Record Number

591

PROSEA Handbook Number

13: Spices

Taxon

Piper nigrum L.

Protologue

Sp. pl.: 28 (1753).

Family

PIPERACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 52 (occasionally other numbers have been reported, including 2n = 48, 104, 128)

Synonyms

Piper aromaticum Lamk (1791).

Vernacular Names

Pepper, black pepper (En). Poivre (Fr). Indonesia: lada, merica. Malaysia: lada. Papua New Guinea: daka. Philippines: paminta, paminta-liso (Cebuano), pamienta (Ilocano). Burma (Myanmar): ngayok-kaung. Cambodia: mréch. Laos: ph'ik no:yz, ph'ik th'ai. Thailand: phrik-thai (central), phrik-noi (northern). Vietnam: ti[ee]u, h[oof] ti[ee]u.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Pepper is native to the Western Ghats of Kerala State, India, where it still occurs wild in the mountains. Pepper reached South-East Asia as early as 100 BC, brought by Hindu colonists migrating from India to Indonesia and other countries. In about 1930, Japanese immigrants who had travelled through South-East Asia introduced the plant into Para State of northern Brazil, where it became a major crop.

In India, Indonesia and Malaysia, there is a long-established tradition of commercial cultivation by smallholders. The main areas of production in Indonesia are Lampung, Bangka and East and West Kalimantan, together accounting for 95% of the crop. Early in the 19th Century, pepper also spread to Sarawak, where nowadays 95% of the Malaysian crop is produced. In the 1990s Sri Lanka and China overtook Malaysia in pepper production, while Thailand and Vietnam also became important producers.

In India, Indonesia and Malaysia, there is a long-established tradition of commercial cultivation by smallholders. The main areas of production in Indonesia are Lampung, Bangka and East and West Kalimantan, together accounting for 95% of the crop. Early in the 19th Century, pepper also spread to Sarawak, where nowadays 95% of the Malaysian crop is produced. In the 1990s Sri Lanka and China overtook Malaysia in pepper production, while Thailand and Vietnam also became important producers.

Uses

Black and white pepper are the two main dried commodities growers prepare from the fruits of Piper nigrum. The use of the dried product as a food flavouring was already known in classical Rome and Europe was an important importer of pepper as early as the 12th Century. About 80% of the pepper consumption is now concentrated in the industrially developed countries, where it is mainly used for domestic culinary purposes and for flavouring and preserving processed foods. There is a remarkable lack of tradition in the consumption of both types of pepper in Indonesia, Malaysia and adjacent countries of South-East Asia. In recent decades, its classic use as a spice in food flavouring and preservation has increased gradually in these countries because of expanding tourism and industrial development. However, most of the production is still exported. In India and Sri Lanka, domestic consumption for food flavouring is common tradition. Pepper oil and pepper oleoresin, extractable from peppercorns, are mainly used in the production of convenience foods. Of secondary importance is the use of preserved immature green pepper or fresh green pepper fruits. In the United States the regulatory status 'generally recognized as safe' has been accorded to black pepper (GRAS 2844), black pepper oil (GRAS 2845) and black pepper oleoresin (GRAS 2846). The same applies to white pepper (GRAS 2850), white pepper oil (GRAS 2851) and white pepper oleoresin (GRAS 2852). The maximum permitted level of the oils in food products is about 0.04%.

Production and International Trade

No distinction is made between black and white pepper in trade statistics. Between 1985 and 1997, annual world production of pepper fluctuated from 140 000-280 000 t. Production peaked in 1990. The area planted worldwide in 1997 was about 365 000 ha, with 200 000 ha in India, 75 000 ha in Indonesia, 26 000 ha in Sri Lanka, 12 000 ha in Brazil, 12 000 ha in China and 10 000 ha in Malaysia. World production in 1997 amounted to 215 000 t, with 62 000 t from India, 50 000 t from Indonesia, 17 000 t from Sri Lanka, 22 000 t from Brazil, 14 000 t from China and 12 000 t from Malaysia. By 1997 the acreage and production had reportedly increased to 3600 ha and 12 000(!) t in Thailand, and to 7500 ha and 11 000 t in Vietnam.

