Record Number

580

PROSEA Handbook Number

13: Spices

Taxon

Myristica fragrans Houtt.

Protologue

Nat. hist., part 2 (plants), fascicle 3: 333 (1774).

Family

MYRISTICACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 44; the chromosomes are holokinetic, i.e. with the spindle attached along their whole length

Synonyms

Myristica officinalis L.f. (1781), Myristica moschata Thunb. (1782), Myristica aromatica Lamk (1788).

Vernacular Names

Nutmeg (En). Noix de muscade (Fr). Indonesia: pala, pala Banda. Malaysia: pala. Philippines: duguan. Singapore: pokok pala. Burma (Myanmar): mutwinda. Cambodia: pôch kak. Laos: chan th'e:d. Thailand: chan-thet (central), chan-ban (northern). Vietnam: nh[uj]c d[aaj]u kh[aas]u.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Nutmeg is only known from cultivation but it most probably originated in Indonesia from the southern Moluccan Islands, especially Ambon and Banda. Nutmeg and mace (the dried aril) spread from there and became known throughout South-East Asia. The first record in Europe, in Constantinople, dates from 540 AD. By the end of the 12th Century nutmeg and mace were generally known in Europe. The further history of nutmeg is closely related to an aggressive colonial history. In 1512, the Portuguese discovered Banda and obtained a monopoly on nutmeg. In the 17th Century they were ousted by the Dutch who took over the monopoly, and held to it rigorously, even by extirpation of trees grown elsewhere, to keep the prices high. In 1772, the French broke the monopoly, and the British ended it in 1802, during their rule of Indonesia. In those days centres of cultivation came into being in other parts of the tropics; they all disappeared again, some due to diseases. In 1843 some plants were introduced into Grenada (West Indies); this led to large-scale production on that island, which has become the second largest producer after Indonesia.

At present the main centre of cultivation is Banda and surrounding islands. Nutmeg is cultivated on a smaller scale on other Indonesian islands, notably North Sulawesi (Manado), western Sumatra, West Java and in Irian Jaya. Sri Lanka, India (Kerala) and the island of Pinang off Peninsular Malaysia also have sizable acreages. The crop has also been dispersed to many other per-humid or humid tropical regions and enters the world market also from there, albeit on a small scale.

At present the main centre of cultivation is Banda and surrounding islands. Nutmeg is cultivated on a smaller scale on other Indonesian islands, notably North Sulawesi (Manado), western Sumatra, West Java and in Irian Jaya. Sri Lanka, India (Kerala) and the island of Pinang off Peninsular Malaysia also have sizable acreages. The crop has also been dispersed to many other per-humid or humid tropical regions and enters the world market also from there, albeit on a small scale.

Uses

The nutmeg products, dry shelled seed (nutmeg) and dried aril (mace) are sold as spices whole or ground. In most countries grated nutmeg is used in small quantities to flavour confectionery but in western Europe it is also used in meat dishes and soups. Mace is preferably used in savoury dishes, pickles and ketchups. Essential oils (mostly nutmeg oil from the seed and mace oil from the aril, but also from the bark, leaf and flower) and extracts (e.g. oleoresins) are often used in the canning industry, in soft drinks and in cosmetics. Nutmeg quality 'BWP' (broken, wormy and punky) and mouldy nutmegs are often used for distilling essential oil. In the United States the regulatory status 'generally recognized as safe' has been accorded to nutmeg (GRAS 2792), nutmeg oil (GRAS 2793), mace (GRAS 2652), mace oil (GRAS 2653) and mace oleoresin (GRAS 2654). Nutmeg oil is extensively used as a flavour component in major food products; the maximum permitted level in food is about 0.08%. The essential oil has insecticidal, fungicidal and bactericidal activity. Nutmeg can be used as a narcotic with hallucinogenic effects but it is dangerous; the consumption of two ground nutmegs (about 8 g) is said to cause death, due to its myristicin content. On Zanzibar nutmegs are chewed as an alternative to smoking marihuana. Medicinally, nutmeg is said to have stimulant, carminative, astringent and aphrodisiac properties. Young husks (pericarps) are made into confectionery (jellies, marmalades, sweets and preserves, very popular in West Java and Malaysia). Old husks can be used as substrate to grow the popular edible mushroom 'kulat pala' (Volvariella volvacea (Bull. ex Fr.) Sing), which possesses a light nutmeg flavour. Nutmeg butter, a fixed oil obtained by pressing the seeds, is used in ointments and perfumery.

