Record Number

4480

PROSEA Handbook Number

5(2): Timber trees; Minor commercial timbers

Taxon

Octomeles Miq.

Protologue

Fl. Ind. Bat., Suppl. 1 (Prodr. Fl. Sum.): 336 (1861).

Family

DATISCACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

x = unknown; 2n = unknown

Trade Groups

Trade groups Binuang: lightweight hardwood, a single species, Octomeles sumatrana Miq., Fl. Ind. Bat., Suppl. 1 (Prodr. Fl. Sum.): 336 (1861), synonym: Octomeles moluccana Teijsm. & Binnend. ex Hassk. (1866).

Vernacular Names

Binuang. Indonesia: benuang, winuang, binuang bini (general). Papua New Guinea: erima, irima, ilimo (general). Philippines: bilus (Tagalog), barong (northern Luzon), barousan (southern Luzon).

Origin and Geographic Distribution

This monotypic genus occurs in Sumatra, Borneo, Sulawesi, the Moluccas, the Philippines, New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

Uses

The wood is used for several purposes, especially where strength is not important. The wood can only be used under cover for light furniture and joinery, interior finish, mouldings, wide shelves, louvred doors, coffin boards, large dugout canoes, rafts, sledges, jungle drums, concrete shuttering, packing, low-quality crates and boxes, buoys and fish-net floats, matchboxes, back and core veneer, firewood, chipboard and fibreboard, and for pulp and paper manufacture.

In Kalimantan the bark used to be combined with roots of mengkudu (Morinda citrifolia L.) and leaves of jirak (Symplocos spp.), to dye split rattan red. The inner bark contains a bitter purgative and a yellow dye. Young leaves are eaten as vegetable and the juice is used in local medicine to treat stomach-ache. Binuang trees are valued by local people as wild bees often nest in them.

In Kalimantan the bark used to be combined with roots of mengkudu (Morinda citrifolia L.) and leaves of jirak (Symplocos spp.), to dye split rattan red. The inner bark contains a bitter purgative and a yellow dye. Young leaves are eaten as vegetable and the juice is used in local medicine to treat stomach-ache. Binuang trees are valued by local people as wild bees often nest in them.

Production and International Trade

The export of binuang timber from Sabah in 1987 was 201 000 m3 of logs with a value of US$ 12.7 million, and in 1992 it was 95 000 m3 (21% as sawn timber, 79% as logs) with a total value of US$ 8.3 million (US$ 141/m3 for sawn timber, US$ 73/m3 for logs). In Papua New Guinea, binuang ("erima"") is a fairly important export timber and ranked in MEP (Minimum Export Price) group 3; saw logs fetched a minimum price of US$ 50/m3 in 1992. The import in Japan is about 1.5% of the total timber import from Papua New Guinea.

Properties

Binuang is a lightweight and comparatively soft hardwood. The heartwood is buff-coloured to pale brown, sometimes reddish-grey to brownish-grey or pinkish-brown, and moderately sharply defined from the 7.5—15 cm wide, almost white sapwood that has a faint greyish-yellow tinge. The density is (160—)270—400(—480) kg/m3 at 15% moisture content. The grain is usually interlocked, texture moderately coarse to coarse; quarter-sawn surfaces may show a broad-stripe figure.

At 12% moisture content, the modulus of rupture is (33.5—)41.5—55 N/mm2, modulus of elasticity (4700—)6200—8500 N/mm2, compression parallel to grain (22—)24—37.5 N/mm2, compression perpendicular to grain 2—4 N/mm2, shear 4—6 N/mm2, cleavage 29—64 N/mm radial and 39—57 N/mm tangential, Janka side hardness (990—)1490—1960 N and Janka end hardness (1340—)1960—2240 N. See also the table on wood properties.

The rates of shrinkage are moderate: from green to 12% moisture content 1.9% radial and 4.3% tangential, from green to oven dry 3.0% radial and 6.9% tangential. Considering its low density, binuang seasons slowly with rather severe degrade, especially in the zone between the heartwood and sapwood; degrade is caused by checking, splitting and distortion. Knots split moderately badly and staining is liable to occur. Boards 20 mm thick can be air dried in about 35 days to 18% moisture content, and boards 40 mm thick in about 90 days to 20% moisture content. Malaysian kiln schedule C is recommended for kiln drying, but even with this very mild schedule drying may be unsatisfactory. Once dry, binuang has good dimensional stability.

