Record Number

5593

PROSEA Handbook Number

5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers

Taxon

Hibiscus L.

Protologue

Sp. pl. 2: 693 (1753); Gen. pl., ed. 5: 310 (1754).

Family

MALVACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

x = 8, 9, 12, 18, 21; H. tiliaceus: 2n ? 86, 92, 2n = 96

Vernacular Names

Hibiscus, roselle, rose mallow (En). Roselle (Fr). Indonesia: baru, waru. Malaysia: baru, bebaru bulu (Peninsular), baru laut (Sarawak). Thailand: ehaba. Vietnam: d[aa]m b[uj]t, ph[uf] dung.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Hibiscus comprises about 275 species occurring in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, with only 3 of them in temperate zones. Within the Malesian region 43 species are found, of which a minority yields timber.

Uses

Although soft and comparatively weak, the wood of Hibiscus is quite attractive and used for local house building, interior trim, moulding, wagon frames, vehicle shafts, spokes and rims of wheels, gunstocks, household implements, tool handles, scabbards, musical instruments, picture frames, carving, package and fittings, toothpicks, matches and matchboxes, fencing and occasionally also for marquetry and barrel hoops. It has been reported to last very long in contact with water and has been applied for ship and boat building (frames and keels). The wood is also suitable for the manufacture of plywood, hardboard and probably also for that of paper. It yields a good firewood. The flexible branches have been used as fishing rods.

The bark of several timber-yielding species, notably from that of H. tiliaceus, can be used to manufacture a good quality rope which is also used for caulking boats. In Java the bark fibres are called "lulub waru"" and in southern Sumatra they are also used for plaiting mats. H. macrophyllus and H. tiliaceus have been used to reforest eroded land, the latter also as a shade tree, hedge or wind-break, especially along the seashore, and, because of its showy yellow flowers with a purple centre, also as an ornamental. The bark and leaves of H. tiliaceus are used medicinally, especially to relieve coughs, sore throats and tuberculosis.

The bark of several timber-yielding species, notably from that of H. tiliaceus, can be used to manufacture a good quality rope which is also used for caulking boats. In Java the bark fibres are called "lulub waru"" and in southern Sumatra they are also used for plaiting mats. H. macrophyllus and H. tiliaceus have been used to reforest eroded land, the latter also as a shade tree, hedge or wind-break, especially along the seashore, and, because of its showy yellow flowers with a purple centre, also as an ornamental. The bark and leaves of H. tiliaceus are used medicinally, especially to relieve coughs, sore throats and tuberculosis.

Production and International Trade

As the supply is very limited and sizes are small, Hibiscus wood is used on a local scale only; it may prove useful for specialty purposes.

Properties

Hibiscus yields a lightweight to medium-weight hardwood with a density of (335-)370-720 kg/m3 at 15% moisture content. Heartwood pale or dark yellow, brown, pale brown-grey or blue-grey with purplish tinge, grey-black, purple-black, sharply differentiated from the white or pale yellow, generally wide sapwood; grain straight, interlocked or alternating; texture fine to moderately fine, even; silver grain distinct. Growth rings indistinct to distinct indicated by colour differences or occasional marginal parenchyma; vessels moderately small to moderately large, solitary and in radial or occasionally tangential multiples of 2-4(-6) or in clusters, open; parenchyma moderately abundant, paratracheal vasicentric, and apotracheal diffuse-in-aggregates, variable in distinctness; rays extremely fine to medium-sized, distinct to the naked eye; ripple marks present and distinct; traumatic canals occasionally present.

Shrinkage of wood during seasoning is low in H. tiliaceus, moderate to high in H. campylosiphon. The wood seasons well but is highly susceptible to blue stain. It is soft to moderately hard, weak, but tough and elastic. It is easy to work and generally produces a smooth finish. The wood is non-durable when exposed to the weather or in contact with the ground although H. d'albertisii is reported durable. Under cover, the heartwood is resistant to dry-wood termites. The sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus.

Paper manufactured from H. tiliaceus pulp is of low quality as the fibres are short (0.7-1.3 mm) and is only suitable for wrapping paper. Acetone extracts from the leaves of H. tiliaceus showed antibacterial activity.

See also the tables on microscopic wood anatomy and wood properties.

