Record Number

6036

PROSEA Handbook Number

5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers

Taxon

Parkia R. Br.

Protologue

Denham & Clapp., Narr. Travels Africa, Bot. App.: 289 (1826).

Family

LEGUMINOSAE

Chromosome Numbers

x = 12, 13; P. speciosa: 2n = 24, 26

Vernacular Names

Petai (trade name). Thailand: sato.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Parkia is a pantropical genus with about 35 species, most of them being found in tropical America, especially in the Amazon basin. In Asia Parkia occurs from north-eastern India and Bangladesh east through Burma (Myanmar), Indo-China and Thailand to the whole of the Malesian region, with more isolated species in Micronesia and Fiji. About 5 species occur within Malesia. Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra and Borneo are richest, each with 4 species. P. timoriana has the largest area of distribution, occurring from India to New Guinea.

Uses

The wood of Parkia is used locally for temporary light construction, carpentry, furniture and cabinet making, moulding, interior finish, cladding, concrete shuttering, boxes, crates, matches, clogs, disposable chopsticks, fish-net floats and paper. General utility purpose plywood has been manufactured from the wood. In Peninsular Malaysia P. singularis wood is a popular firewood.

This species is sometimes used as a shade tree, e.g. for coffee plantations and in nurseries. The seeds are commonly used as a vegetable; they have a garlic flavour. Young leaves and the receptacle of the inflorescence are occasionally eaten. The seeds are used in local medicine against hepatalgia, oedema, nephritis, colic, cholera, diabetes and as anthelmintic, and also applied externally to wounds and ulcers. Powdered bark of P. sumatrana has been reported to be used against leeches in Indo-China, and the bark of P. timoriana against scabies, boils and abscesses.

This species is sometimes used as a shade tree, e.g. for coffee plantations and in nurseries. The seeds are commonly used as a vegetable; they have a garlic flavour. Young leaves and the receptacle of the inflorescence are occasionally eaten. The seeds are used in local medicine against hepatalgia, oedema, nephritis, colic, cholera, diabetes and as anthelmintic, and also applied externally to wounds and ulcers. Powdered bark of P. sumatrana has been reported to be used against leeches in Indo-China, and the bark of P. timoriana against scabies, boils and abscesses.

Production and International Trade

Parkia timber generally does not reach the market because it is considered of poor quality and supplies are limited.

Properties

Parkia yields a usually lightweight, occasionally medium-weight hardwood with a density of 350-810 kg/m3 at 15% moisture content. Heartwood white, yellow-white or pale yellowish-brown, in older trees with paler and darker streaks, not clearly differentiated from the rather wide paler coloured sapwood (25 cm wide sapwood once recorded for P. timoriana), very occasionally darker coloured core present; grain straight or slightly interlocked; texture moderately coarse and uneven; wood with unpleasant garlic or bean-like odour when fresh. Growth rings indistinct or visible due to colour differences, narrow layers of marginal parenchyma only visible with a hand lens; vessels medium-sized to very large, mostly solitary, also in radial multiples of 2-3, sometimes more than 4, occasionally with red gum-like deposits; parenchyma abundant, paratracheal aliform and confluent, and apotracheal in marginal or seemingly marginal bands and diffuse, the latter type rare; rays very fine to medium-sized, visible to the naked eye; ripple marks absent, but rays irregularly storied; occasionally with pith flecks.

Shrinkage upon seasoning is low; degrade during seasoning is mainly due to insect attack and blue stain, whereas end-checks have been observed in P. speciosa. It takes respectively 3-4 months and 4.5-5 months to air dry boards 13 mm and 38 mm thick. The wood is soft to moderately hard in P. singularis and weak. The wood is relatively easy to work, saw and machine, both when green and when air-dry; it can be planed well and gives a smooth finish, but boring and turning give a rough finish. The production of rotary veneer is satisfactory, but the production of good-quality plywood is doubtful. The wood is non-durable with a service life of about one year for P. speciosa wood, but preservative treatment applying the standard open-tank method with creosote is very easy, and an absorption of 320 kg/m3 has been obtained in P. speciosa. A dry salt retention of 12.3 kg/m3 of copper-chrome-arsenic solution was obtained in treating P. speciosa wood by the vacuum-pressure method. The wood is not resistant to any kind of insect or wood-borer attack nor to wood-staining fungi. The sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus.