Annual world exports during 1988-1993 ranged from 172 000-242 000 t. The major exporters were India, Singapore, Indonesia, Brazil and Malaysia. Singapore serves mainly as an entrepôt. The value of world exports from 1988 to 1993 ranged from US$ 270-569 million per year. The highest revenue was in 1988, the year with the lowest export in terms of tonnage. The major importers were the United States, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Japan and the United Kingdom. Imports ranged from 174 000-216 000 t valued at US$ 273-658 million.

Annual world exports during 1988-1993 ranged from 172 000-242 000 t. The major exporters were India, Singapore, Indonesia, Brazil and Malaysia. Singapore serves mainly as an entrepôt. The value of world exports from 1988 to 1993 ranged from US$ 270-569 million per year. The highest revenue was in 1988, the year with the lowest export in terms of tonnage. The major importers were the United States, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Japan and the United Kingdom. Imports ranged from 174 000-216 000 t valued at US$ 273-658 million.

Properties

Dried peppercorns (black pepper) contain per 100 g edible portion: water 9.5-12.0 g, protein 10.9-12.7 g, starch 25.8-44.8 g, fibre 9.7-17.2 g, and ash 3.4-6.0 g. White pepper contains per 100 g edible portion: water 9.5-13.7 g, protein 10.7-12.4 g, starch 53.9-60.4 g, fibre 3.5-4.5 g, and ash 1.0-2.8 g. With the energy value averaging 1300 kJ/100 g and a very small daily intake, the nutritional value is negligible.

Flavour and pungency differ for black and white pepper, and tend to vary with region and cultivar. Pepper is highly popular for its piquant flavour and pungency and distinctive aroma. Piperine, C17H19O3N, is the chief pungent principle, its content varying from 4.9-7.7% in black pepper and 5.5-5.9% in white pepper. Essential oil is also an important constituent of pepper, being responsible for the characteristic odour. In commercial cultivars its content ranges from 1.0-1.8% in black pepper to 0.5-0.9% in white pepper. About 90% of the essential oil consists of monoterpene and sesquiterpene hydrocarbons.

A monograph on the physiological properties of black pepper oil has been published by the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM).

The weight of 100 peppercorns is (3-)4.5(-8) g.

Flavour and pungency differ for black and white pepper, and tend to vary with region and cultivar. Pepper is highly popular for its piquant flavour and pungency and distinctive aroma. Piperine, C17H19O3N, is the chief pungent principle, its content varying from 4.9-7.7% in black pepper and 5.5-5.9% in white pepper. Essential oil is also an important constituent of pepper, being responsible for the characteristic odour. In commercial cultivars its content ranges from 1.0-1.8% in black pepper to 0.5-0.9% in white pepper. About 90% of the essential oil consists of monoterpene and sesquiterpene hydrocarbons.

A monograph on the physiological properties of black pepper oil has been published by the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM).

The weight of 100 peppercorns is (3-)4.5(-8) g.

Adulterations and Substitutes

Common adulterants of whole or ground pepper are pepper of lower quality and various foreign matter. Synthetic compounds or isolates of volatiles from cheaper sources are used to adulterate pepper essential oil.

Description

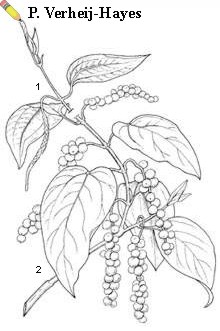

A perennial woody climber, up to 10 m long or more. In cultivation, mature plants grown on supports may also appear as bushy columns, 3-4 m tall and 1.25 m in diameter. Root system with 5-20 main roots, 4 m or more deep, and with feeder roots in the upper 60 cm of soil, which form an extensive dense mat. Orthotropic stems climbing and remaining vegetative, adhering to supports with short adventitious roots present at the nodes, internodes 5-12 cm long and 4-6 cm in diameter. Plagiotropic branches generative, without adventitious roots, internodes 4-6 cm long and 1-1.5 cm in diameter, producing higher-order branches as well as inflorescences. Leaves alternate, simple, glabrous, coriaceous, petiolate; petiole 2-5 cm long; blade ovate, 8-20 cm x 4-12 cm, entire, oblique to rounded at base, tip acuminate, shiny dark green above, pale and densely glandular-dotted beneath with 5-7 veins. Inflorescence a spike, appearing opposite the leaves on plagiotropic branches, 3-15 cm long with 50-150 flowers; flowers unisexual or bisexual (cultivars usually have up to 90% bisexual flowers), without perianth, stamens 2-4, stigma with 3-5 lobes. Fruit a globose drupe, 4-6 mm in diameter, sessile, with pulpy mesocarp, red when mature. Seed globose, 3-4 mm in diameter.