Binuang is easy to work with hand or machine tools. Because silica is absent or scarce, the wood has little dulling effect on cutting edges, but occasionally white deposits in the wood may chip planer knives. Sometimes severe woolly or fuzzy grain may be present on sawn surfaces. Ripsaws with 54 spring-set teeth and 25° hook cut the timber satisfactorily. Arrises tend to chip and the cutting angle has to be reduced to 20° to minimize picking-up in planing; sharp knives are particularly necessary with a reduced cutting angle to avoid a woolly finish. End-grain tends to crumble in mortising and paring, and a poor finish is usually obtained in drilling and cross-cutting; adequate support is needed to prevent breaking away at the exit of tools used across the grain. Binuang stains and polishes satisfactorily and nails moderately well, but screw and nailholding characteristics are sometimes poor. Steam-bending properties are very poor. Gluing properties are good. The timber is easy to cut and peels readily to smooth, tight veneer of uniform thickness without any bolt conditioning. The veneer dries flat and split-free, but it is liable to stain. Presence of brittle heart may cause problems in chucking. Because of its drab appearance, the wood is considered to be more suitable as core veneer. The pulp is rated as excellent for paper making.

Binuang heartwood is rated as non-durable in contact with the ground or exposed to the weather under tropical conditions, and as very perishable. In temperate regions the heartwood is also rated as perishable; samples were all destroyed in about 4 years in graveyard tests. The wood is very susceptible to termite attack. Sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus attack and frequently attacked by ambrosia beetles. The heartwood is moderately resistant to preservative treatment and requires pressure treatment to obtain fair results. The sapwood is reported as permeable, i.e. it can be penetrated completely under pressure without difficulty, and can be impregnated with satisfactory results by the open-tank process.

The wood contains c. 61% holocellulose, 23—32% lignin, 14—24% pentosan, 1.1—1.5% ash and up to 0.2% silica. The solubility is 1.7—2.9% in alcohol-benzene, 0.2% in cold water, 2.6—3.6% in hot water and 15.1—16.1% in a 1% NaOH solution. The energy value is about 19 750 kJ/kg.

At 12% moisture content, the modulus of rupture is (33.5—)41.5—55 N/mm2, modulus of elasticity (4700—)6200—8500 N/mm2, compression parallel to grain (22—)24—37.5 N/mm2, compression perpendicular to grain 2—4 N/mm2, shear 4—6 N/mm2, cleavage 29—64 N/mm radial and 39—57 N/mm tangential, Janka side hardness (990—)1490—1960 N and Janka end hardness (1340—)1960—2240 N. See also the table on wood properties.

The rates of shrinkage are moderate: from green to 12% moisture content 1.9% radial and 4.3% tangential, from green to oven dry 3.0% radial and 6.9% tangential. Considering its low density, binuang seasons slowly with rather severe degrade, especially in the zone between the heartwood and sapwood; degrade is caused by checking, splitting and distortion. Knots split moderately badly and staining is liable to occur. Boards 20 mm thick can be air dried in about 35 days to 18% moisture content, and boards 40 mm thick in about 90 days to 20% moisture content. Malaysian kiln schedule C is recommended for kiln drying, but even with this very mild schedule drying may be unsatisfactory. Once dry, binuang has good dimensional stability.

Binuang is easy to work with hand or machine tools. Because silica is absent or scarce, the wood has little dulling effect on cutting edges, but occasionally white deposits in the wood may chip planer knives. Sometimes severe woolly or fuzzy grain may be present on sawn surfaces. Ripsaws with 54 spring-set teeth and 25° hook cut the timber satisfactorily. Arrises tend to chip and the cutting angle has to be reduced to 20° to minimize picking-up in planing; sharp knives are particularly necessary with a reduced cutting angle to avoid a woolly finish. End-grain tends to crumble in mortising and paring, and a poor finish is usually obtained in drilling and cross-cutting; adequate support is needed to prevent breaking away at the exit of tools used across the grain. Binuang stains and polishes satisfactorily and nails moderately well, but screw and nailholding characteristics are sometimes poor. Steam-bending properties are very poor. Gluing properties are good. The timber is easy to cut and peels readily to smooth, tight veneer of uniform thickness without any bolt conditioning. The veneer dries flat and split-free, but it is liable to stain. Presence of brittle heart may cause problems in chucking. Because of its drab appearance, the wood is considered to be more suitable as core veneer. The pulp is rated as excellent for paper making.