Production and International Trade

Annual world production of nutmeg is about 17 000 t and of mace 3000 t. Approximately 60% of the nutmeg and mace entering the world market is produced in Indonesia and 30% in Grenada. Small quantities from Sri Lanka are also traded internationally. In 1994 Indonesia produced 14 000 t nutmeg and mace from 67 000 ha, and exported 7900 t nutmeg and 1400 t mace.

Major importers are the United States, Germany, the Netherlands, Great Britain and Japan. Prices are approximately: nutmeg US$ 7/kg, mace US$ 13.5/kg.

Since July 1987 the Grenada Cooperative Nutmeg Association and the Indonesian Nutmeg Association have reached an agreement on yearly sales on the international market. Indonesia is allowed to sell 6000 t of nutmeg and 1250 t of mace, and Grenada 2000 t of nutmeg and 350 t of mace.

Major importers are the United States, Germany, the Netherlands, Great Britain and Japan. Prices are approximately: nutmeg US$ 7/kg, mace US$ 13.5/kg.

Since July 1987 the Grenada Cooperative Nutmeg Association and the Indonesian Nutmeg Association have reached an agreement on yearly sales on the international market. Indonesia is allowed to sell 6000 t of nutmeg and 1250 t of mace, and Grenada 2000 t of nutmeg and 350 t of mace.

Properties

Per 100 g edible portion nutmeg contains approximately: water 10 g, protein 7 g, fat (nutmeg butter) 33 g, essential oil 5 g, carbohydrates 30 g, fibre 11 g, ash 2 g (Ca 0.1 g, P 0.2 g, Fe 4.5 mg). Nutmeg butter is a highly aromatic, orange-red to red-brown fat with the consistency of butter at ambient temperature; it can be obtained by pressing the nutmeg under heat; it contains mainly trimyristin and a high proportion of essential oil which is difficult to separate. Nutmeg essential oil is pale yellow to almost water-white with a fresh, warm spicy, aromatic odour; its major components are: monoterpene hydrocarbons (61-88%, e.g. 'ALFA'-pinene, 'BETA'-pinene, sabinene), oxygenated monoterpenes (5-15%) and aromatic ethers (2-18%, e.g. myristicin, elemicin, safrole). Differences in oil composition influence the nutmeg flavour considerably: East Indian oils have a stronger nutmeg flavour because of a greater proportion of myristicin and safrole than the West Indian oils, which are richer in elemicin. Sri Lankan oil resembles West Indian oil. Commercial nutmeg extract from Papua New Guinea was found to be rich in safrole, but this may be due to adulteration with extract or oil from other Myristica, possibly Myristica argentea.

Per 100 g edible portion mace contains approximately: water 16 g, fat 22 g, essential oil 10 g, carbohydrates 48 g, P 0.1 g, Fe 13 mg. The red pigment in mace is lycopene and is identical with the red colourant in tomato. Mace essential oil is colourless to pale yellow, much resembling nutmeg oil; it is produced in very small quantities.

Nutmeg and mace oleoresins can be prepared by extracting with organic solvents and they contain essential oil, fixed oil and other extractives soluble in the chosen solvent. Hydrocarbon solvents result in a higher fixed-oil content than polar solvents such as alcohol and acetone. Nutmeg and mace oleoresins are considered to possess a more true odour and flavour than the corresponding essential oils and are preferred in food industries. Nutmeg oleoresin is a pale to golden-brown viscous liquid, clear and oily or opaque and waxy, becoming clear on warming to 50°C, graded on volatile-oil content (ml/100 g) as 25-30, 55-60, 80 and 80-90. Mace oleoresin is an amber to reddish-amber clear liquid and graded on volatile-oil content as 8-24, 40-45, 50 and 50-56.