Image

| Piper nigrum L. — 1, twig with young inflorescence; 2, fruiting branch |

Growth and Development

Ripe shade-dried seed of pepper without mesocarp germinates in 2-3 weeks, but commercial propagation is only by cuttings. The vegetative development of planted cuttings proceeds with the formation of several orthotropic shoots from axillary buds; only during active growth may primary lateral branches develop on the nodes. A few early spikes may appear on the lateral branches. Continuous branching gives rise to the bushy habit, and when vigorous growth is stimulated, regular growth of orthotrophic stems and development of plagiotropic branches allows large numbers of spikes to be formed at the onset of the rains.

In South-East Asia, flowering starts in July in the Philippines, and September in Sarawak, followed by Bangka and Lampung; it usually extends over about three months. Spikes show protogynous development from base to tip. Geitonogamy (autogamous pollination that results from the transfer of pollen between different flowers on the same individual) is believed to be the common mode of pollination. Self-pollination by wind is rare. High relative humidity may extend stigma receptivity from 8-13 days and thus promote self-pollination. Heavy rains, storms and long sunny days may reduce fertilization, while light intermittent rain and showery conditions may increase fruit set. After fertilization, the ovary develops into a mature fruit in 8-9 months. Fruit development is accelerated by well-distributed rainfall and the presence of balanced minerals, especially potassium and magnesium. Pepper plants can produce abundantly for up to 30 years.

If stolons or suckers are used for planting, spike formation will be retarded by 2 years, because the formation of lateral branches on the orthotropic stem is delayed.

In South-East Asia, flowering starts in July in the Philippines, and September in Sarawak, followed by Bangka and Lampung; it usually extends over about three months. Spikes show protogynous development from base to tip. Geitonogamy (autogamous pollination that results from the transfer of pollen between different flowers on the same individual) is believed to be the common mode of pollination. Self-pollination by wind is rare. High relative humidity may extend stigma receptivity from 8-13 days and thus promote self-pollination. Heavy rains, storms and long sunny days may reduce fertilization, while light intermittent rain and showery conditions may increase fruit set. After fertilization, the ovary develops into a mature fruit in 8-9 months. Fruit development is accelerated by well-distributed rainfall and the presence of balanced minerals, especially potassium and magnesium. Pepper plants can produce abundantly for up to 30 years.

If stolons or suckers are used for planting, spike formation will be retarded by 2 years, because the formation of lateral branches on the orthotropic stem is delayed.

Other Botanical Information

In the wild, Piper nigrum is mostly dioecious and morphologically rather variable. Piper nigrum cultivars are usually bisexual. In its country of origin, India, there are more than 75 cultivars. Some well-known Indian pepper cultivars are: 'Balamcotta' (leaves large, light green; fruit yield regular and high); 'Kalluvalli' (leaves narrower, dark green; drought and wilt resistant; bearing regular); 'Cheria Kaniakadan' (leaves small, elliptical; wilt-resistant; regular and heavy bearer; unsuccessful in Sarawak, where it was unisexual). In Indonesia, more than 5 cultivars of pepper are commercially produced. The major cultivars in Lampung are 'Kerenci', 'Belantung' and 'Jambi'. On Bangka, the cultivars 'Lampung' (broad leaf) and 'Bangka' are popular. Differences are mainly in leaf shape and size, internode length, branching habit and flowering and fruiting ability. In Malaysia (Sarawak) the dense-branching high-yielding cultivar 'Kuching' is most popular. It has large leaves and is very susceptible to foot-rot. 'Sarikei' is a smaller-leaved cultivar. In Cambodia 'Phnom-Pon' is a large-leaved cultivar, 'Kamchay' a small-leaved one.

Ecology

The most suitable climate for pepper is per-humid tropical, with a well-distributed annual rainfall of 2000-4000 mm associated with a mean air temperature of 25-30°C and a relative humidity of 65-95%. In Sarawak, annual rainfall may exceed 4000 mm in a non-seasonal climate, whereas on Bangka an average of 2500 mm is usual. In Lampung, the crop grows well in the north with over 3000 mm annual rainfall and in the south-east with sometimes less than 2000 mm. A drier period of 2-3 months, with a monthly rainfall of 60-80 mm, is not usually harmful. The crop thrives below 500 m altitude on the equator, but may grow at altitudes as high as 1500 m.

