Record Number

3245

PROSEA Handbook Number

9: Plants yielding non-seed carbohydrates

Taxon

Xanthosoma Schott

Protologue

Melet. bot.: 19 (1832).

Family

ARACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

x = 12, 13; 2n = 26 (Xanthosoma nigrum, Xanthosoma sagittifolium)

Major Taxa and Synonyms

Major species and synonyms

— Xanthosoma nigrum (Vell.) Mansfeld, Verzeichnis: 549 (1959), synonyms: Arum nigrum Vell. (1827), Xanthosoma violaceum Schott (1853), Xanthosoma ianthinum K. Koch (1854).

— Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) Schott, Melet. bot.: 19 (1832) (sagittaefolium), synonyms: Arum sagittaefolium L. (1753), Arum xanthorrhizon Jacquin (1797), Xanthosoma xanthorrhizon (Jacquin) Koch (1856).

— Xanthosoma nigrum (Vell.) Mansfeld, Verzeichnis: 549 (1959), synonyms: Arum nigrum Vell. (1827), Xanthosoma violaceum Schott (1853), Xanthosoma ianthinum K. Koch (1854).

— Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) Schott, Melet. bot.: 19 (1832) (sagittaefolium), synonyms: Arum sagittaefolium L. (1753), Arum xanthorrhizon Jacquin (1797), Xanthosoma xanthorrhizon (Jacquin) Koch (1856).

Vernacular Names

General: Xanthosoma, cocoyam, tannia, yautia (En). Yautia, tanier, chou caraibe (Fr). Thailand: kradat (central).

— Xanthosoma nigrum: Indonesia: talas belitung (Indonesian), kimpul (Javanese, Sundanese), dilago gogomo (North Halmahera). Malaysia: keladi hitam, birah hitam, keladi kelamino. Papua New Guinea: kong kong taro. Philippines: cebu-yautia (Filipino), gabing-cebu (Tagalog), cebu-gabi (Bisaya). Laos: th'u:n. Thailand: kradat-dam (central). Vietnam: khoai s[as]p, ho[af]ng thu.

— Xanthosoma sagittifolium: New cocoyam (En).

— Xanthosoma nigrum: Indonesia: talas belitung (Indonesian), kimpul (Javanese, Sundanese), dilago gogomo (North Halmahera). Malaysia: keladi hitam, birah hitam, keladi kelamino. Papua New Guinea: kong kong taro. Philippines: cebu-yautia (Filipino), gabing-cebu (Tagalog), cebu-gabi (Bisaya). Laos: th'u:n. Thailand: kradat-dam (central). Vietnam: khoai s[as]p, ho[af]ng thu.

— Xanthosoma sagittifolium: New cocoyam (En).

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Xanthosoma originates from tropical America. Cultivars with edible tuberous rhizomes or leaves have been cultivated in the same area since ancient times and several cultivars later spread throughout the tropics. During the slave-trading era Xanthosoma was taken to Africa and in the 19th and early 20th Centuries it spread throughout Oceania and into Asia. Species often escape from cultivation and become naturalized. No reliable information on individual species is available because the genus lacks a thorough, critical taxonomic revision. Xanthosoma nigrum is commonly cultivated in tropical America (e.g. Puerto Rico, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Cuba, Panama, Guatemala and Venezuela) and occasionally in the other tropics. In South-East Asia, Xanthosoma nigrum is probably more commonly cultivated than Xanthosoma sagittifolium (e.g. in Java and the Philippines). In Malaysia, Xanthosoma sagittifolium seems to be more common.

Uses

In general, Xanthosoma species produce edible tuberous rhizomes (corms and cormels) and/or edible young leaves, and most species also have ornamental value. The tubers are washed and peeled before being further prepared. Some tubers are so hard that they require cooking before peeling. After being peeled, tubers are prepared in various ways; they may be boiled, baked, steamed, creamed, mashed or fried and are used in soups, chowders, stews and salads. They are also made into flour or meal for pastry which is stuffed with meat or other fillings, or to prepare puddings. In some taxa the main tubers (corms) are used (e.g. Xanthosoma atrovirens K. Koch & Bouché, Xanthosoma undipes (K. Koch & Bouché) K. Koch), in others the lateral tubers (cormels) (e.g. Xanthosoma nigrum, Xanthosoma sagittifolium). In Indonesia, cormels of Xanthosoma nigrum (which are rather slimy after being cooked) are not as popular as tubers of Colocasia esculenta L. Schott; in the Philippines, Xanthosoma nigrum is preferred. Young leaves of most cultivars are used as a vegetable; the leaves are cooked after the largest veins have been removed. In Indonesia, Xanthosoma sagittifolium is even primarily used as a leaf vegetable. In times of food scarcity, certainly tubers and leaves from wild or semi-wild (escaped) Xanthosoma species are also eaten. All parts (including debris) can also be used as animal feed. In traditional medicine in Malaysia, the large leaves of Xanthosoma nigrum are also used as blankets for patients with fever, because they are pleasantly cool and give temporary ease. Patients also bathe in a decoction of the plant. In the Philippines (Palawan), sap of the inflorescence is used to heal wounds and as an antidote for insect bites and stings.