Shrinkage of wood during seasoning is low in H. tiliaceus, moderate to high in H. campylosiphon. The wood seasons well but is highly susceptible to blue stain. It is soft to moderately hard, weak, but tough and elastic. It is easy to work and generally produces a smooth finish. The wood is non-durable when exposed to the weather or in contact with the ground although H. d'albertisii is reported durable. Under cover, the heartwood is resistant to dry-wood termites. The sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus.

Paper manufactured from H. tiliaceus pulp is of low quality as the fibres are short (0.7-1.3 mm) and is only suitable for wrapping paper. Acetone extracts from the leaves of H. tiliaceus showed antibacterial activity.

See also the tables on microscopic wood anatomy and wood properties.

Botany

Deciduous or evergreen, small to medium-sized trees up to 30 m tall, or shrubs or herbs; bole branchless for up to 12 m, up to 80 cm in diameter, sometimes with small buttresses; bark surface smooth to shallowly cracked or minutely fissured, lenticellate, grey or grey-fawn, inner bark fibrous, pinkish-brown, wood with slight, clear, slimy sap. Indumentum with stellate hairs and/or scales. Leaves arranged spirally, simple, entire to deeply lobed, palmately veined, stipulate. Flowers axillary, solitary or in a raceme or panicle, 5-merous; epicalyx with 3-many free or almost free segments; calyx 5-lobed or 5-parted; petals free, often large; staminal column bearing anthers throughout or in the upper half; ovary superior, 5- or 10-locular with 3-many ovules per cell, style 1, apically divided into 5 branches. Fruit a dehiscent capsule with a persistent calyx and epicalyx. Seed globose to kidney-shaped. Seedling with epigeal germination; cotyledons emergent; hypocotyl elongated; all leaves arranged spirally.

Root nodules have been observed in H. tiliaceus in the Solomon Islands, where it is explicitly used for soil restoration during fallow, but atmospheric nitrogen fixation has not been confirmed. Early growth of H. tiliaceus is rapid and in 2-3 years the tree is large enough to provide shade. In Java it attained a diameter of 42 cm in 15 years, with sapwood being 3-5 cm in width for H. tiliaceus subsp. tiliaceus and 6-7 cm for subsp. similis (Blume) Borss. Waalk. On moderately fertile to fertile soils H. tiliaceus attained a mean diameter of 24-31 cm and a mean height of 20-28 m in 11 years. H. tiliaceus develops according to Scarrone's architectural tree model, characterized by an orthotropic rhythmically active terminal meristem which produces an indeterminate trunk bearing tiers of branches, each branch-complex orthotropic and sympodially branched as a result of terminal flowering. In Java H. tiliaceus flowers more or less throughout the year, but on other Indonesian islands flowering is restricted to 1-3 months/year. Flowers are pollinated by insects and birds. Seeds of H. tiliaceus can float in seawater for several months and are commonly found along the shore.

H. tiliaceus is very polymorphic and has been divided into 5 subspecies. The name H. papuodendron Kosterm. ("bulolo ash"") occasionally appears in literature concerning Papua New Guinea timbers. The correct name is probably Papuodendron lepidotum C.T. White. Although Papuodendron is hardly distinct from Hibiscus, it is placed by some in the Malvaceae and by others in the Bombacaceae.

Root nodules have been observed in H. tiliaceus in the Solomon Islands, where it is explicitly used for soil restoration during fallow, but atmospheric nitrogen fixation has not been confirmed. Early growth of H. tiliaceus is rapid and in 2-3 years the tree is large enough to provide shade. In Java it attained a diameter of 42 cm in 15 years, with sapwood being 3-5 cm in width for H. tiliaceus subsp. tiliaceus and 6-7 cm for subsp. similis (Blume) Borss. Waalk. On moderately fertile to fertile soils H. tiliaceus attained a mean diameter of 24-31 cm and a mean height of 20-28 m in 11 years. H. tiliaceus develops according to Scarrone's architectural tree model, characterized by an orthotropic rhythmically active terminal meristem which produces an indeterminate trunk bearing tiers of branches, each branch-complex orthotropic and sympodially branched as a result of terminal flowering. In Java H. tiliaceus flowers more or less throughout the year, but on other Indonesian islands flowering is restricted to 1-3 months/year. Flowers are pollinated by insects and birds. Seeds of H. tiliaceus can float in seawater for several months and are commonly found along the shore.