Pepper grows well on soils ranging from heavy clay to light sandy clays. Soils should be deep, well-drained but with ample water-holding capacity to avoid water stress during marked dry periods. Mineral limitations are common, except on virgin soils. In brown-red latosols, N, P and Mg are often limiting. In physically suitable red-yellow podzols, deficiencies of most major and minor elements are not exceptional, with too high acidity and excess Al at pH below 5. The most favourable soil types are deep, well-drained, brown-red latosols or andosols, but the crop can grow well on deep sandy clay red-yellow podzols if carefully managed and amply provided with mineral nutrients and organic matter.

Pepper grows well on soils ranging from heavy clay to light sandy clays. Soils should be deep, well-drained but with ample water-holding capacity to avoid water stress during marked dry periods. Mineral limitations are common, except on virgin soils. In brown-red latosols, N, P and Mg are often limiting. In physically suitable red-yellow podzols, deficiencies of most major and minor elements are not exceptional, with too high acidity and excess Al at pH below 5. The most favourable soil types are deep, well-drained, brown-red latosols or andosols, but the crop can grow well on deep sandy clay red-yellow podzols if carefully managed and amply provided with mineral nutrients and organic matter.

Propagation and planting

Most cultivars of pepper are propagated by cuttings. Early in the wet season, usually pre-topped 5-7 cm long pieces of terminal orthotropic shoots are taken from vigorous plants 12-30 months old. Cuttings can be rooted in a moist medium in a shaded nursery. Ample roots should have appeared after about 2 months. Sometimes cuttings are directly planted in the field. Though easier to root, stolons or runners are less suitable as planting material than terminal orthotropic shoots because they bear fruit late, about 3 years from planting. Micropropagation through shoot-tip culture has also been reported.

Before planting, the land is cleared, tilled and hoed. Hardwood supports 3.60 m high are placed at 2-4 m x 2-4 m. In poor soils, the topsoil is mounded around the base of the supports. In rich soils, planting is usually directly into loosened topsoil.

If trees are used as support, stumps are planted at the required spacing about one year before the rooted cuttings are set in the field. Cuttings are transplanted to the field during a rainy period and usually receive temporary shade. One to two months later, growth becomes vigorous.

In Sarawak, West and East Kalimantan and on Bangka, an intensive system of sole cropping on dead posts and without shade prevails. It is characteristically associated with chemically poor soils, high inputs and high productivity. In Lampung, cultivation of pepper against living Erythrina shade trees (up to 10 m tall) predominates and is characterized by fertile soils, low inputs and low productivity. In the Philippines, Gliricidia support trees are commonly used. Intercropping is rare in the system using shade, although it occurs in smallholdings in the Philippines. In several countries, pepper is planted as an intercrop in coconut and coffee plantations.

Before planting, the land is cleared, tilled and hoed. Hardwood supports 3.60 m high are placed at 2-4 m x 2-4 m. In poor soils, the topsoil is mounded around the base of the supports. In rich soils, planting is usually directly into loosened topsoil.

If trees are used as support, stumps are planted at the required spacing about one year before the rooted cuttings are set in the field. Cuttings are transplanted to the field during a rainy period and usually receive temporary shade. One to two months later, growth becomes vigorous.

In Sarawak, West and East Kalimantan and on Bangka, an intensive system of sole cropping on dead posts and without shade prevails. It is characteristically associated with chemically poor soils, high inputs and high productivity. In Lampung, cultivation of pepper against living Erythrina shade trees (up to 10 m tall) predominates and is characterized by fertile soils, low inputs and low productivity. In the Philippines, Gliricidia support trees are commonly used. Intercropping is rare in the system using shade, although it occurs in smallholdings in the Philippines. In several countries, pepper is planted as an intercrop in coconut and coffee plantations.