The hallucinogenic properties of nutmeg have been ascribed to the aromatic ethers safrole, myristicin and elemicin. It is assumed that they are ammoniated and metabolized in the body to the potent ecstasy-like amphetamines MDA (3,4-methylenedioxy amphetamine), MMDA (3-methoxy-4,5-methylenedioxy amphetamine) and TMA (trimethoxy amphetamine) respectively.

Monographs on the physiological properties of nutmeg oil and mace oil have been published by the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM).

Per 100 g edible portion mace contains approximately: water 16 g, fat 22 g, essential oil 10 g, carbohydrates 48 g, P 0.1 g, Fe 13 mg. The red pigment in mace is lycopene and is identical with the red colourant in tomato. Mace essential oil is colourless to pale yellow, much resembling nutmeg oil; it is produced in very small quantities.

Nutmeg and mace oleoresins can be prepared by extracting with organic solvents and they contain essential oil, fixed oil and other extractives soluble in the chosen solvent. Hydrocarbon solvents result in a higher fixed-oil content than polar solvents such as alcohol and acetone. Nutmeg and mace oleoresins are considered to possess a more true odour and flavour than the corresponding essential oils and are preferred in food industries. Nutmeg oleoresin is a pale to golden-brown viscous liquid, clear and oily or opaque and waxy, becoming clear on warming to 50°C, graded on volatile-oil content (ml/100 g) as 25-30, 55-60, 80 and 80-90. Mace oleoresin is an amber to reddish-amber clear liquid and graded on volatile-oil content as 8-24, 40-45, 50 and 50-56.

The hallucinogenic properties of nutmeg have been ascribed to the aromatic ethers safrole, myristicin and elemicin. It is assumed that they are ammoniated and metabolized in the body to the potent ecstasy-like amphetamines MDA (3,4-methylenedioxy amphetamine), MMDA (3-methoxy-4,5-methylenedioxy amphetamine) and TMA (trimethoxy amphetamine) respectively.

Monographs on the physiological properties of nutmeg oil and mace oil have been published by the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM).

Adulterations and Substitutes

Seed of several other Myristica species can be found as adulteration or substitute of the true nutmeg, e.g. of Myristica argentea Warb. (the Papua nutmeg, wild and cultivated in Irian Jaya and Papua New Guinea); Myristica castaneifolia A. Gray (from the Fiji Islands); Myristica cinnamomea King (from Malaysia, Singapore, Sumatra, Borneo and the Philippines); Myristica crassa King (from Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Sumatra); Myristica dactyloides Gaertner (from Sri Lanka); Myristica elliptica Wallich ex Hook.f. & Thomson (the swamp nutmeg, widespread in west Malesia and Thailand); Myristica fatua Houtt. (from Kalimantan, Sulawesi, the Moluccas and the Philippines); Myristica malabarica Lamk (the Bombay nutmeg from the west coast of peninsular India); Myristica muelleri Warb. (Australia, north-eastern Queensland); Myristica succedanea Blume (the Halmahera nutmeg, wild and cultivated in the northern Moluccas); and Myristica womersleyi J. Sinclair (from New Guinea). In Africa, seed of the calabash or African nutmeg Monodora myristica Dunal (Annonaceae) and on Madagascar the clove-nutmeg Ravensara aromatica Gmelin (Sonneratiaceae) are used as substitutes of nutmeg. In South America the Brazil nutmeg Cryptocarya moschata Nees & Martius (Lauraceae) and in the United States the Californian nutmeg Torreya californica Torr. (Taxaceae) are similarly used.

