Record Number

5783

PROSEA Handbook Number

5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers

Taxon

Mallotus Lour.

Protologue

Fl. Cochinch.: 635 (1790).

Family

EUPHORBIACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

x = 11; M. albus Müll. Arg.: n = 33, M. philippensis, M. repandus (Willd.) Müll. Arg., M. resinosus (Blanco) Merr.: n = 11

Vernacular Names

Indonesia: balik angin (general), tutup, walik angin (Javanese). Malaysia: balek angin (general), enserai (Sarawak), mallotus (Sabah). Philippines: banato (general), hinlaumo (Cebu and Panay Bisaya). Vietnam: ba b[es]t, b[uj]c b[uj]c, b[uf]ng b[uj]c.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Mallotus comprises about 150 species. Only 2 of these occur in Africa and Madagascar, the rest are found from India and Sri Lanka to Indo-China, China, Taiwan, Japan, Thailand, throughout the Malesian region, northern Australia and the Pacific (east to Fiji). Some 50 species are found within Malesia.

Uses

The wood of Mallotus is used for temporary construction (poles), non-striking tool handles, matches, disposable chopsticks, wooden shoes, packing cases, pegs and possibly for turnery articles. Due to its generally small size, the wood is probably more often used for particle board and fibreboard production, and for the production of pulp and paper. It yields a good firewood.

Some species are planted as live fences or as ornamentals and shade trees. In India M. philippensis is considered to be a valuable nurse tree for more important forest tree species, e.g. sal (Shorea robusta Gaertn. f.). The fibrous bark is used to make rope and artificial fur. The fruits and bark have been reported to be used medicinally to treat stomach ulcers and tapeworm. Logs of M. paniculatus proved suitable for shiitake mushroom cultivation. The granules covering the fruit of M. philippensis provide a bright orange dye; a red dye has been extracted from the roots. Seeds of this species, and probably also of others, yield an oil used as a substitute for tung oil (obtained from Aleurites spp.), in the production of paint and varnish. The oil is also used as a fixative in cosmetic preparations and for colouring foodstuffs and beverages. All parts of this tree can be applied externally to treat parasitic infections of the skin. Several other species are reported to contain tannins. Leaves of several species are used to make tea. Flowers of M. floribundus are fragrant and used to flavour food and in decorations. Foliage of M. philippensis is used for fodder.

Some species are planted as live fences or as ornamentals and shade trees. In India M. philippensis is considered to be a valuable nurse tree for more important forest tree species, e.g. sal (Shorea robusta Gaertn. f.). The fibrous bark is used to make rope and artificial fur. The fruits and bark have been reported to be used medicinally to treat stomach ulcers and tapeworm. Logs of M. paniculatus proved suitable for shiitake mushroom cultivation. The granules covering the fruit of M. philippensis provide a bright orange dye; a red dye has been extracted from the roots. Seeds of this species, and probably also of others, yield an oil used as a substitute for tung oil (obtained from Aleurites spp.), in the production of paint and varnish. The oil is also used as a fixative in cosmetic preparations and for colouring foodstuffs and beverages. All parts of this tree can be applied externally to treat parasitic infections of the skin. Several other species are reported to contain tannins. Leaves of several species are used to make tea. Flowers of M. floribundus are fragrant and used to flavour food and in decorations. Foliage of M. philippensis is used for fodder.

Production and International Trade

The wood of Mallotus is used on a local scale only, mainly because the logs are small.

Properties

Mallotus yields a lightweight to medium-weight hardwood with a density of 370-830 kg/m3 at 15% moisture content. Heartwood straw-coloured or pale brown, not clearly differentiated from the sapwood; grain straight; texture moderately fine to slightly coarse, even. Growth rings indistinct or visible (e.g. M. muticus and M. philippensis) due to darker bands with little or no parenchyma; vessels medium-sized, solitary and in radial multiples of 2-10, occasionally in clusters of up to 4, often with a greater number of solitary vessels in comparison to other Euphorbiaceae spp., occasional tyloses present; parenchyma moderately abundant, apotracheal in narrow bands to diffuse to diffuse-in-aggregates; rays extremely fine or very fine, inconspicuous on radial surface; ripple marks absent; pith flecks sometimes present.