Production and International Trade

Statistics on world production are always combined for Xanthosoma and Colocasia; they amounted to 5.6 million t in 1993. More than half of this production should certainly be ascribed to Colocasia, but since the 1950s, Xanthosoma has been gaining importance, in South-East Asia for example in Papua New Guinea. National and international markets are growing in response to demand from people who have moved from the countryside to urban centres, and from tropical homelands to industrialized countries. In the Caribbean, Xanthosoma is shipped between islands and to the United States and Europe. In Africa, Xanthosoma ranks third behind cassava and yam, but in Asia and Oceania it has only achieved minor crop status. Because of its remarkable general resistance to diseases and pests it often replaces other root and tuber crops and is becoming more popular as a reliable reserve food crop. In South-East Asia it is mainly a home garden crop for which no statistics are available.

Properties

In general, Xanthosoma (especially the yellow-fleshed types) is more nutritious than Colocasia and potato, but less nutritious than sweet potato, plantain and pumpkin.

Per 100 g edible portion, tubers of Xanthosoma nigrum contain approximately: water 58—68 g, ether extract 0.2—0.4 g, nitrogen 0.2—0.4 g, fibre 0.5—1.7 g, ash 0.9—1.2 g, Ca 6.7—18.5 mg, P 48—83 mg, Fe 0.3—4.5 mg, carotene 0.002—0.012 mg, niacin 0.6—0.8 mg, vitamin C 7—14 mg. Per 100 g edible portion, tubers of Xanthosoma sagittifolium contain approximately: water 70—77 g, protein 1.3—3.7 g, fat 0.2—0.4 g, carbohydrates 17—26 g, fibre 0.6—1.9 g, ash 0.6—1.3 g, carotene 2 mg, niacin 1 mg, vitamin C 96 mg and the energy value is about 560 kJ/100 g. The carbohydrates consist mainly of starch. The starch grains are relatively large, with an average diameter of 17—20 µm; the starch is less readily digested than Colocasia starch. Several cultivars may contain raphides (calcium oxalate crystals) in the leaves and the tubers, causing oral and intestinal irritation; the raphides can be made harmless by cooking. Coloured cultivars may contain saponins which can be released into the cooking water.

Per 100 g edible portion, leaves of Xanthosoma sagittifolium contain approximately: water 87 g, protein 2.5 g, fat 1 g, carbohydrates 5 g, fibre 2 g, ash 1 g, Ca 95 mg, P 388 mg, Fe 2 mg, vitamin C 37 mg and the energy value is about 140 kJ/100 g.

Per 100 g edible portion, tubers of Xanthosoma nigrum contain approximately: water 58—68 g, ether extract 0.2—0.4 g, nitrogen 0.2—0.4 g, fibre 0.5—1.7 g, ash 0.9—1.2 g, Ca 6.7—18.5 mg, P 48—83 mg, Fe 0.3—4.5 mg, carotene 0.002—0.012 mg, niacin 0.6—0.8 mg, vitamin C 7—14 mg. Per 100 g edible portion, tubers of Xanthosoma sagittifolium contain approximately: water 70—77 g, protein 1.3—3.7 g, fat 0.2—0.4 g, carbohydrates 17—26 g, fibre 0.6—1.9 g, ash 0.6—1.3 g, carotene 2 mg, niacin 1 mg, vitamin C 96 mg and the energy value is about 560 kJ/100 g. The carbohydrates consist mainly of starch. The starch grains are relatively large, with an average diameter of 17—20 µm; the starch is less readily digested than Colocasia starch. Several cultivars may contain raphides (calcium oxalate crystals) in the leaves and the tubers, causing oral and intestinal irritation; the raphides can be made harmless by cooking. Coloured cultivars may contain saponins which can be released into the cooking water.