Binuang heartwood is rated as non-durable in contact with the ground or exposed to the weather under tropical conditions, and as very perishable. In temperate regions the heartwood is also rated as perishable; samples were all destroyed in about 4 years in graveyard tests. The wood is very susceptible to termite attack. Sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus attack and frequently attacked by ambrosia beetles. The heartwood is moderately resistant to preservative treatment and requires pressure treatment to obtain fair results. The sapwood is reported as permeable, i.e. it can be penetrated completely under pressure without difficulty, and can be impregnated with satisfactory results by the open-tank process.

The wood contains c. 61% holocellulose, 23—32% lignin, 14—24% pentosan, 1.1—1.5% ash and up to 0.2% silica. The solubility is 1.7—2.9% in alcohol-benzene, 0.2% in cold water, 2.6—3.6% in hot water and 15.1—16.1% in a 1% NaOH solution. The energy value is about 19 750 kJ/kg.

Description

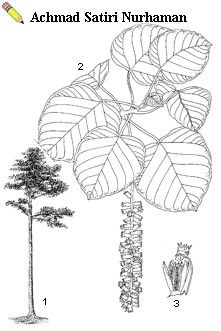

Large to very large dioecious evergreen trees up to 60(—75) m tall; bole cylindrical, straight, branchless for up to 30(—40) m, up to 250(—400) cm in diameter, with prominent buttresses up to 6 m high; bark surface fissured or irregularly cracked, often pustular, grey to grey-brown, inner bark fibrous, yellowish but rapidly turning brown on exposure, without exudate; crown open, pagoda-like with whorled branches when young, semi-globular when mature; twigs sharply 3-angled. Leaves arranged spirally, simple and entire, thin, roundish cordate, 12—30 cm 6—23 cm, acuminate, with 5—7(—9) palmate veins, minutely scaly and below with large domatial glands in the axils of the main veins; petiole 6—30 cm long; stipules absent. Flowers unisexual, actinomorphic, sessile, 5—8-merous, green, in solitary axillary spikes. Male inflorescence 20—60 cm long; flowers campanulate, 4—5 mm 5 mm, petals with an incurved appendage, anthers kidney-shaped. Female inflorescence 8—12 cm long; flowers c. 5 mm long, calyx campanulate, petals absent, ovary inferior, 1-celled, with 3—8 parietal placentae and many ovules, styles 5—8, inserted on the throat of the calyx tube, stigma capitate. Infructescence 15—40 cm long, on a 10—20 cm long peduncle. Fruit a barrel-shaped capsule, splitting from the top downwards, 12 mm long. Seeds many, spindle-shaped, c. 1 mm 0.2 mm.

Image

| Octomeles sumatrana Miq. – 1, tree habit; 2, twig with female inflorescence; 3, dehisced fruit. |

Wood Anatomy

— Macroscopic characters:

Heartwood pale brown, yellowish-brown to reddish-grey or brownish-grey, sometimes with pink tinge, moderately distinctly demarcated from the almost white to yellowish-white sapwood. Grain usually interlocked, sometimes straight. Texture moderately coarse to coarse; quarter-sawn surfaces lustrous and with broad stripes; wood without taste and odour, but green or wetted wood sometimes with foetid odour. Growth rings indistinct or absent; vessels visible to the naked eye, tyloses occasionally present; parenchyma indistinct; rays distinct to the naked eye; ripple marks absent.

— Microscopic characters:

Growth rings, if present, marked by narrow marginal parenchyma bands. Vessels diffuse, (1—)2—4(—7)/mm2, solitary and in radial multiples of 2—3, round to oval, average tangential diameter 140—230 µm; perforation plates simple; intervessel pits alternate, polygonal, 6—9 µm; vessel-ray pits with strongly reduced borders, large and gash-like to oval; tyloses occasionally present. Fibres 900—1600(—2000) µm long, non-septate, thin-walled (walls 3—5 µm thick), with minutely bordered to simple pits confined to the radial walls. Paratracheal parenchyma vasicentric or unilateral, in narrow (1—2 cells wide) sheaths or caps; apotracheal parenchyma usually absent, but occasionally marginal parenchyma bands present, in 2—4(—8)-celled strands. Rays 3—5/mm, (1—)2—5-seriate, 7—50 cells and up to 1800 µm high, heterocellular with 1—2 rows of upright or square marginal cells (Kribs type heterogeneous II and III). Crystals absent; reddish gummy substance and/or granular contents sometimes present in ray cells. Silica absent. Intercellular canals absent.