Description

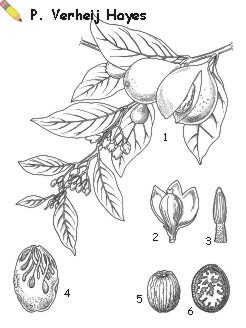

A dioecious evergreen tree, 5-13(-20) m tall, cone-shaped if free-growing, exuding a sticky red sap when wounded. Twigs slender, 1-2 mm in diameter towards the top. Leaves alternate, simple, exstipulate, chartaceous; petiole about 1 cm long; blade elliptical to lanceolate, 5-15 cm x 3-7 cm, base acute, margin entire, apex acuminate, aromatic when bruised. Inflorescences axillary, in umbellate cymes, male ones usually many-flowered, female ones 1-3-flowered; flowers fragrant, glabrescent with sparse, very minute tomentum, pale yellow, with a 3-lobed perianth; male flowers with a slender pedicel less than 1 mm thick, a usually slightly narrowed perianth at the base, and 8-12 stamens adnate to a column; female flowers with a superior, sessile, 1-celled ovary with a single basal ovule, which is normally anatropous to hemi-anatropous. Fruit peach-shaped, berry or drupe-like, 5-8 cm long, fleshy, yellowish, splitting open into 2 halves when ripe, containing 1 seed. Seed ovoid, 2-3 cm long, with a shiny dark brown, hard and stony, furrowed and longitudinally wrinkled shell, surrounded by a laciniate red aril which is attached to its base; kernel with small embryo and ruminate endosperm which contains many veins containing essential oil. The mace of commerce is the dried aril and the nutmeg is the dried kernel of the seed, often called nut.

Image

| Myristica fragrans Houtt. — 1, flowering and fruiting branch; 2, opened female flower; 3, staminal column; 4, seed with aril; 5, seed without aril; 6, section through seed without aril |

Growth and Development

Nutmeg seeds should be planted immediately after collecting, before they dry out. Seed in the shell takes some 4-6 weeks to germinate; without shell it may germinate in half that time. Vigorously growing trees may reach an average height of 3 m and a girth at 40 cm height of 16 cm in 4 years. Nutmeg is a slow grower, but growth can continue for up to 60-80 years; full production is reached in 15-20 years. Depending on the soil and climate a tree may ultimately reach a height of 20 m and occupy 100 m2. Under continuously per-humid or humid conditions, development of new shoots and leaves is also continuous.

The tree is characterized by a very superficial root system, although it may form a taproot penetrating the soil for over 10 m, provided it reaches no water table. Such a pen root does not develop in vegetatively propagated trees.

Usually a tree takes 6 years until first flowering, but if growing vigorously this period may be shortened to 4 years. In female trees a positive correlation exists between trunk diameter of young trees and later productivity. Male trees have a slightly smaller diameter, so keeping only the largest saplings may reduce the percentage of male trees. Flowering is probably induced by short dry periods. Anthesis is usually in the very early morning (3-5 a.m.) and pollination is normally effectuated by insects, especially moths. The fruit develops in 6 months if few fruits are growing, but takes up to 9 months if there are many fruits on the tree. Fruiting is more seasonal in regions with a pronounced dry season. Nutmeg is not strictly dioecious. Male trees show different degrees of femaleness, varying from no fruits at all to as many fruits as a good female tree.

The tree is characterized by a very superficial root system, although it may form a taproot penetrating the soil for over 10 m, provided it reaches no water table. Such a pen root does not develop in vegetatively propagated trees.

Usually a tree takes 6 years until first flowering, but if growing vigorously this period may be shortened to 4 years. In female trees a positive correlation exists between trunk diameter of young trees and later productivity. Male trees have a slightly smaller diameter, so keeping only the largest saplings may reduce the percentage of male trees. Flowering is probably induced by short dry periods. Anthesis is usually in the very early morning (3-5 a.m.) and pollination is normally effectuated by insects, especially moths. The fruit develops in 6 months if few fruits are growing, but takes up to 9 months if there are many fruits on the tree. Fruiting is more seasonal in regions with a pronounced dry season. Nutmeg is not strictly dioecious. Male trees show different degrees of femaleness, varying from no fruits at all to as many fruits as a good female tree.