H. tiliaceus is very polymorphic and has been divided into 5 subspecies. The name H. papuodendron Kosterm. ("bulolo ash"") occasionally appears in literature concerning Papua New Guinea timbers. The correct name is probably Papuodendron lepidotum C.T. White. Although Papuodendron is hardly distinct from Hibiscus, it is placed by some in the Malvaceae and by others in the Bombacaceae.

Image

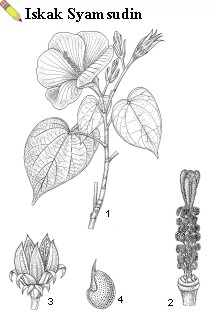

| Hibiscus tiliaceus L. – 1, flowering twig; 2, stamens and styles; 3, fruit; 4, seed. |

Ecology

Timber-yielding Hibiscus species are usually found in secondary lowland forest, forest edges and waste sites, sometimes also in primary forest, up to 1500 m altitude, rarely in montane forest up to 2400 m. They often occur in moist locations and along rivers or even in swamps. H. tiliaceus is a well-known and common element of the Barringtonia formation along sandy shores and tidal creeks. It sometimes occurs in higher sites in mangrove vegetation or further inland along rivers and lakes. H. tiliaceus subsp. similis, however, is never found along or near the shore.

Silviculture and Management

Hibiscus is easily raised from seed or by cuttings and air layering, although for H. macrophyllus propagation by cuttings has been reported as difficult. H. tiliaceus subsp. similis apparently rarely sets seed, and is propagated by cuttings. It may be a hybrid. The only seed count available is for H. macrophyllus: about 146 000 dry seeds/kg. Seeds cannot be stored, although those of H. tiliaceus may still germinate after floating at sea for months. Seed of H. tiliaceus shows about 30% germination in 23-48 days. Cuttings are generally very successful and a trial plantation using cuttings planted at 3 m x 1 m was established in Java. There, the canopy had closed after only 2 years and the first thinning was done at the age of 5. As it has a tendency to develop many low and thick branches, gradual opening of the canopy is essential. It also proved susceptible to damage by wind and did not suppress "alang-alang"" (Imperata cylindrica (L.) Raeuschel) satisfactorily. In Peninsular Malaysia H. tiliaceus is recommended for planting on poor soils for firewood production. In general, it can be planted on a wide range of soils and is highly salt tolerant. H. tiliaceus coppices readily and, when cut back, produces many long, vigorous shoots with a high fibre production. In the Solomon Islands, however, coppicing reduced vigour. In some areas H. tiliaceus can form dense thickets over large areas, where trees regenerate by layering and new erect shoots from the branches of old trees. This habit of regeneration can be common especially after cyclones.

Genetic Resources and Breeding

H. campylosiphon is rare and its use may reduce its genetic resource base. Other Malesian species, apart from H. tiliaceus, have a restricted distribution, but some are planted outside their natural area of distribution which thus contributes to their genetic conservation.

Prospects

Due to its relative abundance along the shore, H. tiliaceus will probably continue to be used on a local scale for a wide array of purposes, but the use and trade of the timber of Hibiscus are unlikely to increase in the near future.

Literature

[70]Backer, C.A. & Bakhuizen van den Brink Jr., R.C., 1963-1968. Flora of Java. 3 volumes. Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen.

[101]Beekman, H., 1920. 78 Preanger houtsoorten. Beschrijving, afbeelding en determinatietabel [78 Priangan wood species. Description, pictures and identification key]. Mededeelingen No 5. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[160]Bureau of Yards and Docks, 1944. Native woods for construction purposes in the Western Pacific Region. Department of the Navy, Washington, D.C., v + 382 pp.

[161]Burger, D., 1972. Seedlings of some tropical trees and shrubs mainly of South East Asia. Pudoc, Wageningen. 399 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[192]Chowdhury, K.A. & Ghosh, S.S., 1958. Indian woods: their identification, properties and uses. Vol. 1: Dilleniaceae to Elaeocarpaceae. Manager of Publications, Delhi. 304 pp.

[209]Corner, E.J.H., 1988. Wayside trees of Malaya. 3rd edition. 2 volumes. The Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur. 774 pp.

[235]de Guzman, E.D., Umali, R.M. & Sotalbo, E.D., 1986. Guide to the Philippine flora and fauna. Vol. 3: Dipterocarps, non-dipterocarps. Natural Resources Management Centre, Ministry of Natural Resources, Quezon City & University of the Philippines, Los Baños. xx + 414 pp.

