Record Number

6

PROSEA Handbook Number

2: Edible fruits and nuts

Taxon

Durio zibethinus Murray

Protologue

Syst. Nat. Veg. ed. 13: 581 (1774).

Family

BOMBACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 56

Synonyms

Durio acuminatissima Merr. (1926).

Vernacular Names

General name in all languages: durian. Indonesia: duren, ambetan (Javanese), kadu (Sundanese). Philippines: dulian (Sulu). Burma: du-yin. Cambodia: thu-réén. Laos: thourièn. Thailand: thurian (general), rian (southern Peninsula). Vietnam: sâù- riêng.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

The genus is native to South-East Asia and wild durian trees are found in Borneo and Sumatra. In cultivation the tree has been spread over an area ranging from Sri Lanka and South India to New Guinea. Only a few trees are found outside this area, namely in Australia, Hawaii and Zanzibar.

Durian is quite common throughout South-East Asia, but in the Philippines only in Mindanao, while in the rest of the country the trees are few and far between. It is also an important crop in Vietnam and Burma. The trees are mainly grown in homegardens and on field borders, where they belong to the upper storey of a rich mixture of trees; in Thailand durian is largely grown in orchards.

Durian is quite common throughout South-East Asia, but in the Philippines only in Mindanao, while in the rest of the country the trees are few and far between. It is also an important crop in Vietnam and Burma. The trees are mainly grown in homegardens and on field borders, where they belong to the upper storey of a rich mixture of trees; in Thailand durian is largely grown in orchards.

Uses

The ripe fruits, or rather the arils which form the edible part, are generally eaten fresh. In the market the fruit advertises itself by its strong and unmistakable smell. The fruit is liked so much that the rice harvest in Indonesia suffers if it coincides with the durian harvest, and during peak seasons people still their appetite eating durian. The fruit is preserved by drying the flesh into 'durian cake' or by boiling it with sugar; it may also be fermented or salted. Nowadays the arils are also shrink-wrapped and deep-frozen to extend the supply season; in this form the fruit is gaining acceptance in the export trade. Durian flavour is much liked in ice creams and cookies.

The boiled or roasted seeds are eaten as a snack. Young shoots and unripe fruit may be cooked as greens. The rind of the fruit is dried and used as fuel, in particular to smoke fish. Several parts of the tree are used medicinally; the fruit is supposed to restore the health of ailing humans and animals. According to popular belief, sickness and even death may strike people who consume durian in conjunction with alcohol. The coarse light wood is not durable, but is used for indoor construction and cheaper types of furniture.

The boiled or roasted seeds are eaten as a snack. Young shoots and unripe fruit may be cooked as greens. The rind of the fruit is dried and used as fuel, in particular to smoke fish. Several parts of the tree are used medicinally; the fruit is supposed to restore the health of ailing humans and animals. According to popular belief, sickness and even death may strike people who consume durian in conjunction with alcohol. The coarse light wood is not durable, but is used for indoor construction and cheaper types of furniture.

Production and International Trade

Thailand is the largest producer with 444 500 t in 1987/1988 from 84 700 ha. Indonesia is a good second with 200 000 t in 1985/1986. In Peninsular Malaysia area and production in 1987 were 42 000 ha and 262 000 t respectively. The Philippines recorded only 16 700 t in 1987 from 2030 ha. The export of fresh fruit from Thailand in 1987 (11 100 t) was worth US$ 9.5 million, Hong Kong's share being 65%, followed by the United States and France. Medium-size fruits (e.g. 2.5 kg per piece for 'Chanee') are preferred abroad and growers try to increase the proportion of fruit of that size. Large fruits of superior cultivars may fetch as much as US$ 4-5 each in Bangkok or Chiangmai. The acreage under durian appears to be expanding slowly, but rapidly in Thailand (in 1988 30% of Thai orchards were too young to bear fruit).