Heartwood pale brown, yellowish-brown to reddish-grey or brownish-grey, sometimes with pink tinge, moderately distinctly demarcated from the almost white to yellowish-white sapwood. Grain usually interlocked, sometimes straight. Texture moderately coarse to coarse; quarter-sawn surfaces lustrous and with broad stripes; wood without taste and odour, but green or wetted wood sometimes with foetid odour. Growth rings indistinct or absent; vessels visible to the naked eye, tyloses occasionally present; parenchyma indistinct; rays distinct to the naked eye; ripple marks absent.

— Microscopic characters:

Growth rings, if present, marked by narrow marginal parenchyma bands. Vessels diffuse, (1—)2—4(—7)/mm2, solitary and in radial multiples of 2—3, round to oval, average tangential diameter 140—230 µm; perforation plates simple; intervessel pits alternate, polygonal, 6—9 µm; vessel-ray pits with strongly reduced borders, large and gash-like to oval; tyloses occasionally present. Fibres 900—1600(—2000) µm long, non-septate, thin-walled (walls 3—5 µm thick), with minutely bordered to simple pits confined to the radial walls. Paratracheal parenchyma vasicentric or unilateral, in narrow (1—2 cells wide) sheaths or caps; apotracheal parenchyma usually absent, but occasionally marginal parenchyma bands present, in 2—4(—8)-celled strands. Rays 3—5/mm, (1—)2—5-seriate, 7—50 cells and up to 1800 µm high, heterocellular with 1—2 rows of upright or square marginal cells (Kribs type heterogeneous II and III). Crystals absent; reddish gummy substance and/or granular contents sometimes present in ray cells. Silica absent. Intercellular canals absent.

Growth and Development

Binuang is very fast growing. In trial plantations in the Solomon Islands, 4.5-year-old trees had an average height of 16 m and an average diameter of 21 cm. In Sabah, trees reached a height of 10 m 2.5 years after planting. For a 4-year-old binuang tree planted on volcanic soils in Bogor (West Java) a height of 25 m and a diameter of 47 cm have even been reported. Trees can attain 48 m height and 105 cm in diameter in 60 years.

The tree architecture is according to Massart's model, with an orthotropic, monopodial trunk having rhythmic growth and consequently producing regular tiers of plagiotropic branches.

The tree architecture is according to Massart's model, with an orthotropic, monopodial trunk having rhythmic growth and consequently producing regular tiers of plagiotropic branches.

Other Botanical Information

The Datiscaceae form a small family of only 4 species. The only other South-East Asian representative is Tetrameles nudiflora R.Br., a deciduous tree with hairy leaves and 4—5-merous flowers and by contrast it occurs only in slightly seasonal climates. The best field characteristics to identify binuang are the light-coloured bole, the nearly horizontal branches in young trees, and the form, texture and venation of the leaves.

Binuang trees often have bee nests attached to the branches.

Binuang trees often have bee nests attached to the branches.

Ecology

Binuang grows in lowland evergreen rain forest, up to 1000 m altitude. It is especially common in natural secondary and seral riverine alluvial forest where it is sometimes found in even-aged pure stands. Binuang is a pioneer of bare alluvial soil, binding the soil with a network of roots and thus improving the site. As such it precedes the successional stage of mixed lowland rain forest in which it may occur scattered. Binuang grows naturally in various other open locations such as on volcanic deposits and abandoned logging roads. In Sabah, binuang is frequently associated with kadam (Anthocephalus chinensis (Lamk) A. Rich. ex Walp.). In Papua New Guinea and New Britain, binuang occurs in habitats similar to those of kamarere (Eucalyptus deglupta Blume) with which it is sometimes associated. The riverine binuang forest is usually characterized by good drainage and only temporary flooding. The most important condition for growth of binuang appears to be an evenly distributed annual rainfall of at least 1500 mm.

Propagation and planting

Binuang can be propagated by seed. Once every 3—4 years fruit production is very abundant. The capsules can be collected when they begin to turn brown. They split upon drying and vigorous shaking is necessary to release the seeds. There are 11 500—20 000 dry seeds in one kg. Seed is susceptible to damage by fungi during transportation. The germination rate is variable but generally quite low, about 40%, and decreases rapidly with time, to 25% after 2 months and there is no germination at all after 3 months.

For sowing, seeds are mixed with fine river sand and sown in special trays which are kept moist under full shade. The seed must be sown thinly, to prevent dense clumps of seedlings. Damping-off can be prevented by good ventilation. Seedlings can be pricked out 5—6 weeks after sowing and are ready for planting after about 4 months when they are 15—20 cm tall. Different spacings have been tested, ranging from 2.4 m 2.4 m to 4.8 m 4.8 m. A spacing of 2.4 m 4.8 m seems most appropriate for plantation establishment. Binuang needs a fertile, deep soil for proper development.