Other Botanical Information

Myristica fragrans is a very variable species, morphologically and chemically. Although there are no officially registered cultivars there are many local cultivars (e.g. Rumphius distinguished 5 cultivars). Like many members of Myristicaceae, a wounded nutmeg tree exudes a light red, sticky sap (kino). Such bleeding seems to exhaust the tree.

Ecology

Nutmeg needs a warm and humid tropical climate, with average temperatures of 25-30°C and average annual rainfall of 2000-3500 mm without any real dry period. Flowering can be adversely affected by temperatures above 35°C and by hot dry winds. Frost always damages or kills the tree and makes commercial production impossible. Therefore, in the tropics the crop can only be grown below 700 m altitude. The superficial root system makes the tree very susceptible to wind damage. The crop can grow on any kind of soil provided there is sufficient water but without any risk of waterlogging. Preferred soils are those of volcanic origin and soils with a high content of organic matter with pH 6.5-7.5.

Propagation and planting

Nutmeg is usually propagated by seed, resulting in equal numbers of male and female trees. The seedlings reveal their sex at first flowering, which usually occurs some 6 years after planting. Therefore 2-3 seedlings are usually planted on the same spot. Male trees are then cut out and excess female trees may be transplanted to positions where there are no female trees. It is generally thought that to optimize production in plantations, only 10% of the trees should be male trees. Male trees should be distributed regularly through the plantation to secure pollination.

Several techniques have been tried to determine the sex of seeds or seedlings at an early stage, in order to prevent planting excess male seedlings. The oldest recorded method was to feed the fruits to pigeons, in the belief that the sex of the pigeon who ate and excreted the seed would then determine the sex of the tree. The form and venation of leaves, shape of seeds and form of branches have also received attention. First reports, however, were never followed by conclusive later publications. There has been a search for sex chromosomes that would enable young seedlings to be sexed. The hypothesis has been put forward that the female sex is heterogametic to the effect that 4 of the supposed 8 sex-chromosomes exhibit facultative nucleolar properties. This is especially evident in female meiosis where these 4 chromosomes orientate to one side. This is not the case in male meiosis. If it were true, seedlings could be 'sexed' by counting the chromosomes with facultative nucleolar properties in growing root tips. This hypothesis, however, has not been tested in practice, as the chromosomes are very small (0.4-1 µm) and isodiametric, so sexing would require skill and experience.

Planting distance for full-grown trees should be around 10 m x 10 m. Trees reach this size only after some 20 years of growth. Normally, however, trees are planted at approximately 6 m x 6 m and thinned later as the need arises. In areas with strong winds, protective measures should be taken.

Other methods of propagation have been developed to circumvent the problem of dioecy. Air layering was developed in Grenada. After about 3-5 months the rooted watershoot is cut off and planted in a nursery. After a period of growth it is hardened off and planted in the field. This method succeeds in 60-70% of cases. Another more successful method, also developed in Grenada is approach grafting. In this method the rootstock is hung in a pot in an especially selected mother tree. Other methods, such as budding on (male) seedlings or on other species of the same family have also been tried; they are usually less successful and there are no reports on their long-term results. Propagation by tissue culture is possible but is relatively expensive.

Several techniques have been tried to determine the sex of seeds or seedlings at an early stage, in order to prevent planting excess male seedlings. The oldest recorded method was to feed the fruits to pigeons, in the belief that the sex of the pigeon who ate and excreted the seed would then determine the sex of the tree. The form and venation of leaves, shape of seeds and form of branches have also received attention. First reports, however, were never followed by conclusive later publications. There has been a search for sex chromosomes that would enable young seedlings to be sexed. The hypothesis has been put forward that the female sex is heterogametic to the effect that 4 of the supposed 8 sex-chromosomes exhibit facultative nucleolar properties. This is especially evident in female meiosis where these 4 chromosomes orientate to one side. This is not the case in male meiosis. If it were true, seedlings could be 'sexed' by counting the chromosomes with facultative nucleolar properties in growing root tips. This hypothesis, however, has not been tested in practice, as the chromosomes are very small (0.4-1 µm) and isodiametric, so sexing would require skill and experience.