Properties

The arils represent 20-35 % of the fruit weight, the seeds 5-15%. The flesh and seed are very nutritious, being rich in carbohydrates, proteins, fats and minerals. The flesh contains per 100 g edible portion: water 67 g, protein 2.5 g, fat 2.5 g, carbohydrates 28.3 g, fibre 1.4 g, ash 0.8 g, calcium 20 mg, phosphorus 63 mg, potassium 601 mg, thiamine 0.27 mg, riboflavine 0.29 mg, and vitamin C 57 mg. The energy value is 520 kJ/100 g. The odour of the fruit stems largely from thiols or thioethers, esters and sulphides.

Description

Large, buttressed tree, growing in conformity with Roux's architectural model, up to 40 m tall; bark dark red-brown, peeling off irregularly, heartwood dark red. Leaves alternate, elliptical to lanceolate, 10-15(-17) cm x 3-4.5(-12.5) cm, chartaceous, base acute or obtuse, apex slenderly acuminate; upper surface glabrous, glossy, densely reticulate; lower surface densely covered with silvery or golden coloured scales with a layer of stellate hairs underneath. Inflorescences on older branches, forming fascicles of corymbs of 3-30 flowers, up to 15 cm long; pedicel 5-7 cm; flower buds globose-ovoid, 2 cm in diameter; epicalyx splitting into 2-3 ovate, concave, deciduous lobes of 1.5 cm length; flowers 5-6 cm long, about 2 cm in diameter, whitish or greenish-white, calyx tubular, 3 cm long with 5-6 triangular teeth; petals 5, spathulate, about twice as long as the calyx, at base narrowed into a conspicuous claw; stamens numerous, united in 5 free bundles; style pubescent, stigma capitellate. Fruit a globose, ovoid or ellipsoid capsule, up to 25 cm long and 20 cm diameter, green to brownish, covered with numerous broadly pyramidal, sharp, up to 1 cm long spines; valves usually 5, thick, fibrous. Seeds up to 4 cm long, completely covered by a white or yellowish, soft, very sweet aril.

Image

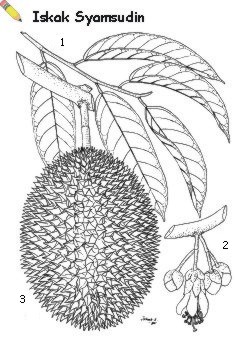

| Durio zibethinus Murray - 1, branchlet with leaves; 2, branch with flowers; 3, branch with fruit |

Growth and Development

Fresh seed germinates readily within 3-8 days, but viability declines rapidly in storage. The seedling grows fast with an orthotropic axis. Under favourable growing conditions numerous plagiotropic laterals are formed, emerging at a wide angle, as well as several more upright orthotropic laterals. The latter compete with the main axis, so that the prominent pyramidal shape of a thriving young tree eventually tends to get lost.

Shoot growth appears to be continuous, peaks in the rate of growth giving rise to 3-5 flushes per year. Soon the smallest laterals die back and this loss of branches continues throughout the tree's life; seedlings - particularly in close stands - eventually grow into sparingly branched tall trees with an irregular crown. Since durian is ramiflorous this implies a gradual loss of bearing wood. The juvenile phase often lasts 7-12 years and by the time flowering sets in, the trees have already attained an impressive size.

In Thailand durian flowers from March, after the end of the cool dry season. In monsoon climates flowering takes place late in the dry season; bloom in one year may be more than a month earlier or later than in another year. In the humid parts of Malaysia and Indonesia trees often flower twice a year, again with much variation in timing from one year to the next. These observations suggest that floral development may be associated with a period of subdued extension growth, e.g. following a cool or dry period. The favourable flowering response to low doses of growth retardants such as paclobutrazol, is in keeping with this view.

Whereas some floral initials emerge and reach anthesis without interruption in 6-8 weeks time, others emerge much earlier, up to 8 months prior to anthesis, but go through a period of apparent quiescence in the form of small clusters of round protuberances. When development is resumed, anthesis is reached within 6-8 weeks, along with the late floral initials. Sometimes the floral initials revert to vegetative growths. It is not clear how floral induction occurs, nor which factors determine the duration of the quiescent period and the reversion to vegetative expression. A tree flowers over a period of 2-3 weeks. The flowers open in the late afternoon; before midnight most pollen grains - and the calyx, petals and stamens - are shed. The stigma remains receptive until early morning and pollination is largely accomplished by nectarivorous bats and possibly by moths. The role played by wind pollination is not yet clear. Self-incompatibility is common; however, orchards planted with a single cultivar in Thailand show no signs of reduced fruit set. In the long tradition of cultivar selection in Thailand, compatibility may unwittingly have been an important selection criteria.