Shrinkage upon air drying is moderate (M. muticus) to very high (M. floribundus) with moderate risk of splitting, insect attack and staining, and with a slight risk of cupping, bowing and end-checking. It takes about 2 months and 3 months respectively to air dry boards of M. muticus 13 mm and 38 mm thick. The wood is soft to moderately hard and fairly weak to moderately strong. It is generally easy to work, but is reported to be difficult to resaw and cross-cut because it is fibrous; planing is easy to moderately easy giving a moderately smooth surface. The harder species (e.g. M. philippensis) are said to turn well. Durability is probably linked to the density of individual species and is classified as non-durable for the lighter species and slightly durable for the heavier ones. The wood is extremely easy to treat with preservatives. It is not resistant to termites and marine borers. The sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus.

See also the tables on microscopic wood anatomy and wood properties.

Shrinkage upon air drying is moderate (M. muticus) to very high (M. floribundus) with moderate risk of splitting, insect attack and staining, and with a slight risk of cupping, bowing and end-checking. It takes about 2 months and 3 months respectively to air dry boards of M. muticus 13 mm and 38 mm thick. The wood is soft to moderately hard and fairly weak to moderately strong. It is generally easy to work, but is reported to be difficult to resaw and cross-cut because it is fibrous; planing is easy to moderately easy giving a moderately smooth surface. The harder species (e.g. M. philippensis) are said to turn well. Durability is probably linked to the density of individual species and is classified as non-durable for the lighter species and slightly durable for the heavier ones. The wood is extremely easy to treat with preservatives. It is not resistant to termites and marine borers. The sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus.

See also the tables on microscopic wood anatomy and wood properties.

Botany

Evergreen, dioecious or rarely monoecious shrubs or small to medium-sized trees up to 25(-35) m tall; bole straight to sinuous, up to 50(-80) cm in diameter, occasionally with short or steep buttresses; bark thin, surface smooth, white or pale grey, inner bark fibrous, brown to reddish or dark red. Indumentum often of stellate hairs. Leaves arranged spirally or opposite, simple, entire, sometimes peltate, often whitish and with glandular granules below, venation pinnate or palmate; stipules small. Flowers in a terminal or axillary raceme or spike, unisexual; petals absent. Male flower with 3-4-lobed calyx; stamens numerous; disk absent, lobed or annular. Female flower with 3-5-lobed calyx; disk absent; ovary superior, (2-)3(-4)-locular with 1 ovule in each cell, styles elongate, simple or plumose. Fruit a lobed, thinly woody, smooth to echinate capsule, splitting into 2-valved parts and a persistant central column. Seed smooth, shiny black, sometimes with a small aril. Seedling with epigeal germination; cotyledons emergent, leafy; hypocotyl elongated; first few leaves arranged spirally, decussate higher up in species with opposite leaves.

In the Philippines a mean annual diameter increment of 1.4 cm has been recorded for M. philippensis trees in the diameter class 10-20 cm, whereas for M. mollissimus it is 1.7-1.9 cm and 3.6 cm for trees in the diameter classes 0-20 cm and 20-30 cm, respectively. In the Philippines M. philippensis flowers from March to April. M. philippensis has extrafloral nectaries attracting ants. The seeds of many Mallotus species are dispersed by birds.

Mallotus is closely related to Macaranga, the latter differing by its 3-4-celled anthers and more conspicuously by its lateral inflorescences and absence of stellate hairs.