For sowing, seeds are mixed with fine river sand and sown in special trays which are kept moist under full shade. The seed must be sown thinly, to prevent dense clumps of seedlings. Damping-off can be prevented by good ventilation. Seedlings can be pricked out 5—6 weeks after sowing and are ready for planting after about 4 months when they are 15—20 cm tall. Different spacings have been tested, ranging from 2.4 m

Silviculture and Management

Binuang is considered a true pioneer and establishes itself readily in open areas such as dry river beds, on volcanic deposits and abandoned logging roads, where light and freshly exposed soil can be found. It does not tolerate any shade. Rapid early growth and crown closure (1—1.5 years after planting) are advantageous characteristics in plantations as well as its good self-pruning capacity and freedom from serious pests. Survival after planting is generally high. In open stands herbaceous and woody climbers may cause considerable damage to binuang as they hang down in large masses from the horizontal branches and often completely smother the trees. These climbers must be weeded out or cut out. Apparently, binuang does not thrive in closed plantations and the spreading crown seems to suffer from branch contact with neighbouring trees. It is fairly resistant to fire. Trials with binuang have also been established outside the South-East Asian region, e.g. in Brazil.

Diseases and Pests

Brittle heart is a defect found in binuang logs. Characoma moths cause partial or complete defoliation and dieback. Unidentified shoot borers have also been observed, but did not cause serious damage. Trees with severely perforated leaves are very common, but usually recover well.

Harvesting

For the production of pulpwood, harvesting can start 4—5 years after planting, depending on the site conditions. No data are available on the rotation cycle of binuang harvested for timber, but a cycle of 30—40 years like that used for Anthocephalus chinensis, seems to be applicable for binuang as well. Boles from natural forest are usually obtainable in lengths of 21 m or more.

Yield

Thinned and unthinned plots in a natural regenerated stand in the Philippines displayed a mean annual increment of 46 and 36 m3/ha, respectively, over the period of 4—6 years after logging. For large-scale plantations in Indonesia the expected annual increment during a rotation of 30 years is 25—40 m3/ha.

Handling After Harvest

The wood deteriorates very rapidly and must be extracted from the forest is immediately. The timber has to be worked up soon after cutting and it should be treated within 2 days or be submerged in water. Immediately after sawing binuang has to be treated to prevent stain. The logs float in water and can be transported by river.

Genetic Resources

At present, a fair supply of Octomeles sumatrana is still available in the South-East Asian region, particularly in Irian Jaya and Papua New Guinea. There seems to be no immediate risk of genetic erosion as it occurs frequently and regenerates abundantly along rivers and in open low-lying locations in secondary forest. Plantations have been established to some extent in the Philippines and Papua New Guinea.

Prospects

Binuang merits attention as a plantation species, especially for the production of raw material for the manufacture of plywood and of pulp for paper making. It develops well in open areas and can be used for enrichment planting in logged-over forest and as a fast-growing species on low-lying alang-alang (Imperata cylindrica (L.) Raeuschel) grasslands. The development of silvicultural management techniques is a research priority.

Literature

Croft, J.R., 1978. Datiscaceae. In: Womersley, J.S. & Henty, E.E. (Editors): Handbooks of the flora of Papua New Guinea. Vol. 1. Melbourne University Press, Carlton. pp. 114-119.

Faustino Jr., D.M. & Bascug, E.M., 1977. Timber stand improvement of binuang (Octomeles sumatrana) in natural stands. Sylvatrop 2(2): 111-116.

Fenton, R., Roper, R.E. & Watt, G.R., 1977. Lowland tropical hardwoods. An annotated bibliography of selected species with plantation potential. Forest Research Institute New Zealand Forest Service, External Aid Division, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Wellington. pp. OS1-OS13.

Fundter, J.M. & Wisse, J.H., 1977. 40 belangrijke houtsoorten uit Indonesisch Nieuw Guinea (Irian Jaya) met de anatomische en technische kenmerken [40 important timber species from Indonesian New Guinea (Irian Jaya), with their anatomical and technical characteristics]. Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen 77-9. pp. 45-47.

Koopman, M.J.F. & Verhoef, L., 1938. Octomeles sumatrana Miq. (benoeang) en Tetrameles nudiflora R.Br. (winong) [Octomeles sumatrana Miq. (benuang) and Tetrameles nudiflora R. Br. (winong)]. Tectona 31: 777-790.