The fruit growth curve is sigmoid and in Thailand early cultivars are harvested 95-105 days after bloom, late cultivars after 130 days or more. In Peninsular Malaysia the fruit is most abundant between June and August. In several districts the season lasts longer and in other districts a second crop may be harvested in December or January. Sabah has virtually the same supply seasons, but in Sarawak durians are in the market between November and February.

Shoot growth appears to be continuous, peaks in the rate of growth giving rise to 3-5 flushes per year. Soon the smallest laterals die back and this loss of branches continues throughout the tree's life; seedlings - particularly in close stands - eventually grow into sparingly branched tall trees with an irregular crown. Since durian is ramiflorous this implies a gradual loss of bearing wood. The juvenile phase often lasts 7-12 years and by the time flowering sets in, the trees have already attained an impressive size.

In Thailand durian flowers from March, after the end of the cool dry season. In monsoon climates flowering takes place late in the dry season; bloom in one year may be more than a month earlier or later than in another year. In the humid parts of Malaysia and Indonesia trees often flower twice a year, again with much variation in timing from one year to the next. These observations suggest that floral development may be associated with a period of subdued extension growth, e.g. following a cool or dry period. The favourable flowering response to low doses of growth retardants such as paclobutrazol, is in keeping with this view.

Whereas some floral initials emerge and reach anthesis without interruption in 6-8 weeks time, others emerge much earlier, up to 8 months prior to anthesis, but go through a period of apparent quiescence in the form of small clusters of round protuberances. When development is resumed, anthesis is reached within 6-8 weeks, along with the late floral initials. Sometimes the floral initials revert to vegetative growths. It is not clear how floral induction occurs, nor which factors determine the duration of the quiescent period and the reversion to vegetative expression. A tree flowers over a period of 2-3 weeks. The flowers open in the late afternoon; before midnight most pollen grains - and the calyx, petals and stamens - are shed. The stigma remains receptive until early morning and pollination is largely accomplished by nectarivorous bats and possibly by moths. The role played by wind pollination is not yet clear. Self-incompatibility is common; however, orchards planted with a single cultivar in Thailand show no signs of reduced fruit set. In the long tradition of cultivar selection in Thailand, compatibility may unwittingly have been an important selection criteria.

The fruit growth curve is sigmoid and in Thailand early cultivars are harvested 95-105 days after bloom, late cultivars after 130 days or more. In Peninsular Malaysia the fruit is most abundant between June and August. In several districts the season lasts longer and in other districts a second crop may be harvested in December or January. Sabah has virtually the same supply seasons, but in Sarawak durians are in the market between November and February.

Other Botanical Information

Six species are mentioned in the chapter on minor edible fruits and nuts; the remaining species with edible fruit are primarily sources of timber, the fruit being of secondary importance. Many cultivars of Durio zibethinus exist. The major recommended ones are: Thailand: 'Kaan Yao', 'Mon Thong', 'Chanee', 'Kradum Thong', 'Luang' and 'Kob'; Malaysia: 'D2' (Dato Nina), 'D7', 'D10' (Durian Hijau), 'D24', 'D98' (Katoi), 'D99', 'D114' and 'D117' (Gombak); Indonesia: 'Sunan', 'Sukun', 'Hepe', 'Mas', 'Sitokong' and 'Petruk'.

Ecology

Durian is strictly tropical; it is grown successfully up to 800 m elevation near the equator, and up to 18° from the equator in Thailand and Queensland. At these extreme latitudes, extension growth comes to a halt during the coolest months (mean temperatures below 22°C), but flowering and fruiting appear to be more prolific than in the non-seasonal climates. A well-distributed rainfall of 1500 mm or more is needed, but relatively dry spells stimulate and synchronize flowering. If there is a prominent dry season, as in Chantaburi, the major durian production centre in Thailand, a dependable irrigation system is essential.