Husbandry

In unshaded intensive cropping of pepper, husbandry mainly includes weeding, mounding, topping of stem shoots, pruning for regular shape, manuring and disease and pest control. In Sarawak, clean-weeding is common. Mounds are maintained to provide ample room for dense rooting. During times of rapid growth, stems are tied to the posts weekly. Pruning aims to maximize the number of fruiting branches. Usually three stems are allowed to climb up the post. When 60-90 cm long, each is pruned back, usually to just below the lowest stem node without lateral branch, leaving 3-4 nodes, each with a fruiting branch. This process is repeated regularly, stimulating secondary and higher-order branching. After 30 months, plants are 2.5 m tall, have a bushy appearance with the maximum number of main branches and a close canopy. The plants may now be considered as full-grown and start flowering fully with the onset of the rains.

During vegetative development, vines on poor soils are supplied with complete fertilizer, usually with a content of 12% N, 5% P2O5, 17% K2O, 2% MgO and a range of minor elements. In the first year each plant receives 0.5 kg in 4 equal applications, in the second year 1 kg also in 4 equal applications. During the generative phase, each vine receives annual dressings of 1.5-2 kg, again divided over 4 applications. In the Philippines, fertilizer is applied only twice a year, at the onset and towards the end of the rainy season.

Intensive cropping in Indonesia is less elaborate than in Sarawak. Clean-weeding is usually done irregularly and manuring practised less precisely. To achieve bushy plants, stem shoots are allowed to grow freely to the top of the post. The stems are then bent down and trained in a circle around the post and their upper nodes are tied to the support. The results are generally less satisfactory than those in Sarawak, although precise application of this system on Bangka gave yields comparable to those in Sarawak. In Lampung, husbandry operations in shaded cropping are limited to irregular weeding and annual pruning of the shade trees.

During vegetative development, vines on poor soils are supplied with complete fertilizer, usually with a content of 12% N, 5% P2O5, 17% K2O, 2% MgO and a range of minor elements. In the first year each plant receives 0.5 kg in 4 equal applications, in the second year 1 kg also in 4 equal applications. During the generative phase, each vine receives annual dressings of 1.5-2 kg, again divided over 4 applications. In the Philippines, fertilizer is applied only twice a year, at the onset and towards the end of the rainy season.

Intensive cropping in Indonesia is less elaborate than in Sarawak. Clean-weeding is usually done irregularly and manuring practised less precisely. To achieve bushy plants, stem shoots are allowed to grow freely to the top of the post. The stems are then bent down and trained in a circle around the post and their upper nodes are tied to the support. The results are generally less satisfactory than those in Sarawak, although precise application of this system on Bangka gave yields comparable to those in Sarawak. In Lampung, husbandry operations in shaded cropping are limited to irregular weeding and annual pruning of the shade trees.

Diseases and Pests

The major destructive disease of pepper cultivars in Malaysia and Indonesia is a foot-rot, caused by the soilborne fungus Phytophthora palmivora MF 4, which thrives under warm and humid conditions. The disease may infect the leaves and the roots, underground stem and root collar. It usually arises after rains. Leaves, especially the lower ones, are infected through soil-splash, resulting in the formation of black necrotic spots with typical fringed margins. Affected leaves drop within a few days before the infection spreads to the stem. The leaf drop contributes to the build-up of the soil inoculum. Symptoms of rapid, almost uniform wilting of leaves are visible, especially towards the end of the rainy season. They result from blocked water vessels in the stem and increasing water stress. Infected vines die within days or weeks. Rapid spread in gardens is typical; infected gardens may be ruined within weeks up to a few months. No effective control measures, suitable for smallholders, are yet available. Current research aims at grafting susceptible cultivars onto a rootstock of resistant pepper species such as Piper colubrinum Link and at breeding for resistance.

A second significant disorder in South-East Asia is the slow wilt 'yellow disease' occurring mainly on Bangka. Symptoms include a slow wilting and associated yellowing and drooping of leaves. The disorder has been identified as a combination of poor mineral nutrition and root invasion by Radopholus nematodes. The decline may be well controlled by liberal dressings of complete and balanced mineral nutrients and by liming and mulching.

Other diseases and pests do occur in the region, but can be effectively controlled by simple treatments with suitable fungicides and insecticides.

A second significant disorder in South-East Asia is the slow wilt 'yellow disease' occurring mainly on Bangka. Symptoms include a slow wilting and associated yellowing and drooping of leaves. The disorder has been identified as a combination of poor mineral nutrition and root invasion by Radopholus nematodes. The decline may be well controlled by liberal dressings of complete and balanced mineral nutrients and by liming and mulching.