In the Philippines a mean annual diameter increment of 1.4 cm has been recorded for M. philippensis trees in the diameter class 10-20 cm, whereas for M. mollissimus it is 1.7-1.9 cm and 3.6 cm for trees in the diameter classes 0-20 cm and 20-30 cm, respectively. In the Philippines M. philippensis flowers from March to April. M. philippensis has extrafloral nectaries attracting ants. The seeds of many Mallotus species are dispersed by birds.

Mallotus is closely related to Macaranga, the latter differing by its 3-4-celled anthers and more conspicuously by its lateral inflorescences and absence of stellate hairs.

Image

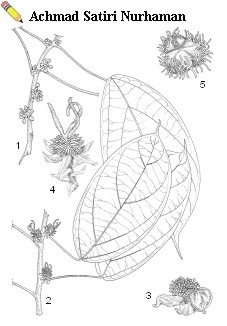

| Mallotus subpeltatus (Blume) Müll. Arg. – 1, male flowering twig; 2, female flowering twig; 3, male flower; 4, female flower; 5, fruit. |

Ecology

Most Mallotus species occur in primary evergreen rain forest, but a few are abundant in secondary forest and in more open locations including savanna woodland, up to 2000 m altitude. They occur in dipterocarp, riverine and swamp forest. A few species (e.g. M. philippensis) are pioneers characteristic of secondary vegetation and may be gregarious elements in regenerated forest. They are among the first species appearing after fields are abandoned. Individual species have been found on a wide variety of soil types including limestone soils.

Silviculture and Management

Mallotus can be propagated by seed; the only available seed count is for M. paniculatus having about 115 000 dry seeds/kg. Seeds of M. leucodermis still embedded in their aril have about 45% germination in 5-20 days, those of M. philippensis about 5% in 65-82 days. In India shade and adequate moisture are considered important for the production of seedlings. Most Mallotus species are light-demanding, but some need shade in the early phases of establishment. In India established M. philippensis is frost-hardy and resistant to drought and it coppices well and is capable of producing root suckers. M. philippensis is not resistant to fire.

Genetic Resources and Breeding

As most Mallotus species are light-demanding and exhibit pioneer characteristics, they are at little risk of genetic erosion by deforestation.

Prospects

It has been suggested to use M. philippensis to protect soil and simultaneously produce wood, possibly for pulp, wood-based panels or firewood. Since little is known about the silviculture of Mallotus species that have potential for reforestation or for plantation establishment, more research is needed on specific silvicultural aspects.

Literature

[26]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1972. The Euphorbiaceae of Siam. Kew Bulletin 26: 191-363.

[28]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1975. The Euphorbiaceae of Borneo. Kew Bulletin Additional Series VIII. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London. 245 pp.

[32]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1980. The Euphorbiaceae of New Guinea. Kew Bulletin Additional Series VIII. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London. 243 pp.

[33]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1981. An alphabetical enumeration of the Euphorbiaceae of the Philippine islands. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 56 pp.

[34]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1981. The Euphorbiaceae of Sumatra. Kew Bulletin 36: 239-374.

[36]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1983. The Euphorbiaceae of Central Malesia (Celebes, Moluccas, Lesser Sunda Is.). Kew Bulletin 37: 1-40.

[70]Backer, C.A. & Bakhuizen van den Brink Jr., R.C., 1963-1968. Flora of Java. 3 volumes. Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[162]Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Sabah Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Sabah, Sandakan. xviii + 501 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[174]Cay go rung Viet nam [Forest trees of Vietnam] (various editors), 1971-1988. Agriculture Publisher, Hanoi.

[209]Corner, E.J.H., 1988. Wayside trees of Malaya. 3rd edition. 2 volumes. The Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur. 774 pp.

[235]de Guzman, E.D., Umali, R.M. & Sotalbo, E.D., 1986. Guide to the Philippine flora and fauna. Vol. 3: Dipterocarps, non-dipterocarps. Natural Resources Management Centre, Ministry of Natural Resources, Quezon City & University of the Philippines, Los Baños. xx + 414 pp.