The soil should be deep, well-drained and light, rather than heavy, to limit tree losses from root rot. A sheltered site is desirable to prevent branches laden with fruit from breaking in gusty winds.

The soil should be deep, well-drained and light, rather than heavy, to limit tree losses from root rot. A sheltered site is desirable to prevent branches laden with fruit from breaking in gusty winds.

Propagation and planting

In Indonesia durian is still largely raised from seed, although several methods for clonal are practised. In the Philippines propagation from seed is being replaced by inarching and cleft grafting. In Thailand nurseries produce large numbers of trees in two ways. The traditional 'suckle graft' is a fairly simple and highly successful form of inarching, in which a bagged rootstock is decapitated and inserted into a small branch of the mother tree. The other method is hypocotyl-grafting, using potted, 5-6-week-old seedlings which are cleft-grafted with mini-scions cut from thin laterals of flushing shoots. Fungicide treatment, a polythene tunnel and heavy shade are needed to protect the tender tissues. Five skilled workers can set 3000 grafts, working from 8 p.m. to midnight(!); avoiding the heat of the day is said to be an important factor in achieving success rates above 90%. Seeds of cv. Chanee are used to raise rootstocks in Thailand.

The plants can be set out in the field after about one year, spaced 8-16 m apart. Shade is needed during the first year. At the closest spacing the orchard may need to be thinned after 8-10 years.

The plants can be set out in the field after about one year, spaced 8-16 m apart. Shade is needed during the first year. At the closest spacing the orchard may need to be thinned after 8-10 years.

Husbandry

Some standardization of techniques is being achieved in durian orchards in Thailand. In spite of the wide tree spacing intercropping is not common, but in older orchards durian was often interplanted with rambutan, or with mangosteen and langsat. The normal planting time is one month before the start of the rainy season, so that initially frequent watering is needed. Increasingly permanent irrigation systems are installed with PVC piping and often simple PVC sprinklers, 2 or 3 per tree, discharging their water near the drip line of the tree canopy. Weeds are slashed and remain as a mulch, but the area under the tree canopy is kept weed-free. Nutrient removal in the harvest amounts to 2.4 kg N, 0.4 kg P, 4.2 kg K, 0.3 kg Ca and 0.5 kg Mg per t fruit, but total nutrient flow has not yet been studied. The Thai practice is to work in a compound fertilizer near the drip line as soon as the flower buds emerge, supplemented by a top dressing if there is good fruit set; another fertilizer dressing follows after harvest. Where manure is available it may replace the last fertilizer application.

During the first years after planting the trees are shaped by removing orthotropic limbs, including watershoots, and by thinning out the plagiotropic laterals. Trees bear best on more or less horizontal limbs; upright limbs contribute more to tree size and height. In West Java trees are sometimes topped at a height of about 10 m to facilitate management.

Flowering and fruit set tend to be excessive in Thailand; when the flower buds measure 1 cm across they are thinned, the degree of thinning depending upon the cultivar. Fruitlets are thinned 4-6 weeks after bloom, leaving 1-2 fruit per panicle and limiting the number of fruit to 50-150 per tree. The upper limbs are allowed to bear only near the base, the lower limbs also in the more distal parts. The trunk should bear no fruit at all, as this reduces fruit size on the branches through competition. Hand pollination is sometimes practised in Thailand to improve fruit distribution over the tree and in particular to obtain fruits with well-developed arils in all 5 locules.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, the durian heartland, flowering and fruiting appear to be much more erratic; as a consequence, trees grow so large that thinning of flowers and fruits is hardly practicable. Apparently the environment does not impose a strict growth rhythm in which floral development has its secure place, and continuing vegetative growth may also compete with fruit set. If this reasoning is correct, it follows that husbandry should aim at emphasizing the weak seasonal fluctuations, stimulating extension growth during the main season(s) by careful timing of fertilizer dressings and curbing it through girdling or application of growth retardants in anticipation of the flowering season(s). In fact fertilizers may be counterproductive as long as the crop is too light to reduce tree growth noticeably; perhaps that is why few growers in Indonesia and Malaysia use them on durian. With regard to fruit set, other factors - e.g. inadequate (cross-)pollination - may also need to be considered. In Malaysia a cultivar mix of 60% 'D24', 30% 'D99' and 10% 'D98' or 'D10' is recommended to ensure adequate pollination and to extend the harvest period.