Per 100 g edible portion, leaves of Xanthosoma sagittifolium contain approximately: water 87 g, protein 2.5 g, fat 1 g, carbohydrates 5 g, fibre 2 g, ash 1 g, Ca 95 mg, P 388 mg, Fe 2 mg, vitamin C 37 mg and the energy value is about 140 kJ/100 g.

Description

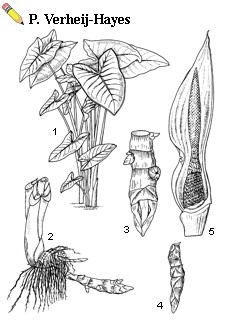

Erect, unarmed, laticiferous, perennial herbs, often arising from a tuberous rhizome. Root system fibrous and superficial. Rhizome with main part (corm) short and stout, or thick globose to cylindrical, forming lateral tuberous outgrowths (tubers or cormels). Stem varying from only a short, thick, underground rhizome, to a stem with a tall and thick aboveground part. Leaves with long, thick, subterete petiole, sheathing below; blade sagittate or hastate, or trisect to pedatisect; venation reticulate with secondary veins forming a zig-zag collecting vein between primary lateral veins. Inflorescence a spadix; peduncle solitary or aggregate, short to stout; spathe in 2 parts, the lower part tubular and persistent, the upper part (limb) spreading and quickly withering; spadix cylindrical, shorter than the spathe, divided into 3 parts: female below, male above, with a constricted sterile area in between; flowers unisexual, naked; male flower consisting of 4—6 stamens completely united into a truncate synandrium with marginal thecas; female flower with a 2—4-locular, many-ovuled ovary, a thick annular style more or less connate to the ovary, and a half-globose to discoid, 3—4-lobed stigma. Fruit a berry, crowned by the impressed stigma, many-seeded. Seed ovoid, grooved longitudinally.

— Xanthosoma nigrum. Vigorous plant, up to 2 m tall, lacking aboveground stem. Rhizome with a short, stout main part with numerous tubers; tubers rather smooth, purplish-grey, with purplish-red buds (eyes), flesh violet, red, pink, yellow or white. Petiole 30—100 cm long, violet to brown-green; blade sagittate-ovate, 20—100 cm 15—75 cm, dark green above with purple margin, pale green tinged with purple beneath, veins green to dark purple, 3 main ones prominent, central lobe 3—4 times longer than the 2 widely divergent, subtriangular basal lateral lobes. Inflorescence 30—60 cm long; peduncle 15—50 cm long; tube of spathe up to 10 cm 4 cm, violet or pale green outside, creamy within; limb oblong-lanceolate, 15—25 cm 6—7 cm, pale yellowish with longitudinal, purplish veins; spadix 15—25 cm long, female part 3—5 cm long, 1.5—2.5 cm in diameter, yellow-green, sterile part 3—5 cm long, pink-violet turning grey, male part 10—15 cm long, pale yellow, ending in a short obtuse tail. Fruit and seed unknown.

— Xanthosoma sagittifolium. Robust plant, up to 2 m or more tall, with thick subarborescent stem up to about 1 m long on the apex of which the leaves are borne. Rhizome with a thick globose to cylindrical main part with up to 10 or more tubers; tubers flask-shaped, 10—25 cm long, 10—15 cm in diameter, broadening towards the apex, pale brown outside, flesh white, pink or yellow. Petiole up to 1 m long; blade sagittate-ovate, 40—90 cm 40—60 cm, dark green above, glaucous below, central lobe acuminate and larger than the 2 subtriangular basal lobes, primary and secondary veins prominent. Inflorescence borne below the leaves, up to 4 at a node, but flowering is rare; peduncle up to 50 cm long; spathe up to 22 cm long, tubular part 8 cm, green, limb 14 cm, creamy; spadix up to 18 cm long, female part 2—3 cm, sterile part 3.5 cm, male part 11 cm, terminal appendage absent. Fruit and seed are rarely produced.