[238]de Vogel, E.F., 1980. Seedlings of dicotyledons. Structure, development, types. Descriptions of 150 woody Malesian taxa. Pudoc, Wageningen. 465 pp.

[260]den Berger, L.G., 1926. Houtsoorten der cultuurgebieden van Java en Sumatra's oostkust [Tree species of the cultivated areas of Java and the east coast of Sumatra]. Mededeelingen No 13. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[387]Grewal, G.S., 1979. Air-seasoning properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 41. Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 26 pp.

[404]Hans, A.S., 1973. Chromosomal conspectus of the Euphorbiaceae. Taxon 22: 591-636.

[405]Hardjowasono, M.S., 1942. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of various fruits and seeds]. Korte Mededelingen No 20. Bosbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 172 pp.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[464]Ilic, J., 1990. The CSIRO macro key for hardwood identification. CSIRO, Highett. 125 pp.

[543]Keng, H., 1990. The concise flora of Singapore. Gymnosperms and dicotyledons. Singapore University Press, Singapore. 222 pp.

[571]Kloot, N.H. & Bolza, E., 1961. Properties of timbers imported into Australia. Technological Paper No 12. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 79 pp.

[678]Lee, Y.H., Engku Abdul Rahman bin Chik & Chu, Y.P., 1979. The strength properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 34 (revised edition). Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 107 pp.

[696]Lemmens, R.H.M.J. & Wulijarni-Soetjipto, N. (Editors), 1991. Plant resources of South-East Asia No 3. Dye and tannin-producing plants. Pudoc, Wageningen. 195 pp.

[698]Levingston, R. & Zamora, R., 1983. Medicine trees of the tropics. Unasylva 35(140): 7-10.

[712]Loi, D.T., 1986. Medicinal plants and ingredients of Vietnam. 6th Edition. Science-Technic Publisher, Hanoi. 1250 pp.

[772]Meijer Drees, E., 1951. Distribution, ecology and silvicultural possibilities of the trees and shrubs from the savanna-forest region in eastern Sumbawa and Timor (Lesser Sunda Islands). Communication No 33. Forest Research Institute, Bogor. 145 pp.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[834]Nguyen Nghia Thin, 1989. Useful plants of Euphorbiaceae in flora of Vietnam. Forestry Revue, Hanoi 1989: 29-30.

[835]Nguyen Nghia Thin, 1995. Euphorbiaceae of Vietnam. Agriculture Publishing House, Hanoi. 50 pp.

[861]Oey Djoen Seng, 1951. De soortelijke gewichten van Indonesische houtsoorten en hun betekenis voor de praktijk [Specific gravity of Indonesian woods and its significance for practical use]. Rapport No 46. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 183 pp.

[883]Pham Hoang Ho, 1991-1993. An illustrated flora of Vietnam. 2 Volumes. Mekong Publisher, Montreal.

[889]Phengklai, C. & Khamsai, S., 1985. Some non-timber species of Thailand. Thai Forest Bulletin (Botany) 15: 108-148.

[937]Richards, P.W., 1952. The tropical rain forest - an ecological study. Cambridge University Press, London, New York. 450 pp.

[955]Rocafort, J.E., Floresca, A.R. & Siopongco, J.O., 1971. Fourth progress report on the specific gravity of Philippine woods. Philippine Architecture, Engineering & Construction Report 18(5): 17-27.

[974]Salvosa, F.M., 1963. Lexicon of Philippine trees. Bulletin No 1. Forest Products Research Institute, College, Laguna. 136 pp.

[1038]Smitinand, T., 1980. Thai plant names. Royal Forest Department, Bangkok. 379 pp.

[1104]Troup, R.S., 1921. Silviculture of Indian trees. 3 volumes. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

[1169]Vidal, J., 1962. Noms vernaculaires de plantes en usage au Laos [Vernacular names of plants used in Laos]. Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, Paris. 197 pp.