See also the tables on microscopic wood anatomy and wood properties.

Shrinkage upon seasoning is low; degrade during seasoning is mainly due to insect attack and blue stain, whereas end-checks have been observed in P. speciosa. It takes respectively 3-4 months and 4.5-5 months to air dry boards 13 mm and 38 mm thick. The wood is soft to moderately hard in P. singularis and weak. The wood is relatively easy to work, saw and machine, both when green and when air-dry; it can be planed well and gives a smooth finish, but boring and turning give a rough finish. The production of rotary veneer is satisfactory, but the production of good-quality plywood is doubtful. The wood is non-durable with a service life of about one year for P. speciosa wood, but preservative treatment applying the standard open-tank method with creosote is very easy, and an absorption of 320 kg/m3 has been obtained in P. speciosa. A dry salt retention of 12.3 kg/m3 of copper-chrome-arsenic solution was obtained in treating P. speciosa wood by the vacuum-pressure method. The wood is not resistant to any kind of insect or wood-borer attack nor to wood-staining fungi. The sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus.

See also the tables on microscopic wood anatomy and wood properties.

Botany

Deciduous, medium-sized to large trees up to 50 m tall; bole up to 100(-250) cm in diameter, buttresses small to large (up to 4 m high and spreading up to 2 m) or absent; bark surface smooth to rough, fissured or flaky, pale greyish to reddish-brown, inner bark fibrous, hard, usually pinkish or reddish to deep red-brown, sometimes streaked or mottled, with a strong smell of beans. Leaves alternate or opposite, bipinnate with up to 30(-42) pairs of pinnae; leaflets opposite, sessile; petiole and rachis usually with extrafloral nectaries; stipules small, caducous. Flowers in a long-stalked, pendulous, pyriform to clavate, dense head, sterile flowers at base of inflorescence, male ones in middle portion and bisexual ones at apex, 5-merous; calyx long-tubular or funnel-shaped with imbricate lobes; corolla longer than calyx; stamens 10, connate below, shortly exserted; ovary superior, short-stiped, style exserted. Fruit a leathery or woody, stalked, linear to strap-shaped or oblong pod, usually indehiscent, many-seeded, usually several pods together in a pendent infructescence with swollen receptacle. Seeds in 1 row, ellipsoid, with a pleurogram. Seedling with epigeal germination; cotyledons fleshy, peltate; epicotyl with a scale leaf and subsequently bipinnate leaves.

P. speciosa and P. timoriana show a synchronized annual cycle of flowering, fruiting and leaf fall; the trees are without leaves for 2-3 weeks each year. They start flowering when 10-15 m tall, but vegetatively propagated P. speciosa starts flowering and fruiting a few years after planting. The flowering heads are usually pollinated by bats, but are also visited by insects and birds. They produce a foetid odour and a copious nocturnal supply of nectar. Hornbills, monkeys, squirrels, deer, elephants and wild pigs feed on the fruits and probably disperse the seeds. In Java P. timoriana flowers in April-July and usually many fruits are found in June-August. A 24-year-old P. timoriana tree in the arboretum of the Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong had attained only 13.8 m in height and 9.2 cm in diameter.

Parkia is classified in the tribe Parkieae of the subfamily Mimosoideae, together with Pentaclethra, which is confined to tropical Africa and America.

P. timoriana is often cited as P. javanica (Lamk) Merr., especially in Malaysian literature. Although the latter name is older and would therefore have priority, it has been superseded because the correct identity of the species concerned cannot be recovered. The status of P. intermedia Hassk. is uncertain, but it is probably a hybrid between P. speciosa and P. timoriana; it is found almost exclusively in Java. P. sherfeseei Merr. from the Philippines (Mindanao) is possibly conspecific with P. sumatrana.