During the first years after planting the trees are shaped by removing orthotropic limbs, including watershoots, and by thinning out the plagiotropic laterals. Trees bear best on more or less horizontal limbs; upright limbs contribute more to tree size and height. In West Java trees are sometimes topped at a height of about 10 m to facilitate management.

Flowering and fruit set tend to be excessive in Thailand; when the flower buds measure 1 cm across they are thinned, the degree of thinning depending upon the cultivar. Fruitlets are thinned 4-6 weeks after bloom, leaving 1-2 fruit per panicle and limiting the number of fruit to 50-150 per tree. The upper limbs are allowed to bear only near the base, the lower limbs also in the more distal parts. The trunk should bear no fruit at all, as this reduces fruit size on the branches through competition. Hand pollination is sometimes practised in Thailand to improve fruit distribution over the tree and in particular to obtain fruits with well-developed arils in all 5 locules.

In Indonesia and Malaysia, the durian heartland, flowering and fruiting appear to be much more erratic; as a consequence, trees grow so large that thinning of flowers and fruits is hardly practicable. Apparently the environment does not impose a strict growth rhythm in which floral development has its secure place, and continuing vegetative growth may also compete with fruit set. If this reasoning is correct, it follows that husbandry should aim at emphasizing the weak seasonal fluctuations, stimulating extension growth during the main season(s) by careful timing of fertilizer dressings and curbing it through girdling or application of growth retardants in anticipation of the flowering season(s). In fact fertilizers may be counterproductive as long as the crop is too light to reduce tree growth noticeably; perhaps that is why few growers in Indonesia and Malaysia use them on durian. With regard to fruit set, other factors - e.g. inadequate (cross-)pollination - may also need to be considered. In Malaysia a cultivar mix of 60% 'D24', 30% 'D99' and 10% 'D98' or 'D10' is recommended to ensure adequate pollination and to extend the harvest period.

Diseases and Pests

Root rot, foot rot or patch canker, caused by Phytophthora palmivora, is a feared killer, particularly in orchards in Thailand. The fungus lives in the soil and weakens the tree by infecting the roots. Above-ground infections also occur, probably mainly through soil particles splashing up. Trees are killed when trunk infections eventually girdle the tree. To control the disease the trunk is kept free of laterals up to a height of 1 m or more, the area under the tree is kept weed-free and irrigation should not wet the trunk or the soil near it, nor should irrigation water be led from one tree basin to the next. A paste of (systemic) fungicide is painted on the trunk and the trees are frequently inspected, infections cut out and the wounds dressed.

In spite of all these measures the grower often fights a losing battle; susceptible cultivars such as 'Mon Thong' can hardly be adequately protected. Sustained mulching under the trees, which is proving so effective in controlling root rot in avocado, deserves thorough testing in durian, the more so since opinion is divided: growers generally fear that mulching will aggravate patch canker, supposedly because it keeps the topsoil moist or because the orchard remains humid for too long following rain.

Durio lowianus Scort. & King and in particular Durio mansoni (Gamble) Bakh. have resistance against Phytophora palmivora, also when used as durian rootstocks. Moreover Durio mansoni may have a dwarfing effect, as the stock does not thicken at the same rate as the scion. Unfortunately, trials with these stocks in Thailand have been discontinued because of the low percentage take of the grafts and because the scion overgrowth was considered a sign of incompatibility.

Other diseases - including leaf spots caused by a Colletotrichum spp., Homostegia durionis and Phyllosticta durionis and fruit rot (Rhizopus sp.) - are of limited importance. Numerous pests have been observed on durian, but the damage appears to be rather incidental. A fruit boring caterpillar, Hypoperigea (Plagideicta) leprostricta, eats the seeds and apparently occurs more frequently. Mammals - including rats, swine and bears - are keen on the fruit and fallen fruit has to be gathered every morning to limit losses.