[1195]Webster, G.L., 1994. Synopsis of the genera and suprageneric taxa of Euphorbiaceae. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 81: 33-144.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1232]Wisse, J.H., 1965. Volumegewichten van een aantal houtmonsters uit West Nieuw Guinea [Specific gravity of some wood samples from West New Guinea]. Afdeling Bosexploitatie en Boshuishoudkunde, Landbouwhogeschool, Wageningen. 23 pp.

[1242]Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 30. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 259 pp.

[28]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1975. The Euphorbiaceae of Borneo. Kew Bulletin Additional Series VIII. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London. 245 pp.

[32]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1980. The Euphorbiaceae of New Guinea. Kew Bulletin Additional Series VIII. Her Majesty's Stationery Office, London. 243 pp.

[33]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1981. An alphabetical enumeration of the Euphorbiaceae of the Philippine islands. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 56 pp.

[34]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1981. The Euphorbiaceae of Sumatra. Kew Bulletin 36: 239-374.

[36]Airy Shaw, H.K., 1983. The Euphorbiaceae of Central Malesia (Celebes, Moluccas, Lesser Sunda Is.). Kew Bulletin 37: 1-40.

[70]Backer, C.A. & Bakhuizen van den Brink Jr., R.C., 1963-1968. Flora of Java. 3 volumes. Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[162]Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Sabah Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Sabah, Sandakan. xviii + 501 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[174]Cay go rung Viet nam [Forest trees of Vietnam] (various editors), 1971-1988. Agriculture Publisher, Hanoi.

[209]Corner, E.J.H., 1988. Wayside trees of Malaya. 3rd edition. 2 volumes. The Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur. 774 pp.

[235]de Guzman, E.D., Umali, R.M. & Sotalbo, E.D., 1986. Guide to the Philippine flora and fauna. Vol. 3: Dipterocarps, non-dipterocarps. Natural Resources Management Centre, Ministry of Natural Resources, Quezon City & University of the Philippines, Los Baños. xx + 414 pp.

[238]de Vogel, E.F., 1980. Seedlings of dicotyledons. Structure, development, types. Descriptions of 150 woody Malesian taxa. Pudoc, Wageningen. 465 pp.

[260]den Berger, L.G., 1926. Houtsoorten der cultuurgebieden van Java en Sumatra's oostkust [Tree species of the cultivated areas of Java and the east coast of Sumatra]. Mededeelingen No 13. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[387]Grewal, G.S., 1979. Air-seasoning properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 41. Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 26 pp.

[404]Hans, A.S., 1973. Chromosomal conspectus of the Euphorbiaceae. Taxon 22: 591-636.

[405]Hardjowasono, M.S., 1942. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of various fruits and seeds]. Korte Mededelingen No 20. Bosbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 172 pp.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[464]Ilic, J., 1990. The CSIRO macro key for hardwood identification. CSIRO, Highett. 125 pp.

[543]Keng, H., 1990. The concise flora of Singapore. Gymnosperms and dicotyledons. Singapore University Press, Singapore. 222 pp.

[571]Kloot, N.H. & Bolza, E., 1961. Properties of timbers imported into Australia. Technological Paper No 12. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 79 pp.

[678]Lee, Y.H., Engku Abdul Rahman bin Chik & Chu, Y.P., 1979. The strength properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 34 (revised edition). Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 107 pp.

[696]Lemmens, R.H.M.J. & Wulijarni-Soetjipto, N. (Editors), 1991. Plant resources of South-East Asia No 3. Dye and tannin-producing plants. Pudoc, Wageningen. 195 pp.

[698]Levingston, R. & Zamora, R., 1983. Medicine trees of the tropics. Unasylva 35(140): 7-10.

[712]Loi, D.T., 1986. Medicinal plants and ingredients of Vietnam. 6th Edition. Science-Technic Publisher, Hanoi. 1250 pp.

