. Turrialba 22(2): 210-220.

Miller, J.S., 1988. A revised treatment of Boraginaceae for Panama. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 75: 456-521.

Neil, P.E., 1988. Root disease (Phellinus noxius (Corner) G.H. Cunn.) of Cordia alliodora in Vanuatu. Commonwealth Forestry Review 67(4): 361-372.

Sommariba, E.J. & Beer, J.W., 1987. Dimensions, volumes and growth of Cordia alliodora in agroforestry systems. Forest Ecology and Management 18(2): 113-126.

Greaves, A. & McCarter, P.S., 1990. Cordia alliodora. A promising tree for tropical agroforestry. Tropical Forestry Papers 22, Oxford Forestry Institute, Department of Plant Science, University of Oxford, United Kingdom. 37 pp.

Johnson, P. & Morales, R., 1972. A review of Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) Oken. Turrialba 22(2): 210-220.

Miller, J.S., 1988. A revised treatment of Boraginaceae for Panama. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 75: 456-521.

Neil, P.E., 1988. Root disease (Phellinus noxius (Corner) G.H. Cunn.) of Cordia alliodora in Vanuatu. Commonwealth Forestry Review 67(4): 361-372.

Sommariba, E.J. & Beer, J.W., 1987. Dimensions, volumes and growth of Cordia alliodora in agroforestry systems. Forest Ecology and Management 18(2): 113-126.

Author(s)

P.E. Neil & A.C.J. van Leeuwen

Correct Citation of this Article

Neil, P.E. & van Leeuwen, A.C.J., 1997. Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pavon) Oken. In: Faridah Hanum, I & van der Maesen, L.J.G. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 11: Auxiliary plants. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.