In spite of all these measures the grower often fights a losing battle; susceptible cultivars such as 'Mon Thong' can hardly be adequately protected. Sustained mulching under the trees, which is proving so effective in controlling root rot in avocado, deserves thorough testing in durian, the more so since opinion is divided: growers generally fear that mulching will aggravate patch canker, supposedly because it keeps the topsoil moist or because the orchard remains humid for too long following rain.

Durio lowianus Scort. & King and in particular Durio mansoni (Gamble) Bakh. have resistance against Phytophora palmivora, also when used as durian rootstocks. Moreover Durio mansoni may have a dwarfing effect, as the stock does not thicken at the same rate as the scion. Unfortunately, trials with these stocks in Thailand have been discontinued because of the low percentage take of the grafts and because the scion overgrowth was considered a sign of incompatibility.

Other diseases - including leaf spots caused by a Colletotrichum spp., Homostegia durionis and Phyllosticta durionis and fruit rot (Rhizopus sp.) - are of limited importance. Numerous pests have been observed on durian, but the damage appears to be rather incidental. A fruit boring caterpillar, Hypoperigea (Plagideicta) leprostricta, eats the seeds and apparently occurs more frequently. Mammals - including rats, swine and bears - are keen on the fruit and fallen fruit has to be gathered every morning to limit losses.

Harvesting

The trees grow very tall and as it is difficult to judge maturity, it is common practice to wait until the fruit drops. In Thailand regular heavy crops greatly reduce tree vigour and picking is feasible. Selective harvesting is necessary and skilled pickers use a range of criteria to judge maturity. Starting with the number of days lapsed since full bloom, they may also consider: colour, elasticity and disposition of the spines, the intensity of the odour emitted by the fruit, the sound heard when the fingertips are run through the furrows between the spines, changes in the fruit stalk, and flotation tests in water.

Yield

In most of South-East Asia yields appear to be low and erratic, mainly as a result of poor flowering and inadequate fruit set. In Thailand these constraints are much less serious, but mean yields calculated from statistics on area and production in successive years are nevertheless low, ranging from 3.1 to 8.3 t/ha per year. Good orchards in Thailand and Perak, the durian centre in Malaysia, produce 10-18 t/ha per year, which is about 50 fruits per tree of 1.5-4 kg each.

Handling After Harvest

The strong rind facilitates transport of the fruit, but the spines make handling difficult; the fruit has to be held by the stalk. Fruit which split open upon hitting the ground deteriorate quickly, the aril going rancid in 36 hours. Fruit gathered intact under the tree remain edible for 2-3 days, but shelf life of picked fruit extends to about one week, which is a great advantage.

The fruit is taken to market without delay, carried in bags, bamboo baskets or in bulk on a truck. Cold storage at 15 °C can extend shelf life to about 3 weeks and quick-frozen arils retain their flavour for 3 months or more.

The fruit is taken to market without delay, carried in bags, bamboo baskets or in bulk on a truck. Cold storage at 15 °C can extend shelf life to about 3 weeks and quick-frozen arils retain their flavour for 3 months or more.

Genetic Resources

All countries in South-East Asia hold germplasm collections of durians, and so do Australia (Darwin, Cairns) and Florida. These collections need to be further supplemented, also with related species. The latter have potential, either as edible fruits in their own right, or as rootstocks or breeding parents for durian.

Breeding

Durian progeny are very heterozygous in all attributes, and because of propagation by seed most traditional cultivars in Indonesia and Malaysia are ill-defined. In Malaysia a formal selection programme in this material has resulted in a series of clones, denoted D1, D2, etc. In Thailand the tradition of clonal propagation has given rise to numerous cultivars, of which only a few are grown widely in commercial orchards.

Within the genus, hybridization appears to be relatively easy. Most wild species can contribute genes for disease resistance (e.g. Phytophthora palmivora). Durio acutifolius (Masters) Kosterm. and Durio griffithii (Masters) Bakh. flower more reliably. Durio wyatt-smithii Kosterm. deserves consideration by breeders since it may be the wild ancestor of the cultivated durian. It has a shorter calyx and longer, more slender spines on the fruit.