[260]den Berger, L.G., 1926. Houtsoorten der cultuurgebieden van Java en Sumatra's oostkust [Tree species of the cultivated areas of Java and the east coast of Sumatra]. Mededeelingen No 13. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[300]Eddowes, P.J., 1977. Commercial timbers of Papua New Guinea, their properties and uses. Forest Products Research Centre, Department of Primary Industry, Port Moresby. xiv + 195 pp.

[304]Eddowes, P.J., 1995-1997. The forests and timbers of Papua New Guinea. (unpublished data).

[346]Foreman, D.B., 1971. A check list of the vascular plants of Bougainville with descriptions of some common forest trees. Botany Bulletin No 5. Division of Botany, Department of Forests, Lae. 194 pp.

[402]Hallé, F., Oldeman, R.A.A. & Tomlinson, P.B., 1978. Tropical trees and forests - an architectural analysis. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. 441 pp.

[405]Hardjowasono, M.S., 1942. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of various fruits and seeds]. Korte Mededelingen No 20. Bosbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 172 pp.

[431]Henderson, C.P. & Hancock, I.R., 1989. A guide to the useful plants of the Solomon Islands. Research Department, Ministry of Agriculture and Lands, Honiara. xiii + 481 pp.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[443]Holdsworth, D.K., 1977. Medicinal plants of Papua New Guinea. Technical Paper No 175. South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 123 pp.

[464]Ilic, J., 1990. The CSIRO macro key for hardwood identification. CSIRO, Highett. 125 pp.

[488]Japing, H.W. & Oey Djoen Seng, 1936. Cultuurproeven met wildhoutsoorten in Gadoengan - met overzicht van de literatuur betreffende deze soorten [Trial plantations of non teak wood species in Gadungan (East Java) - with survey of literature about these species]. Korte Mededeelingen No 55, part I to VI. Boschbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 270 pp.

[495]Johns, R.J., 1976. Common forest trees of Papua New Guinea. Part 7. Angiospermae: Ebenales, Malvales. Forest College, Bulolo. pp. 286-336.

[532]Kartawinata, K. & Sastrapradja, S. (Editors), 1979. Kayu Indonesia [Indonesian woods]. LBN 14. SDE 55. Lembaga Biologi Nasional - LIPI, Bogor. 116 pp.

[568]Kingston, R.S.T. & Risdon, C.J.E., 1961. Shrinkage and density of Australian and other South-West Pacific woods. Technological Paper No 13. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 65 pp.

[632]Kraemer, J.H., 1951. Trees of the western Pacific region. Tri-State Offset Company, Cincinnatti. 436 pp.

[633]Kramer, F., 1925. Kultuurproeven met industrie-, konstruktie- en luxe-houtsoorten [Investigations regarding the cultivation of different Javanese trees]. Mededeelingen No 12. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 99 pp.

[671]Leach, A.J., Leach, D.N. & Leach, G.J., 1988. Antibacterial activity of some medicinal plants of Papua New Guinea. Science in New Guinea 14(1): 1-7.

[818]National Academy of Sciences, 1983. Firewood crops. Shrub and tree species for energy production. Volume 2. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C. 92 pp.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[861]Oey Djoen Seng, 1951. De soortelijke gewichten van Indonesische houtsoorten en hun betekenis voor de praktijk [Specific gravity of Indonesian woods and its significance for practical use]. Rapport No 46. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 183 pp.

[889]Phengklai, C. & Khamsai, S., 1985. Some non-timber species of Thailand. Thai Forest Bulletin (Botany) 15: 108-148.

[893]Phuphathanaphong, L., Siriruksa, P. & Nuvongsri, G., 1989. The genus Hibiscus in Thailand. Thai Forest Bulletin (Botany) 18: 43-79.

[934]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[955]Rocafort, J.E., Floresca, A.R. & Siopongco, J.O., 1971. Fourth progress report on the specific gravity of Philippine woods. Philippine Architecture, Engineering & Construction Report 18(5): 17-27.

[974]Salvosa, F.M., 1963. Lexicon of Philippine trees. Bulletin No 1. Forest Products Research Institute, College, Laguna. 136 pp.

[1023]Sjape'ie, I., 1954. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of various fruits and seeds]. Korte mededeling 20A. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 10 pp.

[1038]Smitinand, T., 1980. Thai plant names. Royal Forest Department, Bangkok. 379 pp.