Malaysian Timber Industry Board, 1986. 100 Malaysian timbers. Kuala Lumpur. pp. 124-125.

Martawijaya, A., Kartasujana, I., Mandang, Y.I., Prawira, S.A. & Kadir, K., 1992. Indonesian wood atlas. Vol. 2. Forest Products Research and Development Centre, Bogor. pp. 19-24.

Pratiwi & Alrasjid, H., 1988. Prospect of binuang tree (Octomeles sumatrana Miq.) for timber estate. Duta Rimba 19(99/100): 29-33.

Shim, P.S., 1973. Octomeles sumatrana in plantation trials in Sabah. Malayan Forester 36: 16-21.

van Steenis, C.G.G.J., 1953. Datiscaceae. In: van Steenis, C.G.G.J. (Editor): Flora Malesiana. Ser. 1, Vol. 4. Noordhoff-Kolff n.v., Djakarta. pp. 382-387.

Faustino Jr., D.M. & Bascug, E.M., 1977. Timber stand improvement of binuang (Octomeles sumatrana) in natural stands. Sylvatrop 2(2): 111-116.

Fenton, R., Roper, R.E. & Watt, G.R., 1977. Lowland tropical hardwoods. An annotated bibliography of selected species with plantation potential. Forest Research Institute New Zealand Forest Service, External Aid Division, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Wellington. pp. OS1-OS13.

Fundter, J.M. & Wisse, J.H., 1977. 40 belangrijke houtsoorten uit Indonesisch Nieuw Guinea (Irian Jaya) met de anatomische en technische kenmerken [40 important timber species from Indonesian New Guinea (Irian Jaya), with their anatomical and technical characteristics]. Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen 77-9. pp. 45-47.

Koopman, M.J.F. & Verhoef, L., 1938. Octomeles sumatrana Miq. (benoeang) en Tetrameles nudiflora R.Br. (winong) [Octomeles sumatrana Miq. (benuang) and Tetrameles nudiflora R. Br. (winong)]. Tectona 31: 777-790.

Malaysian Timber Industry Board, 1986. 100 Malaysian timbers. Kuala Lumpur. pp. 124-125.

Martawijaya, A., Kartasujana, I., Mandang, Y.I., Prawira, S.A. & Kadir, K., 1992. Indonesian wood atlas. Vol. 2. Forest Products Research and Development Centre, Bogor. pp. 19-24.

Pratiwi & Alrasjid, H., 1988. Prospect of binuang tree (Octomeles sumatrana Miq.) for timber estate. Duta Rimba 19(99/100): 29-33.

Shim, P.S., 1973. Octomeles sumatrana in plantation trials in Sabah. Malayan Forester 36: 16-21.

van Steenis, C.G.G.J., 1953. Datiscaceae. In: van Steenis, C.G.G.J. (Editor): Flora Malesiana. Ser. 1, Vol. 4. Noordhoff-Kolff n.v., Djakarta. pp. 382-387.

Other Selected Sources

[12]All Nippon Checkers Corporation, 1989. Illustrated commercial foreign woods in Japan. Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo. 262 pp.

[60]Bolza, E. & Kloot, N.H., 1966. The mechanical properties of 81 New Guinea timbers. Technological Paper No 41. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 39 pp.

[69]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching. xviii + 369 pp.

[77]Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Sabah Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Sabah, Sandakan. xviii + 501 pp.

[96]Chudnoff, M., 1984. Tropical timbers of the world. Agricultural Handbook 607. USDA Forest Service, Washington, D.C. 464 pp.

[114]Dahms, K.-G., 1969. Neue Importholzkunde Teil II, Asien (12). Binuang (Octomeles sumatrana Miq., Familie der Datiscaceen) [New knowledge on imported timbers part II, Asia (12). Binuang (Octomeles sumatrana Miq., Datiscaceae family)]. Holz-Zentralblatt No 89: 1379.

[115]Dahms, K.-G., 1982. Asiatische, ozeanische und australische Exporthölzer [Asiatic, Pacific and Australian export timbers]. DRW-Verlag, Stuttgart. 304 pp.

[158]Farmer, R.H., 1972. A handbook of hardwoods. 2nd edition. Her Majesty's Stationary Office, London. 243 pp.

[164]Foreman, D.B., 1971. A check list of the vascular plants of Bougainville with descriptions of some common forest trees. Botany Bulletin No 5. Division of Botany, Department of Forests, Lae. 194 pp.