— Xanthosoma nigrum. Vigorous plant, up to 2 m tall, lacking aboveground stem. Rhizome with a short, stout main part with numerous tubers; tubers rather smooth, purplish-grey, with purplish-red buds (eyes), flesh violet, red, pink, yellow or white. Petiole 30—100 cm long, violet to brown-green; blade sagittate-ovate, 20—100 cm

— Xanthosoma sagittifolium. Robust plant, up to 2 m or more tall, with thick subarborescent stem up to about 1 m long on the apex of which the leaves are borne. Rhizome with a thick globose to cylindrical main part with up to 10 or more tubers; tubers flask-shaped, 10—25 cm long, 10—15 cm in diameter, broadening towards the apex, pale brown outside, flesh white, pink or yellow. Petiole up to 1 m long; blade sagittate-ovate, 40—90 cm

Image

| Xanthosoma nigrum (Vell.) Mansfeld - 1, habit; 2, lower plant part with roots and tuberous rhizomes; 3, large tuber; 4, small tuber; 5, inflorescence with spatha partly removed |

Growth and Development

Xanthosoma is a perennial herb with a continual turnover of leaves throughout its life, with the older ones dying as new ones appear. Often, however, it is grown as an annual, showing a growth cycle of 9—12 months. After a cormel is planted, shoot growth (mostly leaves) starts and increases rapidly, especially in the 5th and 6th months when the maximum leaf area index (LAI) of 4 and maximum dry matter weight of the leaves are reached; thereafter leaf number, leaf area and dry matter weight decrease until harvest. Dry matter accumulation in the corm starts 3 months after planting, increasing rapidly until the 7th month, after which it decreases slowly. Cormels start to develop 3 months after planting and increase in number until the 8th month. Dry matter accumulation in the cormels starts 4 months after planting, continuing until the 8th month, being greatest when shoot growth is decreasing. Flowering is relatively rare in most cultivars, but when it occurs it is usually early in the season. Flowers are protogynous and pollination is probably effected by flies. Fruits and seeds rarely develop in cultivars. At the end of the growing season the shoot may wither completely, leaving the corm and the cormels to perennate. In better climatological conditions the shoot may stay alive until the next growing season and if the cormels have not been harvested they start suckering.

Other Botanical Information

The taxonomy of Xanthosoma is confusing and speciation in the genus is not yet well understood. The genus comprises 40—60 species, but many 'species' have been distinguished on the basis of vegetative characteristics of dubious value. A critical taxonomic revision is urgently needed. At present the situation for the cultivated Xanthosoma is as follows:

— Xanthosoma brasiliense (Desf.) Engler. Indigenous in Central and South America, cultivated mainly in tropical America, but also in Tahiti, Hawaii and Micronesia. It is smaller than other Xanthosoma species, up to 40 cm tall, having characteristic hastate leaves with cuspidate apex and marked oblong basal lobes borne at right angles to the midrib. The tubers are small and although edible not usually eaten. It is only cultivated for its leaves which are eaten cooked as a vegetable.

— Xanthosoma nigrum (Vell.) Mansfeld. In South-East Asia, the most important species; in the literature better known by its synonymous name Xanthosoma violaceum. In Indonesia, 3 forms of Xanthosoma nigrum are distinguished based on leaf colour: completely green leaves (tuber white-fleshy), leaves with blue-violet petiole and main veins (tuber white-fleshy), and a form with its petioles streaked with green or blue (tuber yellow-fleshed containing more milky juice). The latter form is not fit to eat; its rhizome causes a severe itching of the mouth.

Well known cultivars are 'Kelly' and 'Dominicana'.

— Xanthosoma robustum Schott. Occurring wild and cultivated in Central America. Although with edible tubers, it is more important as ornamental because of its large size (stem up to 1.75 m long and 35 cm in diameter; leaves almost 2 m long).

— Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) Schott. Although originally described as a species from Central America, in practice it is now considered as a complex polymorphic species, cultivated pantropically for its edible tubers, comprising most or perhaps all cultivated forms of Xanthosoma, which is more a convenient agricultural unit than a taxonomic entity. It is an aggregate of the following difficult to distinguish species which are in effect mere cultivars and/or cultivar groups:

— Xanthosoma atrovirens K. Koch & Bouché. Originating from Venezuela, but cultivated in tropical America since pre-Columbian times and occasionally also elsewhere in the tropics. It is much favoured in Puerto Rico, Cuba and Jamaica. The plant is 1.5 m or more tall and has no aboveground stem. The corm is the major edible part because it is more tender than the tubers and its weight may attain 2.5 kg. The tubers are few, small and irregular and mainly used for planting. Corm and tubers are yellow-orange. Five botanical varieties have been distinguished based on differences in leaf form and colour. Well known cultivars are: 'Martinica Amarilla', 'Martinica' and 'Rascana'. In Puerto Rico, Xanthosoma atrovirens is very popular and the supply is never sufficient to meet the demand.