Planting distance for full-grown trees should be around 10 m x 10 m. Trees reach this size only after some 20 years of growth. Normally, however, trees are planted at approximately 6 m x 6 m and thinned later as the need arises. In areas with strong winds, protective measures should be taken.

Other methods of propagation have been developed to circumvent the problem of dioecy. Air layering was developed in Grenada. After about 3-5 months the rooted watershoot is cut off and planted in a nursery. After a period of growth it is hardened off and planted in the field. This method succeeds in 60-70% of cases. Another more successful method, also developed in Grenada is approach grafting. In this method the rootstock is hung in a pot in an especially selected mother tree. Other methods, such as budding on (male) seedlings or on other species of the same family have also been tried; they are usually less successful and there are no reports on their long-term results. Propagation by tissue culture is possible but is relatively expensive.

Husbandry

Young nutmeg plants are usually planted under 50% shade. With increasing age this shade can be reduced progressively and after 6-7 years the plants can grow without any shade at all, provided the soil is covered well, preferably by a cover crop.

Flowers are formed on young tops of branches, so in order not to hamper flowering the branches should not touch other trees.

Well-spaced trees may continue production for over 80 years. In nutmeg groves the lower branches usually are cut off to facilitate collection of dropped seeds, but if left on the tree, these branches would remain productive.

Very little is known on fertilizer application. Usually no fertilizer is used. On the island of Banda, plantations on volcanic soils have remained productive for hundreds of years.

Flowers are formed on young tops of branches, so in order not to hamper flowering the branches should not touch other trees.

Well-spaced trees may continue production for over 80 years. In nutmeg groves the lower branches usually are cut off to facilitate collection of dropped seeds, but if left on the tree, these branches would remain productive.

Very little is known on fertilizer application. Usually no fertilizer is used. On the island of Banda, plantations on volcanic soils have remained productive for hundreds of years.

Diseases and Pests

The only fungal disease of major importance is Stigmina myristicae (syn. Coryneum myristicae), a dry rot that causes the fruits to open when still young. Consequently the arils and seeds remain underdeveloped and are worthless. The conidia are spread by wind and rain. Another disease in nutmeg plantations is soft rot of fruits caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides; it also causes young unripe fruits to open prematurely. Root rots, caused by Fomes noxius and Fomes lamaoensis may cause considerable damage.

The most serious pest is the scolytid beetle Phloeosinus ribatus which bores through bark and cambium above and below ground level, causing dieback and death; this insect is blamed for the collapse of nutmeg production in Singapore and Pinang in the 1860s; other damaging borers are Xyleborus fornicatus and X. myristicae. Larvae of Stephanoderes moschatae and Dacryphalus sumatranus attack the nutmeg itself, resulting in the wormy seeds used for nutmeg butter and oil. The coffee bean weevil Ataecerus fasciculatus is the most serious pest of stored nutmeg and mace. Except for the use of lime in Indonesia, chemical control of diseases and pests is rarely practised as it is too expensive for smallholders and the degree of economic damage is usually too small to warrant control.

The most serious pest is the scolytid beetle Phloeosinus ribatus which bores through bark and cambium above and below ground level, causing dieback and death; this insect is blamed for the collapse of nutmeg production in Singapore and Pinang in the 1860s; other damaging borers are Xyleborus fornicatus and X. myristicae. Larvae of Stephanoderes moschatae and Dacryphalus sumatranus attack the nutmeg itself, resulting in the wormy seeds used for nutmeg butter and oil. The coffee bean weevil Ataecerus fasciculatus is the most serious pest of stored nutmeg and mace. Except for the use of lime in Indonesia, chemical control of diseases and pests is rarely practised as it is too expensive for smallholders and the degree of economic damage is usually too small to warrant control.