[216]HallT, F., Oldeman, R.A.A. & Tomlinson, P.B., 1978. Tropical trees and forests – an architectural analysis. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. 441 pp.

[218]Hardjowasono, M.S., 1942. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of fruits and seeds]. Korte mededelingen No 20. Bosbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 172 pp.

[255]International Union of Forestry Research Organizations, 1973. Veneer species of the world. Forest Products Laboratory, Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Madison. 150 pp.

[289]Keating, W.G. & Bolza, 1982. Characteristics, properties and uses of timbers. Vol. 1. South-East Asia, northern Australia and the Pacific. Inkata Press Proprietary Ltd., Melbourne, Sydney & London. 362 pp.

[297]Kingston, R.S.T. & Risdon, C.J.E., 1961. Shrinkage and density of Australian and other South-West Pacific woods. Technological Paper No 13. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 65 pp.

[330]Kraemer, J.H., 1951. Trees of the western Pacific region. Tri-State Offset Company, Cincinnatti. 436 pp.

[352]Lauricio, F.M. & Bellosillo, S.B., 1963/64. The mechanical and related properties of Philippine woods. Philippine Lumberman 10: 49–56.

[356]Lavers, G.M., 1983. The strenght properties of timber. 3rd edition, revised by G.L. Moore. Building Research Establishment. Department of Environment, Her Majesty's Stationary Office, London. 60 pp.

[393]Malaysian Timber Industry Board, 1984. Peraturan pemeringkatan kayu keras gergaji Malaysia [The Malaysian grading rules for sawn hardwood timber]. Ministry of Primary Industries, Kuala Lumpur. 109 pp.

[414]Meniado, J.A. et al., 1975–1981. Wood identification handbook for Philippine timbers. 2 volumes. Government Printing Office, Manila. 370 pp. & 186 pp.

[478]Paijmans, K., 1976. New Guinea vegetation. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam, Oxford, New York. 213 pp.

[489]Peekel, P.G., 1984. Flora of the Bismarck Archipelago for naturalists. Office of Forests, Division of Botany, Lae. 638 pp.

[527]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[592]South East Asia Lumber Producers' Association, 1980. Lesser known timber species of SEALPA countries. A review and summary presented to SEALPA from PNG subcommittee 'Lesser known species'. 140 pp.

[644]TNO Forest Products Research Institute, 1958. Algemeen rapport van Octomeles sumatrana Miq. [General report on Octomeles sumatrana Miq.]. TNO Report H-58-28, Delft. 4 pp. + 3 tables.

[695]Westphal, E. & Jansen, P.C.M. (Editors), 1989. Plant resources of South-East Asia. A selection. Pudoc, Wageningen. 322 pp.

[703]Whitmore, T.C., 1984. Tropical rainforest of the Far East. 2nd edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford. xvi + 352 pp.

[719]Womersley, J.S. & McAdam, J.B., 1957. The forests and forest conditions in the territories of Papua and New Guinea. Papua New Guinea Forest Service. Reprint of 1975. The Wilke Group, Zillmere. 62 pp.

[729]Working group on utilization of tropical woods, 1977. Properties of some Papua New Guinea woods relating with manufacturing processes I. Lumber processing of some East New Britain woods. Bulletin of the Government Forest Experiment Station No 292: 27–95.

[730]Working group on utilization of tropical woods, 1977. Properties of some Papua New Guinea woods relating with manufacturing processes II. Plywood, particleboard, fibreboard, pulp and charcoal from some East New Britain woods. Bulletin of the Government Forest Experiment Station No 292: 97—160.

[60]Bolza, E. & Kloot, N.H., 1966. The mechanical properties of 81 New Guinea timbers. Technological Paper No 41. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 39 pp.

[69]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching. xviii + 369 pp.

[77]Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Sabah Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Sabah, Sandakan. xviii + 501 pp.

[96]Chudnoff, M., 1984. Tropical timbers of the world. Agricultural Handbook 607. USDA Forest Service, Washington, D.C. 464 pp.

[114]Dahms, K.-G., 1969. Neue Importholzkunde Teil II, Asien (12). Binuang (Octomeles sumatrana Miq., Familie der Datiscaceen) [New knowledge on imported timbers part II, Asia (12). Binuang (Octomeles sumatrana Miq., Datiscaceae family)]. Holz-Zentralblatt No 89: 1379.