P. speciosa and P. timoriana show a synchronized annual cycle of flowering, fruiting and leaf fall; the trees are without leaves for 2-3 weeks each year. They start flowering when 10-15 m tall, but vegetatively propagated P. speciosa starts flowering and fruiting a few years after planting. The flowering heads are usually pollinated by bats, but are also visited by insects and birds. They produce a foetid odour and a copious nocturnal supply of nectar. Hornbills, monkeys, squirrels, deer, elephants and wild pigs feed on the fruits and probably disperse the seeds. In Java P. timoriana flowers in April-July and usually many fruits are found in June-August. A 24-year-old P. timoriana tree in the arboretum of the Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong had attained only 13.8 m in height and 9.2 cm in diameter.

Parkia is classified in the tribe Parkieae of the subfamily Mimosoideae, together with Pentaclethra, which is confined to tropical Africa and America.

P. timoriana is often cited as P. javanica (Lamk) Merr., especially in Malaysian literature. Although the latter name is older and would therefore have priority, it has been superseded because the correct identity of the species concerned cannot be recovered. The status of P. intermedia Hassk. is uncertain, but it is probably a hybrid between P. speciosa and P. timoriana; it is found almost exclusively in Java. P. sherfeseei Merr. from the Philippines (Mindanao) is possibly conspecific with P. sumatrana.

Image

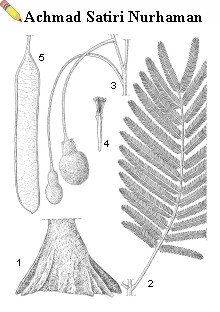

| Parkia timoriana (DC.) Merr. – 1, base of trunk; 2, leaf; 3, flowering heads; 4, flower; 5, fruit. |

Ecology

Parkia occurs scattered in lowland rain forest and sometimes also in tall secondary forest, on sandy, loamy and podzolic soils, also in waterlogged locations, in freshwater swamp forest and on river banks, up to 1000(-1400) m altitude. P. sumatrana and P. timoriana also occur in dry evergreen forest, often along streams.

Silviculture and Management

Parkia can be propagated by seed and by vegetative means. Seeds of P. timoriana can be hand-picked from underneath mother trees from the hard, indehiscent pods that should be opened with a chopping knife. P. timoriana has 1000-1400 dry seeds/kg. Seedlings of P. speciosa are collected by farmers from the wild and planted in their home garden or fields. About 90% of the soft seeds of P. speciosa germinate in 3-15 days; the germination rate of the hard seeds of P. timoriana is about 55% in 8-103 days. Mechanical scarification is recommended for the latter. In a test in Thailand, 3-year-old seed had a germination rate of only 8.5% whereas nicked seed had a germination rate of 90.5% in only 4-8 days. A pretreatment with concentrated sulphuric acid for 15 minutes gave a germination of 95%. P. speciosa can be propagated by stem cuttings and budding, but P. timoriana cannot be propagated vegetatively. Seedlings of P. timoriana can be stumped with 10-20 cm shoot and 20-40 cm root length, and survival after planting is 100%. In Java growth during the first 5 years was fast, but then slowed down. For optimal growth ample space and light are necessary. Mixed plantations with Lagerstroemia speciosa (L.) Pers. and Artocarpus heterophyllus Lamk planted in alternating rows at 3 m x 1 m spacing were successful with a production of 65 m3/ha clear bole volume at the age of 15.5 years. The mean diameter of P. timoriana at this age is 15.6-20.4 cm and its height is 14.5-16.1 m. Some unidentified borers have been found tunnelling in the stem of living trees. In Malaysia it is recommended to treat timber of Parkia with anti-stain chemicals immediately after sawing. In a survey of almost 700 ha of primary forest in Peninsular Malaysia, an average of 0.22 trees/ha of P. singularis and P. speciosa with a diameter of over 40 cm was found, but usually these species are much less common.

Genetic Resources and Breeding

Within Malesia no seed or germplasm collections of Parkia are known to exist and no breeding programmes are being carried out. Most species have a fairly wide area of distribution and are also cultivated, suggesting that it is unlikely that they are threatened. P. versteeghii, however, seems to be rare.