Other diseases and pests do occur in the region, but can be effectively controlled by simple treatments with suitable fungicides and insecticides.

Harvesting

In South-East Asia, pepper harvesting extends from April-June to August-September. This period generally coincides with dry weather and sunshine. To obtain black pepper, entire fruit spikes are picked when the fruits are full-grown and mature but still green (shiny yellowish green). For white pepper, fruit spikes are collected when a few fruits have turned red or yellow. Fruit spikes are harvested by hand, using a tripod ladder. Frequency of harvesting is usually 6-8 times per season (every 2 weeks); in some areas only twice or thrice. Whether black or white pepper is prepared may depend on the expected price of the product.

Yield

Assuming uninterrupted optimal conditions for commercial vines and no fatal diseases, unshaded pepper has an economic life of 15-20 years. This lifetime is reduced to 6-10 years by poor husbandry. Mean annual production of fresh fruits per plant varies from (2-)6-12(-18) kg in Sarawak to (0.5-)2-4(-8) kg on Bangka and in Kalimantan.

For shaded vines (as in Lampung, Indonesia, and in the Philippines), the life span may exceed 30 years. Assuming a minimum of agronomic attention, but fertile soil and absence of fatal diseases, mean annual production per plant reaches (4-)12(-20) kg of fresh fruits.

In 1997, average yields of dried peppercorns per ha per year ranged from 0.3 t/ha in India to 0.7 t/ha in Indonesia, 1.2 t/ha in Malaysia, and 1.9 t/ha in Brazil. The statistics for Vietnam and Thailand indicate yields of 1.4 t/ha and 3.3(!) t/ha respectively.

For shaded vines (as in Lampung, Indonesia, and in the Philippines), the life span may exceed 30 years. Assuming a minimum of agronomic attention, but fertile soil and absence of fatal diseases, mean annual production per plant reaches (4-)12(-20) kg of fresh fruits.

In 1997, average yields of dried peppercorns per ha per year ranged from 0.3 t/ha in India to 0.7 t/ha in Indonesia, 1.2 t/ha in Malaysia, and 1.9 t/ha in Brazil. The statistics for Vietnam and Thailand indicate yields of 1.4 t/ha and 3.3(!) t/ha respectively.

Handling After Harvest

Freshly picked fruit spikes of pepper are usually taken to the farmhouse for processing. To prepare black pepper, spikes are left in heaps overnight for brief fermentation. Next morning, the mass of spikes and fruits is usually spread out on bamboo mats or concrete floors to dry in the sun, and is raked regularly. Another option is to blanch spikes and dry them on a flat-bed dryer (this reduces the drying time to about 7 hours). The mesocarp shrinks and fruits separate from the rachis during raking. The fruits may also be threshed by treading or using a threshing machine. After 4-5 days, the peppercorns are black and dry, showing their typical crinkled appearance. Moisture content usually ranges between 10-14%. The dried peppercorns are bagged and stored, pending sale.

To prepare white pepper, the fruit spikes are lightly crushed, put in gunny sacks and soaked for 7-10 days, preferably in slow-running water. The mesocarp disintegrates with retting. After soaking, peppercorns are trampled loose from the spike and separated by washing and sieving. The washed peppercorns are dried in the sun for 3-4 days, during which the white to cream colour develops. The dry peppercorns, usually with a moisture content of 10-14%, are then bagged and stored. If stagnant water has been used for processing, the dried peppercorns assume a grey colour and release a musty odour.

The weight ratio white pepper/fresh fruits is about 26% and that of black pepper/fresh fruits 33%. The proportion of the crop processed into white pepper in Sarawak depends on the price differential with black pepper. In Indonesia, Bangka traditionally produces only white pepper and Lampung only black pepper. The Philippines generally produces black pepper.

Black pepper can be further processed into oleoresin and pepper oil. The pepper oleoresin is obtained by extraction with a suitable solvent. The spice equivalent of oleoresin is 1 : (20-25). Pepper oil is derived by steam distillation of ground pepper.