— Xanthosoma belophyllum (Willd.) Kunth. Originating from Venezuela and Colombia where it is also cultivated for its edible leaves. Four botanical varieties have been distinguished, based on leaf form and colour.

— Xanthosoma caracu K. Koch & Bouché. Only known from cultivation in tropical America, from Mexico and the Caribbean to northern South America. It is thought that most of the Caribbean cultivars belong to this group. It is a vigorous plant, 1.5—1.8 m tall, lacking an aboveground stem. Its tubers are numerous and large, club-shaped, grey-brown with white flesh. It never flowers. Well known cultivars are: 'Rolliza', 'Blanca Del Pais', 'Rascana', 'Viequera' and 'Inglesa'.

— Xanthosoma mafaffa Schott. Originating from northern South America but perhaps most important in West Africa where most cultivars are thought to belong to this species (e.g. in Nigeria only cultivars of Xanthosoma mafaffa occur). Three botanical varieties have been distinguished, based on differences in spathe and leaf form and colour. It is said to differ from Xanthosoma sagittifolium because of its characteristic divergent (not overlapping) basal leaf lobes and its cylindrical spadix (not tapering at the top).

— Xanthosoma undipes (K. Koch & Bouché) K. Koch (synonym: Xanthosoma jacquinii Schott). Originating from Mexico and much cultivated from Mexico and Florida to Venezuela and Ecuador. The plant has an aboveground stem, up to 2.5 m tall and 15 cm thick. The corm is the main edible part, with yellow-orange flesh that is acrid; it is made edible by slicing, drying and cooking. Tubers are rare and small. The plant has acrid milky sap and a foetid odour. In southern Colombia, an intoxicating drink called 'chicha' is prepared from ground, boiled and fermented tubers.

Xanthosoma and Colocasia are difficult to distinguish at first sight. Their main differences are: Xanthosoma has sagittate leaves, it cannot grow in flooded fields and its tubers store better; Colocasia has peltate leaves, can grow in flooded fields and its tubers do not store well.

— Xanthosoma brasiliense (Desf.) Engler. Indigenous in Central and South America, cultivated mainly in tropical America, but also in Tahiti, Hawaii and Micronesia. It is smaller than other Xanthosoma species, up to 40 cm tall, having characteristic hastate leaves with cuspidate apex and marked oblong basal lobes borne at right angles to the midrib. The tubers are small and although edible not usually eaten. It is only cultivated for its leaves which are eaten cooked as a vegetable.

— Xanthosoma nigrum (Vell.) Mansfeld. In South-East Asia, the most important species; in the literature better known by its synonymous name Xanthosoma violaceum. In Indonesia, 3 forms of Xanthosoma nigrum are distinguished based on leaf colour: completely green leaves (tuber white-fleshy), leaves with blue-violet petiole and main veins (tuber white-fleshy), and a form with its petioles streaked with green or blue (tuber yellow-fleshed containing more milky juice). The latter form is not fit to eat; its rhizome causes a severe itching of the mouth.

Well known cultivars are 'Kelly' and 'Dominicana'.

— Xanthosoma robustum Schott. Occurring wild and cultivated in Central America. Although with edible tubers, it is more important as ornamental because of its large size (stem up to 1.75 m long and 35 cm in diameter; leaves almost 2 m long).

— Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L.) Schott. Although originally described as a species from Central America, in practice it is now considered as a complex polymorphic species, cultivated pantropically for its edible tubers, comprising most or perhaps all cultivated forms of Xanthosoma, which is more a convenient agricultural unit than a taxonomic entity. It is an aggregate of the following difficult to distinguish species which are in effect mere cultivars and/or cultivar groups:

— Xanthosoma atrovirens K. Koch & Bouché. Originating from Venezuela, but cultivated in tropical America since pre-Columbian times and occasionally also elsewhere in the tropics. It is much favoured in Puerto Rico, Cuba and Jamaica. The plant is 1.5 m or more tall and has no aboveground stem. The corm is the major edible part because it is more tender than the tubers and its weight may attain 2.5 kg. The tubers are few, small and irregular and mainly used for planting. Corm and tubers are yellow-orange. Five botanical varieties have been distinguished based on differences in leaf form and colour. Well known cultivars are: 'Martinica Amarilla', 'Martinica' and 'Rascana'. In Puerto Rico, Xanthosoma atrovirens is very popular and the supply is never sufficient to meet the demand.