[772]Meijer Drees, E., 1951. Distribution, ecology and silvicultural possibilities of the trees and shrubs from the savanna-forest region in eastern Sumbawa and Timor (Lesser Sunda Islands). Communication No 33. Forest Research Institute, Bogor. 145 pp.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[834]Nguyen Nghia Thin, 1989. Useful plants of Euphorbiaceae in flora of Vietnam. Forestry Revue, Hanoi 1989: 29-30.

[835]Nguyen Nghia Thin, 1995. Euphorbiaceae of Vietnam. Agriculture Publishing House, Hanoi. 50 pp.

[861]Oey Djoen Seng, 1951. De soortelijke gewichten van Indonesische houtsoorten en hun betekenis voor de praktijk [Specific gravity of Indonesian woods and its significance for practical use]. Rapport No 46. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 183 pp.

[883]Pham Hoang Ho, 1991-1993. An illustrated flora of Vietnam. 2 Volumes. Mekong Publisher, Montreal.

[889]Phengklai, C. & Khamsai, S., 1985. Some non-timber species of Thailand. Thai Forest Bulletin (Botany) 15: 108-148.

[937]Richards, P.W., 1952. The tropical rain forest - an ecological study. Cambridge University Press, London, New York. 450 pp.

[955]Rocafort, J.E., Floresca, A.R. & Siopongco, J.O., 1971. Fourth progress report on the specific gravity of Philippine woods. Philippine Architecture, Engineering & Construction Report 18(5): 17-27.

[974]Salvosa, F.M., 1963. Lexicon of Philippine trees. Bulletin No 1. Forest Products Research Institute, College, Laguna. 136 pp.

[1038]Smitinand, T., 1980. Thai plant names. Royal Forest Department, Bangkok. 379 pp.

[1104]Troup, R.S., 1921. Silviculture of Indian trees. 3 volumes. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

[1169]Vidal, J., 1962. Noms vernaculaires de plantes en usage au Laos [Vernacular names of plants used in Laos]. Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, Paris. 197 pp.

[1195]Webster, G.L., 1994. Synopsis of the genera and suprageneric taxa of Euphorbiaceae. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 81: 33-144.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1232]Wisse, J.H., 1965. Volumegewichten van een aantal houtmonsters uit West Nieuw Guinea [Specific gravity of some wood samples from West New Guinea]. Afdeling Bosexploitatie en Boshuishoudkunde, Landbouwhogeschool, Wageningen. 23 pp.

[1242]Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 30. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 259 pp.

Author(s)

Nguyen Nghia Thin & Tran Van On

Mallotus blumeanus

Mallotus floribundus

Mallotus leucodermis

Mallotus macrostachyus

Mallotus mollissimus

Mallotus muticus

Mallotus oblongifolius

Mallotus paniculatus

Mallotus philippensis

Mallotus subpeltatus

Mallotus tiliifolius

Mallotus floribundus

Mallotus leucodermis

Mallotus macrostachyus

Mallotus mollissimus

Mallotus muticus

Mallotus oblongifolius

Mallotus paniculatus

Mallotus philippensis

Mallotus subpeltatus

Mallotus tiliifolius

Correct Citation of this Article

Thin, N.N. & On, T.V., 1998. Mallotus Lour.. In: Sosef, M.S.M., Hong, L.T. and Prawirohatmodjo, S. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

Selection of Species

The following species in this genus are important in this commodity group and are treated separatedly in this database:

Mallotus blumeanus

Mallotus floribundus

Mallotus leucodermis

Mallotus macrostachyus

Mallotus mollissimus

Mallotus muticus

Mallotus oblongifolius

Mallotus paniculatus

Mallotus philippensis

Mallotus subpeltatus

Mallotus tiliifolius

Mallotus blumeanus

Mallotus floribundus

Mallotus leucodermis

Mallotus macrostachyus

Mallotus mollissimus

Mallotus muticus

Mallotus oblongifolius

Mallotus paniculatus

Mallotus philippensis

Mallotus subpeltatus

Mallotus tiliifolius

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.