Prospects

There is little scope for increased utilization of the timber of Parkia as it is non-durable and of poor quality. Only the quality and durability of the timber of P. singularis is slightly better, but its scattered occurrence makes exploitation difficult.

Literature

[16]Ahmad Shakri Mat Seman, 1984. Malaysian timbers - petai. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 85. Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 7 pp.

[70]Backer, C.A. & Bakhuizen van den Brink Jr., R.C., 1963-1968. Flora of Java. 3 volumes. Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[162]Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Sabah Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Sabah, Sandakan. xviii + 501 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[198]Cockburn, P.F., 1976-1980. Trees of Sabah. 2 volumes. Sabah Forest Records No 10. Forest Department Sabah, Sandakan.

[209]Corner, E.J.H., 1988. Wayside trees of Malaya. 3rd edition. 2 volumes. The Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur. 774 pp.

[235]de Guzman, E.D., Umali, R.M. & Sotalbo, E.D., 1986. Guide to the Philippine flora and fauna. Vol. 3: Dipterocarps, non-dipterocarps. Natural Resources Management Centre, Ministry of Natural Resources, Quezon City & University of the Philippines, Los Baños. xx + 414 pp.

[260]den Berger, L.G., 1926. Houtsoorten der cultuurgebieden van Java en Sumatra's oostkust [Tree species of the cultivated areas of Java and the east coast of Sumatra]. Mededeelingen No 13. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[302]Eddowes, P.J., 1980. Lesser known timber species of SEALPA countries. A review and summary. South East Asia Lumber Producers' Association, Jakarta. 132 pp.

[304]Eddowes, P.J., 1995-1997. The forests and timbers of Papua New Guinea. (unpublished data).

[316]Engku Abdul Rahman, 1980. Basic and grade stresses for some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 38 (reprinted). Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 13 pp.

[341]Flora Malesiana (various editors), 1950-. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Boston, London.

[343]Flore du Cambodge, du Laos et du Viêtnam (various editors), 1960-. Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris.

[348]Forest Products Research Centre, 1967. Properties and uses of Papua and New Guinea timbers. Forest Products Research Centre, Port Moresby. 30 pp.

[387]Grewal, G.S., 1979. Air-seasoning properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 41. Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 26 pp.

[405]Hardjowasono, M.S., 1942. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of various fruits and seeds]. Korte Mededelingen No 20. Bosbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 172 pp.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[448]Hopkins, H.C.F., 1994. The Indo-Pacific species of Parkia (Leguminosae: Mimosoideae). Kew Bulletin 49: 181-234.

[464]Ilic, J., 1990. The CSIRO macro key for hardwood identification. CSIRO, Highett. 125 pp.

[488]Japing, H.W. & Oey Djoen Seng, 1936. Cultuurproeven met wildhoutsoorten in Gadoengan - met overzicht van de literatuur betreffende deze soorten [Trial plantations of non teak wood species in Gadungan (East Java) - with survey of literature about these species]. Korte Mededeelingen No 55, part I to VI. Boschbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 270 pp.

[577]Kobmoo, B., Chaichanasuwat, O. & Pukittiyacamee, P., 1990. A preliminary study on the pretreatment of seed of leguminous species. The Embryon 3(1): 6-10.

[632]Kraemer, J.H., 1951. Trees of the western Pacific region. Tri-State Offset Company, Cincinnatti. 436 pp.

[633]Kramer, F., 1925. Kultuurproeven met industrie-, konstruktie- en luxe-houtsoorten [Investigations regarding the cultivation of different Javanese trees]. Mededeelingen No 12. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 99 pp.

[677]Lee, Y.H. & Chu, Y.P., 1965. The strength properties of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forester 28: 307-319.

[678]Lee, Y.H., Engku Abdul Rahman bin Chik & Chu, Y.P., 1979. The strength properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 34 (revised edition). Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 107 pp.

[679]Lee, Y.H. & Lopez, D.T., 1980. The machining properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 35 (revised edition). Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 31 pp.