[1048]Soepadmo, E., Wong, K.M. & Saw, L.G. (Editors), 1995-. Tree flora of Sabah and Sarawak. Sabah Forestry Department, Forest Research Institute Malaysia and Sarawak Forestry Department, Kepong.

[1118]van Borssum Waalkes, J., 1966. Malesian Malvaceae revised. Blumea 14: 1-251.

[1169]Vidal, J., 1962. Noms vernaculaires de plantes en usage au Laos [Vernacular names of plants used in Laos]. Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, Paris. 197 pp.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1232]Wisse, J.H., 1965. Volumegewichten van een aantal houtmonsters uit West Nieuw Guinea [Specific gravity of some wood samples from West New Guinea]. Afdeling Bosexploitatie en Boshuishoudkunde, Landbouwhogeschool, Wageningen. 23 pp.

[1242]Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 30. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 259 pp.

[101]Beekman, H., 1920. 78 Preanger houtsoorten. Beschrijving, afbeelding en determinatietabel [78 Priangan wood species. Description, pictures and identification key]. Mededeelingen No 5. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[160]Bureau of Yards and Docks, 1944. Native woods for construction purposes in the Western Pacific Region. Department of the Navy, Washington, D.C., v + 382 pp.

[161]Burger, D., 1972. Seedlings of some tropical trees and shrubs mainly of South East Asia. Pudoc, Wageningen. 399 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[192]Chowdhury, K.A. & Ghosh, S.S., 1958. Indian woods: their identification, properties and uses. Vol. 1: Dilleniaceae to Elaeocarpaceae. Manager of Publications, Delhi. 304 pp.

[209]Corner, E.J.H., 1988. Wayside trees of Malaya. 3rd edition. 2 volumes. The Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur. 774 pp.

[235]de Guzman, E.D., Umali, R.M. & Sotalbo, E.D., 1986. Guide to the Philippine flora and fauna. Vol. 3: Dipterocarps, non-dipterocarps. Natural Resources Management Centre, Ministry of Natural Resources, Quezon City & University of the Philippines, Los Baños. xx + 414 pp.

[260]den Berger, L.G., 1926. Houtsoorten der cultuurgebieden van Java en Sumatra's oostkust [Tree species of the cultivated areas of Java and the east coast of Sumatra]. Mededeelingen No 13. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[300]Eddowes, P.J., 1977. Commercial timbers of Papua New Guinea, their properties and uses. Forest Products Research Centre, Department of Primary Industry, Port Moresby. xiv + 195 pp.

[304]Eddowes, P.J., 1995-1997. The forests and timbers of Papua New Guinea. (unpublished data).

[346]Foreman, D.B., 1971. A check list of the vascular plants of Bougainville with descriptions of some common forest trees. Botany Bulletin No 5. Division of Botany, Department of Forests, Lae. 194 pp.

[402]Hallé, F., Oldeman, R.A.A. & Tomlinson, P.B., 1978. Tropical trees and forests - an architectural analysis. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. 441 pp.

[405]Hardjowasono, M.S., 1942. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of various fruits and seeds]. Korte Mededelingen No 20. Bosbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 172 pp.

[431]Henderson, C.P. & Hancock, I.R., 1989. A guide to the useful plants of the Solomon Islands. Research Department, Ministry of Agriculture and Lands, Honiara. xiii + 481 pp.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[443]Holdsworth, D.K., 1977. Medicinal plants of Papua New Guinea. Technical Paper No 175. South Pacific Commission, Noumea, New Caledonia. 123 pp.

[464]Ilic, J., 1990. The CSIRO macro key for hardwood identification. CSIRO, Highett. 125 pp.

[488]Japing, H.W. & Oey Djoen Seng, 1936. Cultuurproeven met wildhoutsoorten in Gadoengan - met overzicht van de literatuur betreffende deze soorten [Trial plantations of non teak wood species in Gadungan (East Java) - with survey of literature about these species]. Korte Mededeelingen No 55, part I to VI. Boschbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 270 pp.

[495]Johns, R.J., 1976. Common forest trees of Papua New Guinea. Part 7. Angiospermae: Ebenales, Malvales. Forest College, Bulolo. pp. 286-336.

[532]Kartawinata, K. & Sastrapradja, S. (Editors), 1979. Kayu Indonesia [Indonesian woods]. LBN 14. SDE 55. Lembaga Biologi Nasional - LIPI, Bogor. 116 pp.