To prepare white pepper, the fruit spikes are lightly crushed, put in gunny sacks and soaked for 7-10 days, preferably in slow-running water. The mesocarp disintegrates with retting. After soaking, peppercorns are trampled loose from the spike and separated by washing and sieving. The washed peppercorns are dried in the sun for 3-4 days, during which the white to cream colour develops. The dry peppercorns, usually with a moisture content of 10-14%, are then bagged and stored. If stagnant water has been used for processing, the dried peppercorns assume a grey colour and release a musty odour.

The weight ratio white pepper/fresh fruits is about 26% and that of black pepper/fresh fruits 33%. The proportion of the crop processed into white pepper in Sarawak depends on the price differential with black pepper. In Indonesia, Bangka traditionally produces only white pepper and Lampung only black pepper. The Philippines generally produces black pepper.

Black pepper can be further processed into oleoresin and pepper oil. The pepper oleoresin is obtained by extraction with a suitable solvent. The spice equivalent of oleoresin is 1 : (20-25). Pepper oil is derived by steam distillation of ground pepper.

Genetic Resources

India is the primary gene centre for pepper, whereas the Amazon Region of Brazil is the primary gene centre for many other Piperaceae. Piper species have also been found in many countries of South-East Asia, South and Central America, and also Africa.

Small germplasm collections are maintained in Sarawak and in Indonesia. In 1981, the Sarawak gene pool included 18 cultivars of Piper nigrum, 18 identified Piper species, and 98 unidentified accessions. The collection is steadily being expanded. In 1985, the Indonesian gene pool included 40 cultivars of Piper nigrum and 7 Piper species. This collection too is being regularly expanded.

Small germplasm collections are maintained in Sarawak and in Indonesia. In 1981, the Sarawak gene pool included 18 cultivars of Piper nigrum, 18 identified Piper species, and 98 unidentified accessions. The collection is steadily being expanded. In 1985, the Indonesian gene pool included 40 cultivars of Piper nigrum and 7 Piper species. This collection too is being regularly expanded.

Breeding

Malaysia and Indonesia have high-yielding pepper cultivars, and breeding for better yield has low priority. All these cultivars are susceptible or highly susceptible to Phytophthora foot-rot disease. Development of resistant plant material is urgently required and is receiving high priority. At first some newly bred cultivars showed a certain degree of resistance or tolerance, but they merely slowed down infection and spread of the disease in gardens. Some new promising hybrids were developed, but they did not survive in the field. More recent results of hybridization, however, have shown encouraging prospects in terms of field resistance.

Another approach in plant improvement involves grafting onto well-tested rootstocks that are resistant to foot-rot. However, the grafts failed at about 6 years of age. In Indonesia, improved techniques for bud-grafting of woody stems and the development of a method for herbaceous budding are promising. Viable resistant buddings, combined with integrated disease-control measures, might overcome this major problem in pepper cultivation.

Another approach in plant improvement involves grafting onto well-tested rootstocks that are resistant to foot-rot. However, the grafts failed at about 6 years of age. In Indonesia, improved techniques for bud-grafting of woody stems and the development of a method for herbaceous budding are promising. Viable resistant buddings, combined with integrated disease-control measures, might overcome this major problem in pepper cultivation.

Prospects

World demand for pepper is rather inelastic, but is tending to increase at an average rate of 4-5% per year. So, production of pepper offers fairly attractive prospects for smallholders as a source of cash income. However, with the ever-present danger of sudden destruction of plantations by Phytophthora foot-rot, farmers in affected areas are tending to turn away from pepper cultivation. Only when supply of pepper falls short of world demand and prices become high may farmers be induced to take the risks of new planting.

The fluctuations in world production combined with an inelastic demand lead to fluctuations in price that are strongly aggravated by speculation by traders. Only when plant material resistant to foot-rot becomes available will development of agronomic methods for higher productivity and lower production costs be expedient. Overproduction might be overcome by judiciously planned reduction of areas with pepper in favour of alternative remunerative crops.

The fluctuations in world production combined with an inelastic demand lead to fluctuations in price that are strongly aggravated by speculation by traders. Only when plant material resistant to foot-rot becomes available will development of agronomic methods for higher productivity and lower production costs be expedient. Overproduction might be overcome by judiciously planned reduction of areas with pepper in favour of alternative remunerative crops.