[740]Malaysian Timber Industry Board, 1984. Peraturan pemeringkatan kayu keras gergaji Malaysia [The Malaysian grading rules for sawn hardwood timber]. Ministry of Primary Industries, Kuala Lumpur. 109 pp.

[741]Malaysian Timber Industry Board, 1986. 100 Malaysian timbers. Kuala Lumpur. x + 226 pp.

[770]Medway, Lord, 1972. Phenology of a tropical rain forest in Malaya. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 4(2): 117-146.

[780]Meniado, J.A. et al., 1975-1981. Wood identification handbook for Philippine timbers. 2 volumes. Government Printing Office, Manila. 370 pp. & 186 pp.

[825]Ng, F.S.P., 1978. Strategies of establishment in Malayan forest trees. In: Tomlinson, P.B. & Zimmermann, M.H. (Editors): Tropical trees as living systems. The proceedings of the fourth Cabot symposium held at Harvard Forest, Petersham, Massachusetts on April 26-30, 1976. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, London, New York, Melbourne. pp. 129-162.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[832]Ng, F.S.P. & Tang, H.T., 1974. Comparative growth rates of Malaysian trees. Malaysian Forester 37: 2-23.

[862]Oey Djoen Seng, 1964. Berat djenis dari djenis-djenis kaju Indonesia dan pengartian beratnja kaju untuk keperluan praktek [Specific gravity of Indonesian woods and its significance for practical use]. Pengumuman No 1. Lembaga Penelitian Hasil Hutan, Bogor. 233 pp.

[882]Perry, L.M., 1980. Medicinal plants of East and Southeast Asia. Attributed properties and uses. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 620 pp.

[933]Research Institute of Wood Industry, 1988. Identification, properties and uses of some Southeast Asian woods. Chinese Academy of Forestry, Wan Shou Shan, Beijing & International Tropical Timber Organization, Yokohama. 201 pp.

[934]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[955]Rocafort, J.E., Floresca, A.R. & Siopongco, J.O., 1971. Fourth progress report on the specific gravity of Philippine woods. Philippine Architecture, Engineering & Construction Report 18(5): 17-27.

[972]Sahri, M.M., Harun, J. & Hung, L.K., 1989. Treatability study of four under-utilized species of Malaysian hardwoods using the pressure treatment method. IAWA Bulletin n.s. 10: 345-346.

[980]Sasaki, S. 1980. Storage and germination of some Malaysian legume seeds. Malaysian Forester 43: 161-165.

[987]Saw, L.G., LaFrankie, J.V., Kochummen, K.M. & Yap, S.K., 1991. Fruit trees in a Malaysian rain forest. Economic Botany 45: 120-136.

[1015]Siemonsma, J.S. & Kasem Piluek (Editors), 1993. Plant resources of South-East Asia No 8. Vegetables. Pudoc Scientific Publishers, Wageningen. 412 pp.

[1039]Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Editors), 1970-. Flora of Thailand. The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok.

[1053]Start, A.N. & Marshall, A.G., 1976. Nectarivorous bats as pollinators of trees in West Malaysia. In: Burley, J. & Styles, B.T. (Editors): Tropical trees. Variation, breeding and conservation. Linnean Society Symposium Series No 2. Academic Press, London. pp. 141-150.

[1163]Verdcourt, B., 1979. A manual of New Guinea legumes. Botany Bulletin No 11. Office of Forests, Division of Botany, Lae. 645 pp.

[1198]Weidelt, H.J. (Editor), 1976. Manual of reforestation and erosion control for the Philippines. Schriftenreihe No 22. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Eschborn. 569 pp.

[1218]Whitmore, T.C., 1984. Tropical rainforest of the Far East. 2nd edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford. xvi + 352 pp.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1226]Willan, R.L., 1985. A guide to forest seed handling with special reference to the tropics. FAO Forestry Paper 20/2. FAO, Rome. 379 pp.

[70]Backer, C.A. & Bakhuizen van den Brink Jr., R.C., 1963-1968. Flora of Java. 3 volumes. Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[162]Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Sabah Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Sabah, Sandakan. xviii + 501 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[198]Cockburn, P.F., 1976-1980. Trees of Sabah. 2 volumes. Sabah Forest Records No 10. Forest Department Sabah, Sandakan.