[115]Dahms, K.-G., 1982. Asiatische, ozeanische und australische Exporthölzer [Asiatic, Pacific and Australian export timbers]. DRW-Verlag, Stuttgart. 304 pp.

[158]Farmer, R.H., 1972. A handbook of hardwoods. 2nd edition. Her Majesty's Stationary Office, London. 243 pp.

[164]Foreman, D.B., 1971. A check list of the vascular plants of Bougainville with descriptions of some common forest trees. Botany Bulletin No 5. Division of Botany, Department of Forests, Lae. 194 pp.

[216]HallT, F., Oldeman, R.A.A. & Tomlinson, P.B., 1978. Tropical trees and forests – an architectural analysis. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. 441 pp.

[218]Hardjowasono, M.S., 1942. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of fruits and seeds]. Korte mededelingen No 20. Bosbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 172 pp.

[255]International Union of Forestry Research Organizations, 1973. Veneer species of the world. Forest Products Laboratory, Forest Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Madison. 150 pp.

[289]Keating, W.G. & Bolza, 1982. Characteristics, properties and uses of timbers. Vol. 1. South-East Asia, northern Australia and the Pacific. Inkata Press Proprietary Ltd., Melbourne, Sydney & London. 362 pp.

[297]Kingston, R.S.T. & Risdon, C.J.E., 1961. Shrinkage and density of Australian and other South-West Pacific woods. Technological Paper No 13. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 65 pp.

[330]Kraemer, J.H., 1951. Trees of the western Pacific region. Tri-State Offset Company, Cincinnatti. 436 pp.

[352]Lauricio, F.M. & Bellosillo, S.B., 1963/64. The mechanical and related properties of Philippine woods. Philippine Lumberman 10: 49–56.

[356]Lavers, G.M., 1983. The strenght properties of timber. 3rd edition, revised by G.L. Moore. Building Research Establishment. Department of Environment, Her Majesty's Stationary Office, London. 60 pp.

[393]Malaysian Timber Industry Board, 1984. Peraturan pemeringkatan kayu keras gergaji Malaysia [The Malaysian grading rules for sawn hardwood timber]. Ministry of Primary Industries, Kuala Lumpur. 109 pp.

[414]Meniado, J.A. et al., 1975–1981. Wood identification handbook for Philippine timbers. 2 volumes. Government Printing Office, Manila. 370 pp. & 186 pp.

[478]Paijmans, K., 1976. New Guinea vegetation. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam, Oxford, New York. 213 pp.

[489]Peekel, P.G., 1984. Flora of the Bismarck Archipelago for naturalists. Office of Forests, Division of Botany, Lae. 638 pp.

[527]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[592]South East Asia Lumber Producers' Association, 1980. Lesser known timber species of SEALPA countries. A review and summary presented to SEALPA from PNG subcommittee 'Lesser known species'. 140 pp.

[644]TNO Forest Products Research Institute, 1958. Algemeen rapport van Octomeles sumatrana Miq. [General report on Octomeles sumatrana Miq.]. TNO Report H-58-28, Delft. 4 pp. + 3 tables.

[695]Westphal, E. & Jansen, P.C.M. (Editors), 1989. Plant resources of South-East Asia. A selection. Pudoc, Wageningen. 322 pp.

[703]Whitmore, T.C., 1984. Tropical rainforest of the Far East. 2nd edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford. xvi + 352 pp.

[719]Womersley, J.S. & McAdam, J.B., 1957. The forests and forest conditions in the territories of Papua and New Guinea. Papua New Guinea Forest Service. Reprint of 1975. The Wilke Group, Zillmere. 62 pp.

[729]Working group on utilization of tropical woods, 1977. Properties of some Papua New Guinea woods relating with manufacturing processes I. Lumber processing of some East New Britain woods. Bulletin of the Government Forest Experiment Station No 292: 27–95.

[730]Working group on utilization of tropical woods, 1977. Properties of some Papua New Guinea woods relating with manufacturing processes II. Plywood, particleboard, fibreboard, pulp and charcoal from some East New Britain woods. Bulletin of the Government Forest Experiment Station No 292: 97—160.

Author(s)

J.W. Hildebrand (general part), E. Boer (general part), P.B. Laming (properties), J.M. Fundter (wood anatomy)

Correct Citation of this Article

Hildebrand, J.W., Boer, E., Laming, P.B. & Fundter, J.M., 1995. Octomeles Miq.. In: Lemmens, R.H.M.J., Soerianegara, I. and Wong, W.C. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 5(2): Timber trees; Minor commercial timbers. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.