Harvesting

Harvesting is possible year-round in non-seasonal climates; in seasonal climates some peaks may occur. In Indonesia, especially on Banda, fruits are harvested when they are open. Harvesting is done with a small basket on a long pole, to which a sharpened piece of iron is attached. In Grenada seeds with attached aril are collected after they have dropped from the split fruit. Mace on the ground is very easily infested by all kinds of small animals and insects. The labour-intensive way of harvesting in Indonesia diminishes losses, especially of mace.

Yield

Annual production per female tree differs widely: excellent trees may produce yearly about 5000 fruits but trees with about 1000 fruits are fairly common. With 250 female trees per ha (spacing 6 m x 6 m) and at 5 g per dry shelled seed, nutmeg production is about 1250 kg/ha. At an air-dry weight ratio of 1 mace to 4 nutmegs, mace production reaches approximately 300 kg/ha.

Outside Banda and Grenada, however, nutmeg is only grown in small numbers by smallholders. There are hardly any yield figures available for such plantings.

Outside Banda and Grenada, however, nutmeg is only grown in small numbers by smallholders. There are hardly any yield figures available for such plantings.

Handling After Harvest

After harvest the seed is removed from the fruit and subsequently the aril is separated from the seed. The seed is dried, often above a slow-burning and smoking fire or, if only small quantities are available, in the sun. The fire deters insect attack. In the sun there is a danger of overheating, through which the fat in the seed may melt, resulting in broken kernels at shelling. When properly dried the kernel rattles in the shell. Then the shell is cracked to free the dry kernel (the nutmeg). Nutmegs from Indonesia are often white because they have been treated with lime, to protect against insect attack. Nutmegs are graded according to quality, size and weight. A number of commercially accepted grades are recognized. In Indonesia and Grenada sound nutmegs are graded as 80s or 110s, according to size in numbers per pound (lb, 454 g). Mixtures of sizes are exported as 'sound unsorted'. Alternatively, in Indonesia nutmeg is graded into 5 groups according to the number of nuts per 500 g: A (75-80), B (80-90), C (90-105), D (105-125) and E (125-160). Indonesia also exports substandard nutmegs of 2 types: 'sound shrivelled' and 'BWP' (broken, wormy and punky). Indonesia exports 2 grades for essential-oil distillation, containing 8-10% essential oil and 12-13% essential oil, respectively.

The aril is also dried, mostly in the sun, to give the mace of commerce. After drying it is stored in the dark to change its colour from the original red to orange-yellow. It is also sorted into different qualities, mainly whole, broken and fine.

The aril is also dried, mostly in the sun, to give the mace of commerce. After drying it is stored in the dark to change its colour from the original red to orange-yellow. It is also sorted into different qualities, mainly whole, broken and fine.

Genetic Resources

Myristica fragrans is not known in a wild state. The largest variability is probably found in Banda and a number of close relatives occur on the neighbouring islands. All other plantings throughout the world have been derived originally from plants from this region. There are no known substantial germplasm collections.

Breeding

The slow-growing female trees possess only 1-ovuled flowers. This makes the nutmeg a difficult target for breeding. However, the very limited market for nutmeg products makes breeding efforts uneconomical. As is to be expected in a predominantly outbreeding plant, the variability is great. Plants differ considerably, not only in such aspects as vigour, productivity and sex-ratio, but also in size, colour and shape of leaves, flowers and fruits. In 1940 selection programmes started in Indonesia, but the results were lost during the second World War. In Grenada, some promising trees have been brought together in special plantings. Quick results will probably be achieved by selection and vegetative propagation of highly productive females.

Prospects

The present annual world consumption of nutmeg and mace (some 20 000 t) could be produced on a well-managed 20 000 ha, and possibly even less. Unless the demand expands, there are few prospects for improved or increased production.