[209]Corner, E.J.H., 1988. Wayside trees of Malaya. 3rd edition. 2 volumes. The Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur. 774 pp.

[235]de Guzman, E.D., Umali, R.M. & Sotalbo, E.D., 1986. Guide to the Philippine flora and fauna. Vol. 3: Dipterocarps, non-dipterocarps. Natural Resources Management Centre, Ministry of Natural Resources, Quezon City & University of the Philippines, Los Baños. xx + 414 pp.

[260]den Berger, L.G., 1926. Houtsoorten der cultuurgebieden van Java en Sumatra's oostkust [Tree species of the cultivated areas of Java and the east coast of Sumatra]. Mededeelingen No 13. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[302]Eddowes, P.J., 1980. Lesser known timber species of SEALPA countries. A review and summary. South East Asia Lumber Producers' Association, Jakarta. 132 pp.

[304]Eddowes, P.J., 1995-1997. The forests and timbers of Papua New Guinea. (unpublished data).

[316]Engku Abdul Rahman, 1980. Basic and grade stresses for some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 38 (reprinted). Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 13 pp.

[341]Flora Malesiana (various editors), 1950-. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Boston, London.

[343]Flore du Cambodge, du Laos et du Viêtnam (various editors), 1960-. Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris.

[348]Forest Products Research Centre, 1967. Properties and uses of Papua and New Guinea timbers. Forest Products Research Centre, Port Moresby. 30 pp.

[387]Grewal, G.S., 1979. Air-seasoning properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 41. Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 26 pp.

[405]Hardjowasono, M.S., 1942. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of various fruits and seeds]. Korte Mededelingen No 20. Bosbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 172 pp.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[448]Hopkins, H.C.F., 1994. The Indo-Pacific species of Parkia (Leguminosae: Mimosoideae). Kew Bulletin 49: 181-234.

[464]Ilic, J., 1990. The CSIRO macro key for hardwood identification. CSIRO, Highett. 125 pp.

[488]Japing, H.W. & Oey Djoen Seng, 1936. Cultuurproeven met wildhoutsoorten in Gadoengan - met overzicht van de literatuur betreffende deze soorten [Trial plantations of non teak wood species in Gadungan (East Java) - with survey of literature about these species]. Korte Mededeelingen No 55, part I to VI. Boschbouwproefstation, Buitenzorg. 270 pp.

[577]Kobmoo, B., Chaichanasuwat, O. & Pukittiyacamee, P., 1990. A preliminary study on the pretreatment of seed of leguminous species. The Embryon 3(1): 6-10.

[632]Kraemer, J.H., 1951. Trees of the western Pacific region. Tri-State Offset Company, Cincinnatti. 436 pp.

[633]Kramer, F., 1925. Kultuurproeven met industrie-, konstruktie- en luxe-houtsoorten [Investigations regarding the cultivation of different Javanese trees]. Mededeelingen No 12. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 99 pp.

[677]Lee, Y.H. & Chu, Y.P., 1965. The strength properties of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forester 28: 307-319.

[678]Lee, Y.H., Engku Abdul Rahman bin Chik & Chu, Y.P., 1979. The strength properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 34 (revised edition). Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 107 pp.

[679]Lee, Y.H. & Lopez, D.T., 1980. The machining properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 35 (revised edition). Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 31 pp.

[740]Malaysian Timber Industry Board, 1984. Peraturan pemeringkatan kayu keras gergaji Malaysia [The Malaysian grading rules for sawn hardwood timber]. Ministry of Primary Industries, Kuala Lumpur. 109 pp.

[741]Malaysian Timber Industry Board, 1986. 100 Malaysian timbers. Kuala Lumpur. x + 226 pp.

[770]Medway, Lord, 1972. Phenology of a tropical rain forest in Malaya. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 4(2): 117-146.

[780]Meniado, J.A. et al., 1975-1981. Wood identification handbook for Philippine timbers. 2 volumes. Government Printing Office, Manila. 370 pp. & 186 pp.