— Xanthosoma belophyllum (Willd.) Kunth. Originating from Venezuela and Colombia where it is also cultivated for its edible leaves. Four botanical varieties have been distinguished, based on leaf form and colour.

— Xanthosoma caracu K. Koch & Bouché. Only known from cultivation in tropical America, from Mexico and the Caribbean to northern South America. It is thought that most of the Caribbean cultivars belong to this group. It is a vigorous plant, 1.5—1.8 m tall, lacking an aboveground stem. Its tubers are numerous and large, club-shaped, grey-brown with white flesh. It never flowers. Well known cultivars are: 'Rolliza', 'Blanca Del Pais', 'Rascana', 'Viequera' and 'Inglesa'.

— Xanthosoma mafaffa Schott. Originating from northern South America but perhaps most important in West Africa where most cultivars are thought to belong to this species (e.g. in Nigeria only cultivars of Xanthosoma mafaffa occur). Three botanical varieties have been distinguished, based on differences in spathe and leaf form and colour. It is said to differ from Xanthosoma sagittifolium because of its characteristic divergent (not overlapping) basal leaf lobes and its cylindrical spadix (not tapering at the top).

— Xanthosoma undipes (K. Koch & Bouché) K. Koch (synonym: Xanthosoma jacquinii Schott). Originating from Mexico and much cultivated from Mexico and Florida to Venezuela and Ecuador. The plant has an aboveground stem, up to 2.5 m tall and 15 cm thick. The corm is the main edible part, with yellow-orange flesh that is acrid; it is made edible by slicing, drying and cooking. Tubers are rare and small. The plant has acrid milky sap and a foetid odour. In southern Colombia, an intoxicating drink called 'chicha' is prepared from ground, boiled and fermented tubers.

Xanthosoma and Colocasia are difficult to distinguish at first sight. Their main differences are: Xanthosoma has sagittate leaves, it cannot grow in flooded fields and its tubers store better; Colocasia has peltate leaves, can grow in flooded fields and its tubers do not store well.

Ecology

Xanthosoma is a plant of tropical rainforest regions, requiring average daily temperatures above 21°C, preferably between 25—29°C, being not tolerant of frost. Xanthosoma is a lowland crop but it is occasionally grown, usually with progressively reduced yields, up to 2000 m altitude. Average annual rainfall should be at least 1400 mm, but preferably 2000 mm, well distributed over the year, and soil moisture should be adequate. Unlike Colocasia, it does not withstand waterlogging. Under heavy shade, plants often survive as tubers, starting to grow only when more light becomes available. It grows best on deep, well-drained, fertile soils, within a pH range of 5.5—6.5. It tolerates light shade and slightly saline soils.

Propagation and planting

Xanthosoma is propagated vegetatively by planting the top of the corm (with petioles pruned to 15—30 cm length still attached), the whole corm, pieces of the corm (with at least 4 buds), tubers, suckers or by tissue culture. Top plantings give the highest yields and the larger the corm part the better the growth. Tissue culture is especially applied to obtain virus-free planting material; usually buds are excised from the primary corms or the tubers, disinfected, dried, treated with fungicides and planted in the nursery. After 2 months the young plants which have developed can be planted out in the field. Tissue culture starting from growing points is still experimental but is promising.

Land preparation varies from clearing in shifting cultivation to ploughing in permanent cropping systems. The best planting time is at the onset of the rainy season and planting on ridges makes harvesting easier. Planting distance varies from 0.6—1.8 m 0.6—1.8 m, 0.9 m 1.2 m being most common. Planting depth is about 5—7 cm and often 2—3 propagules are planted in the same hole. Xanthosoma is often planted as an intercrop in tree crops such as cacao, coffee, rubber, coconut, oil palm or banana because it yields better under 25—50% shade. Sometimes it serves as a shade crop for young plantings of cacao or coffee. In South-East Asia, Xanthosoma is primarily a home garden crop; in tropical America it is also cultivated on plantation scale.