Literature

Carlos Jr, J.T. & Balikrishnan, S., 1990. South Pacific spice production: development and prospects. Asian Development Bank, Institute for Research, Extension and Training in Agriculture, and Technical Center for Agricultural Rural Cooperation, Apia, Western Samoa. pp. 59-70.

Govindarajan, V.S., 1977. Pepper-chemistry, technology and quality evaluation. CRC Critical Reviews in Food Science & Technology 9(2): 115-225.

Keng, T.K., 1979. Pests, diseases and disorders of black pepper in Sarawak. Department of Agriculture, Sarawak, East Malaysia.

PCARRD, 1990. Philippines recommends for black pepper. Philippine Council for Agriculture, Forestry and Natural Resources Research and Development, Los Baños, Laguna, the Philippines. PCARRD Bulletin Series No 70.

Philip, V.J., Joseph, D., Triggs, G.S. & Dickinson, N.M., 1992. Micropropagation of black pepper (Piper nigrum Linn.) through shoot tip cultures. Plant Cell Reports 12: 41-44.

Purseglove, J.W., Brown, E.G., Green, C.L. & Robbins, S.R.J., 1981. Spices. Vol. 1. Longman, Harlow, Essex, United Kingdom. pp. 10-99.

Sim, S.L., Bong, C.F.J. & Mohd Said Saad (Editors), 1986. Origin, distribution and botany of pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Pepper in Malaysia. Proceedings of the National Conference on Pepper in Malaysia, 16-17 December 1985. Universiti Pertanian Malaysia, Kuching, Sarawak. pp. 17-24.

de Waard, P.W.F., 1980. Problem areas and prospects of production of pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Bulletin 308. Department of Agricultural Research, Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. 29 pp.

de Waard, P.W.F. & Zaubin, R., 1983. Callus formation during grafting of woody plants. A concept for the case of black pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Abstracts on Tropical Agriculture 9: 9-19.

de Waard, P.W.F. & Zeven, A.C., 1969. Pepper (Piper nigrum L.). In: Ferwerda, F.P. & Wit, F. (Editors): Outlines of perennial crop breeding in the tropics. Miscellaneous Papers 4, Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen, the Netherlands. pp. 409-426.

Govindarajan, V.S., 1977. Pepper-chemistry, technology and quality evaluation. CRC Critical Reviews in Food Science & Technology 9(2): 115-225.

Keng, T.K., 1979. Pests, diseases and disorders of black pepper in Sarawak. Department of Agriculture, Sarawak, East Malaysia.

PCARRD, 1990. Philippines recommends for black pepper. Philippine Council for Agriculture, Forestry and Natural Resources Research and Development, Los Baños, Laguna, the Philippines. PCARRD Bulletin Series No 70.

Philip, V.J., Joseph, D., Triggs, G.S. & Dickinson, N.M., 1992. Micropropagation of black pepper (Piper nigrum Linn.) through shoot tip cultures. Plant Cell Reports 12: 41-44.

Purseglove, J.W., Brown, E.G., Green, C.L. & Robbins, S.R.J., 1981. Spices. Vol. 1. Longman, Harlow, Essex, United Kingdom. pp. 10-99.

Sim, S.L., Bong, C.F.J. & Mohd Said Saad (Editors), 1986. Origin, distribution and botany of pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Pepper in Malaysia. Proceedings of the National Conference on Pepper in Malaysia, 16-17 December 1985. Universiti Pertanian Malaysia, Kuching, Sarawak. pp. 17-24.

de Waard, P.W.F., 1980. Problem areas and prospects of production of pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Bulletin 308. Department of Agricultural Research, Royal Tropical Institute, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. 29 pp.

de Waard, P.W.F. & Zaubin, R., 1983. Callus formation during grafting of woody plants. A concept for the case of black pepper (Piper nigrum L.). Abstracts on Tropical Agriculture 9: 9-19.

de Waard, P.W.F. & Zeven, A.C., 1969. Pepper (Piper nigrum L.). In: Ferwerda, F.P. & Wit, F. (Editors): Outlines of perennial crop breeding in the tropics. Miscellaneous Papers 4, Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen, the Netherlands. pp. 409-426.

Author(s)

P.W.F. de Waard & I.S. Anunciado

Correct Citation of this Article

de Waard, P.W.F. & Anunciado, I.S., 1999. Piper nigrum L.. In: de Guzman, C.C. and Siemonsma, J.S. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 13: Spices. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.