[568]Kingston, R.S.T. & Risdon, C.J.E., 1961. Shrinkage and density of Australian and other South-West Pacific woods. Technological Paper No 13. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 65 pp.

[632]Kraemer, J.H., 1951. Trees of the western Pacific region. Tri-State Offset Company, Cincinnatti. 436 pp.

[633]Kramer, F., 1925. Kultuurproeven met industrie-, konstruktie- en luxe-houtsoorten [Investigations regarding the cultivation of different Javanese trees]. Mededeelingen No 12. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 99 pp.

[671]Leach, A.J., Leach, D.N. & Leach, G.J., 1988. Antibacterial activity of some medicinal plants of Papua New Guinea. Science in New Guinea 14(1): 1-7.

[818]National Academy of Sciences, 1983. Firewood crops. Shrub and tree species for energy production. Volume 2. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C. 92 pp.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[861]Oey Djoen Seng, 1951. De soortelijke gewichten van Indonesische houtsoorten en hun betekenis voor de praktijk [Specific gravity of Indonesian woods and its significance for practical use]. Rapport No 46. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 183 pp.

[889]Phengklai, C. & Khamsai, S., 1985. Some non-timber species of Thailand. Thai Forest Bulletin (Botany) 15: 108-148.

[893]Phuphathanaphong, L., Siriruksa, P. & Nuvongsri, G., 1989. The genus Hibiscus in Thailand. Thai Forest Bulletin (Botany) 18: 43-79.

[934]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[955]Rocafort, J.E., Floresca, A.R. & Siopongco, J.O., 1971. Fourth progress report on the specific gravity of Philippine woods. Philippine Architecture, Engineering & Construction Report 18(5): 17-27.

[974]Salvosa, F.M., 1963. Lexicon of Philippine trees. Bulletin No 1. Forest Products Research Institute, College, Laguna. 136 pp.

[1023]Sjape'ie, I., 1954. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of various fruits and seeds]. Korte mededeling 20A. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 10 pp.

[1038]Smitinand, T., 1980. Thai plant names. Royal Forest Department, Bangkok. 379 pp.

[1048]Soepadmo, E., Wong, K.M. & Saw, L.G. (Editors), 1995-. Tree flora of Sabah and Sarawak. Sabah Forestry Department, Forest Research Institute Malaysia and Sarawak Forestry Department, Kepong.

[1118]van Borssum Waalkes, J., 1966. Malesian Malvaceae revised. Blumea 14: 1-251.

[1169]Vidal, J., 1962. Noms vernaculaires de plantes en usage au Laos [Vernacular names of plants used in Laos]. Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, Paris. 197 pp.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1232]Wisse, J.H., 1965. Volumegewichten van een aantal houtmonsters uit West Nieuw Guinea [Specific gravity of some wood samples from West New Guinea]. Afdeling Bosexploitatie en Boshuishoudkunde, Landbouwhogeschool, Wageningen. 23 pp.

[1242]Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 30. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 259 pp.

Author(s)

S.I. Wiselius

Hibiscus borneensis

Hibiscus campylosiphon

Hibiscus d'albertisii

Hibiscus decaspermus

Hibiscus floccosus

Hibiscus macrophyllus

Hibiscus pleijtei

Hibiscus schizopetalus

Hibiscus tiliaceus

Hibiscus campylosiphon

Hibiscus d'albertisii

Hibiscus decaspermus

Hibiscus floccosus

Hibiscus macrophyllus

Hibiscus pleijtei

Hibiscus schizopetalus

Hibiscus tiliaceus

Correct Citation of this Article

Wiselius, S.I., 1998. Hibiscus L.. In: Sosef, M.S.M., Hong, L.T. and Prawirohatmodjo, S. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

Selection of Species

The following species in this genus are important in this commodity group and are treated separatedly in this database:

Hibiscus borneensis

Hibiscus campylosiphon

Hibiscus d'albertisii

Hibiscus decaspermus

Hibiscus floccosus

Hibiscus macrophyllus

Hibiscus pleijtei

Hibiscus schizopetalus

Hibiscus tiliaceus

Hibiscus borneensis

Hibiscus campylosiphon

Hibiscus d'albertisii

Hibiscus decaspermus

Hibiscus floccosus

Hibiscus macrophyllus

Hibiscus pleijtei

Hibiscus schizopetalus

Hibiscus tiliaceus

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.