[825]Ng, F.S.P., 1978. Strategies of establishment in Malayan forest trees. In: Tomlinson, P.B. & Zimmermann, M.H. (Editors): Tropical trees as living systems. The proceedings of the fourth Cabot symposium held at Harvard Forest, Petersham, Massachusetts on April 26-30, 1976. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, London, New York, Melbourne. pp. 129-162.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[832]Ng, F.S.P. & Tang, H.T., 1974. Comparative growth rates of Malaysian trees. Malaysian Forester 37: 2-23.

[862]Oey Djoen Seng, 1964. Berat djenis dari djenis-djenis kaju Indonesia dan pengartian beratnja kaju untuk keperluan praktek [Specific gravity of Indonesian woods and its significance for practical use]. Pengumuman No 1. Lembaga Penelitian Hasil Hutan, Bogor. 233 pp.

[882]Perry, L.M., 1980. Medicinal plants of East and Southeast Asia. Attributed properties and uses. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 620 pp.

[933]Research Institute of Wood Industry, 1988. Identification, properties and uses of some Southeast Asian woods. Chinese Academy of Forestry, Wan Shou Shan, Beijing & International Tropical Timber Organization, Yokohama. 201 pp.

[934]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[955]Rocafort, J.E., Floresca, A.R. & Siopongco, J.O., 1971. Fourth progress report on the specific gravity of Philippine woods. Philippine Architecture, Engineering & Construction Report 18(5): 17-27.

[972]Sahri, M.M., Harun, J. & Hung, L.K., 1989. Treatability study of four under-utilized species of Malaysian hardwoods using the pressure treatment method. IAWA Bulletin n.s. 10: 345-346.

[980]Sasaki, S. 1980. Storage and germination of some Malaysian legume seeds. Malaysian Forester 43: 161-165.

[987]Saw, L.G., LaFrankie, J.V., Kochummen, K.M. & Yap, S.K., 1991. Fruit trees in a Malaysian rain forest. Economic Botany 45: 120-136.

[1015]Siemonsma, J.S. & Kasem Piluek (Editors), 1993. Plant resources of South-East Asia No 8. Vegetables. Pudoc Scientific Publishers, Wageningen. 412 pp.

[1039]Smitinand, T. & Larsen, K. (Editors), 1970-. Flora of Thailand. The Forest Herbarium, Royal Forest Department, Bangkok.

[1053]Start, A.N. & Marshall, A.G., 1976. Nectarivorous bats as pollinators of trees in West Malaysia. In: Burley, J. & Styles, B.T. (Editors): Tropical trees. Variation, breeding and conservation. Linnean Society Symposium Series No 2. Academic Press, London. pp. 141-150.

[1163]Verdcourt, B., 1979. A manual of New Guinea legumes. Botany Bulletin No 11. Office of Forests, Division of Botany, Lae. 645 pp.

[1198]Weidelt, H.J. (Editor), 1976. Manual of reforestation and erosion control for the Philippines. Schriftenreihe No 22. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH, Eschborn. 569 pp.

[1218]Whitmore, T.C., 1984. Tropical rainforest of the Far East. 2nd edition. Clarendon Press, Oxford. xvi + 352 pp.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1226]Willan, R.L., 1985. A guide to forest seed handling with special reference to the tropics. FAO Forestry Paper 20/2. FAO, Rome. 379 pp.

Author(s)

F.M. Setyowati

Parkia singularis

Parkia speciosa

Parkia sumatrana

Parkia timoriana

Parkia versteeghii

Parkia speciosa

Parkia sumatrana

Parkia timoriana

Parkia versteeghii

Correct Citation of this Article

Setyowati, F.M., 1998. Parkia R. Br.. In: Sosef, M.S.M., Hong, L.T. and Prawirohatmodjo, S. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

Selection of Species

The following species in this genus are important in this commodity group and are treated separatedly in this database:

Parkia singularis

Parkia speciosa

Parkia sumatrana

Parkia timoriana

Parkia versteeghii

Parkia singularis

Parkia speciosa

Parkia sumatrana

Parkia timoriana

Parkia versteeghii

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.