Literature

Ehlers, D., Kirchhoff, J., Gererd, D. & Quirin, K.W., 1998. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis of nutmeg and mace oils produced by supercritical CO2 extraction - comparison with steam-distilled oils - comparison of East Indian, West Indian and Papuan oils. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 33: 215-223.

Flach M., 1966. Nutmeg cultivation and its sex-problem; an agronomical and cytogenetical study of the dioecy in Myristica fragrans Houtt. and Myristica argentea Warb. Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool No 66-1. Wageningen Agricultural University, the Netherlands. 87 pp.

Flach, M. & Cruickshank, A.M., 1969. Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans Houtt. and Myristica argentea Warb.). In: Ferwerda, F.P. & Wit, F. (Editors): Outlines of perennial crop breeding in the tropics. Miscellaneous Papers No 4, Landbouwhogeschool, Wageningen Agricultural University, Wageningen, the Netherlands. pp. 329-338.

Janse, J.M., 1898. De nootmuskaatcultuur in de Minahassa en op het eiland Banda [Nutmeg cultivation in North Sulawesi and on Banda island]. Mededeelingen uit 's Lands Plantentuin, Buitenzorg 28: 1-230.

Nichols, R. & Cruickshank, A.M., 1964. Vegetative propagation of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) in Grenada, West Indies. Tropical Agriculture, Trinidad 41(2): 141-146.

Reddy, D.B., 1977. Pests, diseases and nematodes of major spices and condiments in Asia and the Pacific. Technical Document No 108. Plant Protection Committee for the Southeast Asia and Pacific Region. FAO, Rome, Italy. pp. 13-14.

Sinclair, J., 1958. A revision of the Malayan Myristicaceae. The Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 16: 205-472.

Sinclair, J., 1968. The genus Myristica in Malesia and outside Malesia. Florae Malesianae precursores 42. The Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 23: 1-540.

Weiss, E.A., 1997. Essential oil crops. Chapter 7: Myristicaceae. CAB International, Wallingford, Oxon, United Kingdom. pp. 214-234.

Flach M., 1966. Nutmeg cultivation and its sex-problem; an agronomical and cytogenetical study of the dioecy in Myristica fragrans Houtt. and Myristica argentea Warb. Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool No 66-1. Wageningen Agricultural University, the Netherlands. 87 pp.

Flach, M. & Cruickshank, A.M., 1969. Nutmeg (Myristica fragrans Houtt. and Myristica argentea Warb.). In: Ferwerda, F.P. & Wit, F. (Editors): Outlines of perennial crop breeding in the tropics. Miscellaneous Papers No 4, Landbouwhogeschool, Wageningen Agricultural University, Wageningen, the Netherlands. pp. 329-338.

Janse, J.M., 1898. De nootmuskaatcultuur in de Minahassa en op het eiland Banda [Nutmeg cultivation in North Sulawesi and on Banda island]. Mededeelingen uit 's Lands Plantentuin, Buitenzorg 28: 1-230.

Nichols, R. & Cruickshank, A.M., 1964. Vegetative propagation of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans) in Grenada, West Indies. Tropical Agriculture, Trinidad 41(2): 141-146.

Reddy, D.B., 1977. Pests, diseases and nematodes of major spices and condiments in Asia and the Pacific. Technical Document No 108. Plant Protection Committee for the Southeast Asia and Pacific Region. FAO, Rome, Italy. pp. 13-14.

Sinclair, J., 1958. A revision of the Malayan Myristicaceae. The Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 16: 205-472.

Sinclair, J., 1968. The genus Myristica in Malesia and outside Malesia. Florae Malesianae precursores 42. The Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 23: 1-540.

Weiss, E.A., 1997. Essential oil crops. Chapter 7: Myristicaceae. CAB International, Wallingford, Oxon, United Kingdom. pp. 214-234.

Author(s)

M. Flach & M. Tjeenk Willink

Correct Citation of this Article

Flach, M. & Tjeenk Willink, M., 1999. Myristica fragrans Houtt.. In: de Guzman, C.C. and Siemonsma, J.S. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 13: Spices. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.