Within the genus, hybridization appears to be relatively easy. Most wild species can contribute genes for disease resistance (e.g. Phytophthora palmivora). Durio acutifolius (Masters) Kosterm. and Durio griffithii (Masters) Bakh. flower more reliably. Durio wyatt-smithii Kosterm. deserves consideration by breeders since it may be the wild ancestor of the cultivated durian. It has a shorter calyx and longer, more slender spines on the fruit.

Prospects

Durian has a special appeal to most South-East Asians, but relatively low productivity keeps up the price and limits consumption. The main challenge is to find ways to raise the yield level through manipulation of the growth rhythm. If successful, this approach may make it possible to extend the harvest season, which would further enhance the role of this unique fruit in South-East Asia.

In the absence of a breakthrough in productivity in the countries of origin, Thailand and other 'fringe' countries with better yields will have the edge in the international trade. Thailand already has a significant export trade both of fresh fruit (80% of exports) and of deep-frozen arils. There appear to be excellent for expansion of this trade, also with countries outside Asia, even though for people who have not grown up with the fruit it represents a taste that is not easily acquired.

In the absence of a breakthrough in productivity in the countries of origin, Thailand and other 'fringe' countries with better yields will have the edge in the international trade. Thailand already has a significant export trade both of fresh fruit (80% of exports) and of deep-frozen arils. There appear to be excellent for expansion of this trade, also with countries outside Asia, even though for people who have not grown up with the fruit it represents a taste that is not easily acquired.

Literature

Burate Bamrungkarn, L., 1971. Durian plantation. Prae Pittaya Publishers, Bangkok (in Thai).

Corner, E.J.H., 1949. The durian theory of the origin of the modern tree. Annals of Botany 13(52): 367-414.

Hasan, B.M. & Yaacob, O., 1986. The growth and productivity of selected durian clones under the plantation system at Serdang, Malaysia. Acta Horticulturae 175: 55-58.

Kostermans, A.J.G.H., 1958. The genus Durio Adans. (Bombac.). Reinwardtia 4(3): 357-460.

Punsri, P., 1970. Observations on durian plantation. Puech Suan 6(4): 49-59 (in Thai).

Punsri, P., 1972. Wild durian. Puech Suan 8(2): 17-22 (in Thai).

Soegeng-Reksodihardjo, W., 1962. The species of Durio with edible fruits. Economic Botany 16: 270-282.

Soepadmo, E. & Eow, B.K., 1976. The reproductive biology of Durio zibethinus Murr. The Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 29: 25-33.

Valmayor, R.V., Coronel, R.E. & Ramirez, D.A., 1965. Studies of floral biology, fruit set and development in durian. The Philippine Agriculturists 48: 355-359.

Corner, E.J.H., 1949. The durian theory of the origin of the modern tree. Annals of Botany 13(52): 367-414.

Hasan, B.M. & Yaacob, O., 1986. The growth and productivity of selected durian clones under the plantation system at Serdang, Malaysia. Acta Horticulturae 175: 55-58.

Kostermans, A.J.G.H., 1958. The genus Durio Adans. (Bombac.). Reinwardtia 4(3): 357-460.

Punsri, P., 1970. Observations on durian plantation. Puech Suan 6(4): 49-59 (in Thai).

Punsri, P., 1972. Wild durian. Puech Suan 8(2): 17-22 (in Thai).

Soegeng-Reksodihardjo, W., 1962. The species of Durio with edible fruits. Economic Botany 16: 270-282.

Soepadmo, E. & Eow, B.K., 1976. The reproductive biology of Durio zibethinus Murr. The Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 29: 25-33.

Valmayor, R.V., Coronel, R.E. & Ramirez, D.A., 1965. Studies of floral biology, fruit set and development in durian. The Philippine Agriculturists 48: 355-359.

Author(s)

Suranant Subhadrabandhu, J.M.P. Schneemann & E.W.M. Verheij

Correct Citation of this Article

Subhadrabandhu, S., Schneemann, J.M.P. & Verheij, E.W.M., 1991. Durio zibethinus Murray. In: Verheij, E.W.M. and Coronel, R.E. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 2: Edible fruits and nuts. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.