Land preparation varies from clearing in shifting cultivation to ploughing in permanent cropping systems. The best planting time is at the onset of the rainy season and planting on ridges makes harvesting easier. Planting distance varies from 0.6—1.8 m

Husbandry

Weeding is essential in Xanthosoma as long as the crop does not shade the soil completely. Two weedings are usually sufficient, 1 and 2 months after planting respectively; weeding should be done carefully because the roots are easily damaged. In the Philippines, good results have been obtained with an integrated weeding system including ploughing between the rows 2 weeks after planting, weeding 3 weeks after planting and earthing up the plants after 5 weeks. Mulching, for example with coconut or banana leaves, also suppresses weeds and enhances yield. Chemical weed control is effective but is not recommended, being generally too expensive. Fertilizer is commonly applied and recommended quantities are 20—40 t organic manure per ha or NPK 110-45-110 kg/ha, divided over 2 gifts 2 and 6 months after planting. For good yields, water is essential and insufficient rainfall should preferably be complemented by irrigation. Inflorescences may appear 5—8 months after planting, depending on cultivar and growing conditions; they should be cut out.

Diseases and Pests

By comparison with Colocasia and many other root and tuber crops, Xanthosoma is remarkably resistant to diseases and pests. Bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas campestris may attack the leaves; it can be controlled by burning attacked plant material and by spraying with a copper solution. Reported fungal diseases causing rot of the tubers are soft rot (caused by Pythium spp.), root rot (caused by Corticium spp.) and sclerotium rot (caused by Sclerotium rolfsii). Control is possible by starting with disease-free planting material and by spraying with fungicides. Dasheen mosaic virus (DMV) is almost always present and in practice can only be controlled by starting with virus-free planting material (tissue culture) and by burning diseased plants.

Reported insect pests are the beetles Ligyrus ebenus attacking tubers in the field and Araecus fasciculatus attacking stored tubers; cotton leaf worm (Spodoptera litura) attacks the leaves; only chemical control is effective but biological control methods are promising. Nematodes (Meloidogyne spp. and Rotylenchus spp.) are not usually problematic, but crop rotation is recommended. Nutrient deficiencies may cause disease-like symptoms on the plants, e.g. stunted growth (shortage of NPK or Ca), necrotic leaf parts (shortage of K or Ca), orange discolouration on the leaves (shortage of Mg). Xanthosoma atrovirens is said to be less disease resistant than other species; Xanthosoma undipes is highly resistant to Pythium rot.

Reported insect pests are the beetles Ligyrus ebenus attacking tubers in the field and Araecus fasciculatus attacking stored tubers; cotton leaf worm (Spodoptera litura) attacks the leaves; only chemical control is effective but biological control methods are promising. Nematodes (Meloidogyne spp. and Rotylenchus spp.) are not usually problematic, but crop rotation is recommended. Nutrient deficiencies may cause disease-like symptoms on the plants, e.g. stunted growth (shortage of NPK or Ca), necrotic leaf parts (shortage of K or Ca), orange discolouration on the leaves (shortage of Mg). Xanthosoma atrovirens is said to be less disease resistant than other species; Xanthosoma undipes is highly resistant to Pythium rot.

Harvesting

Partial harvesting of tubers may start about 6 months after planting; for about 1.5 years, the largest tubers can be harvested every 3 months. Continuous harvesting discourages foliage production and encourages tuber formation; when the plants become older than 2 years, it is recommended to renew the crop. Harvesting of all tubers at the same time is usually done after 9—12 months; in seasonal climates the best moment of harvesting is at the end of the growing season when the leaves start to wither. Mechanical harvesting is possible, but often tubers are damaged too much. Harvesting of leaves may start about 6 weeks after planting and can continue whenever needed as long as the leaves show no yellowing at the edges.

Yield

Average annual yield of tubers varies with cultivar and growing conditions but for sole crops usually ranges between 12—20 t. In Papua New Guinea, yields of 15—25 t/ha per year have been reported. Best cultivars in Trinidad yielded up to 33 t/ha. As an intercrop between 6—8-year old coconut, tuber yield averaged 10 t/ha.

Handling After Harvest

Smallholders normally only harvest the amount of tubers needed for consumption, leaving the rest in the soil. Tubers can be stored well without losing eating quality for up to about 3 months under dry, cool, well-ventilated conditions. Harvested tubers are cleaned, peeled, cooked and prepared in various ways for direct consumption or, after grinding, prepared for commerce as deepfrozen pulp or as dried flour. At household level, flour is usually prepared from the tubers by peeling, slicing, drying in the sun and grinding.

Genetic Resources

Small germplasm collections of Xanthosoma are present in many countries where the crop is grown. Some major ones are: University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad; Agricultural Experiment Station, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico; Mayaguez Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Mayaguez, Puerto Rico; Agriculture Research and Education Center, University of Florida, Homestead, Florida, United States. In South-East Asia, some major collections are present in Malaysia (Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute, Kuala Lumpur, and University Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Selangor), Philippines (Philippine Root Crop Research and Training Center, several locations), Papua New Guinea (Department of Agriculture, Papua New Guinea University of Technology, Lae), Thailand (Department of Agronomy, Kasetsart University, Bangkok) and Vietnam (Institute for Experimental Biology, Ho Chi Minh City).

Breeding

Xanthosoma is a worthy target for improvement, e.g. to reduce acridity levels due to raphides, and to raise cultivars which are better adapted to adverse conditions of climate, soil and environment and better resistant to diseases and pests. Flowering can be induced by treating young plants with gibberellic acid.

Prospects

Although aroids are often considered as static or declining crops, this is not true for Xanthosoma, which is increasing in some Pacific Islands, in West Africa and elsewhere. Its easy propagation, its remarkable resistance to diseases and pests and high yields under difficult conditions make it an excellent staple crop. More germplasm collection, taxonomic and agronomical research are badly needed. In South-East Asia too it deserves much more scientific attention.

Literature

Kay, D.E., 1973. Crop and product digest No 2. Root crops. Tan(n)ia. The Tropical Products Institute, London, United Kingdom. pp. 160-167.

Morton, J.F., 1972. Cocoyams (Xanthosoma caracu, X. atrovirens and X. nigrum), ancient root and leaf vegetables, gaining in economic importance. Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society 85: 85-94.

Ochse, J.J. & Bakhuizen van den Brink, R.C., 1980. Vegetables of the Dutch East Indies. 3rd English edition (translation of 'Indische Groenten', 1931). Asher & Co., Amsterdam, the Netherlands. pp. 62-64.

O'Hair, S.K. & Asokan, M.P., 1986. Edible aroids: botany and horticulture. Horticultural Reviews 8(2): 43-99.

Onwueme, I.C., 1978. The tropical tuber crops. J. Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom. pp. 199-227.

Plucknett, D.L., 1976. Edible aroids. In: Simmonds, N.W. (Editor): Evolution of crop plants. Longmans, London, United Kingdom. pp. 10-12.

Purseglove, J.W., 1972. Tropical crops. Monocotyledons 1. Longman, London, United Kingdom. pp. 69-74.

Standley, P.C., 1944. Araceae. Xanthosoma. In: Woodson, R.E. & Schery, R.W. (Editors): Flora of Panama, Part 2(3). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 31(1): 38-41, 442-445.

Morton, J.F., 1972. Cocoyams (Xanthosoma caracu, X. atrovirens and X. nigrum), ancient root and leaf vegetables, gaining in economic importance. Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society 85: 85-94.

Ochse, J.J. & Bakhuizen van den Brink, R.C., 1980. Vegetables of the Dutch East Indies. 3rd English edition (translation of 'Indische Groenten', 1931). Asher & Co., Amsterdam, the Netherlands. pp. 62-64.

O'Hair, S.K. & Asokan, M.P., 1986. Edible aroids: botany and horticulture. Horticultural Reviews 8(2): 43-99.

Onwueme, I.C., 1978. The tropical tuber crops. J. Wiley & Sons, Chichester, United Kingdom. pp. 199-227.

Plucknett, D.L., 1976. Edible aroids. In: Simmonds, N.W. (Editor): Evolution of crop plants. Longmans, London, United Kingdom. pp. 10-12.

Purseglove, J.W., 1972. Tropical crops. Monocotyledons 1. Longman, London, United Kingdom. pp. 69-74.

Standley, P.C., 1944. Araceae. Xanthosoma. In: Woodson, R.E. & Schery, R.W. (Editors): Flora of Panama, Part 2(3). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 31(1): 38-41, 442-445.

Author(s)

P.C.M. Jansen & V. Premchand

Correct Citation of this Article

Jansen, P.C.M. & Premchand, V., 1996. Xanthosoma Schott. In: Flach, M. & Rumawas, F. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 9: Plants yielding non-seed carbohydrates. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.