Record Number

6224

PROSEA Handbook Number

5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers

Taxon

Sandoricum Cav.

Protologue

Diss. 7: 359 (1789).

Family

MELIACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

x = unknown; S. koetjape: 2n = 16, 22, 28, 32, 44

Vernacular Names

Sentul (trade name). Katon (En). Brunei: kalampu, kelampu. Indonesia: kecapi. Malaysia: kecapi, sentol (general), kelampu (Sabah, Sarawak), langsat kera (Sarawak). Philippines: santol, santor. Burma (Myanmar): thitto. Cambodia: kompeng reach. Laos: tong2. Thailand: kra thon. Vietnam: s[aa][us]-dau, su, xoan dau.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Sandoricum comprises 5 species, four of which are restricted to western Malesia. The fifth, S. koetjape, is commonly cultivated mainly for its fruit and frequently naturalized from India, Burma (Myanmar) and Indo-China to Thailand, the whole of the Malesian region, and tropical Australia and even in the New World tropics. Timber plantations of S. koetjape have been established in Burma (Myanmar).

Uses

The wood of Sandoricum is used for house construction, furniture, cabinet work, joinery, interior construction, shop fitting, panelling, planking and decking of boats, scantlings, carving, butchers' chopping blocks, packing cases, household implements, agricultural implements and sandals. The wood is also used for the production of veneer and plywood, blockboard, and for pulp and paper. It yields a good-quality charcoal, and is used as firewood in Indonesia.

S. koetjape is a well-known fruit tree, the fruits being eaten fresh or processed into jam and chutney. The fruits of the other Sandoricum species are edible but less palatable. S. koetjape is also an excellent shade tree with ornamental value, is planted as an avenue tree, and is suitable for use in shelter-belts. Its pounded leaves are sudorific when applied to the skin and are used to make a decoction against diarrhoea and fever. The powdered bark is an effective treatment for ringworm, shows anti-cancer activity, and has been used for tanning fishing nets. The roots are employed as an anti-diarrhetic, anti-spasmodic, carminative, stomachic and are prescribed as a general tonic after childbirth. Limonoids isolated from the seeds showed insecticidal activity. Fruits of S. borneense have been used as fish bait in Sarawak.

S. koetjape is a well-known fruit tree, the fruits being eaten fresh or processed into jam and chutney. The fruits of the other Sandoricum species are edible but less palatable. S. koetjape is also an excellent shade tree with ornamental value, is planted as an avenue tree, and is suitable for use in shelter-belts. Its pounded leaves are sudorific when applied to the skin and are used to make a decoction against diarrhoea and fever. The powdered bark is an effective treatment for ringworm, shows anti-cancer activity, and has been used for tanning fishing nets. The roots are employed as an anti-diarrhetic, anti-spasmodic, carminative, stomachic and are prescribed as a general tonic after childbirth. Limonoids isolated from the seeds showed insecticidal activity. Fruits of S. borneense have been used as fish bait in Sarawak.

Production and International Trade

The annual production of Sandoricum wood in Thailand at the end of the 1970s was estimated at 12 000 m3; part of this was exported to Great Britain. In Europe the timber has been applied for furniture and interior finishing. In Malaysia, and probably also elsewhere, the timber is traded in mixed consignments of medium-weight hardwood.

Properties

Sandoricum yields a lightweight to medium-weight hardwood with a density of 290-590 kg/m3 at 15% moisture content. Heartwood pale red, yellowish-red or yellow-brown with a pink tinge, indistinct or distinguishable from the pale white or pinkish sapwood; grain straight or slightly wavy; texture moderately fine to slightly coarse and even; wood occasionally with fiddle-back figure, with characteristic faint odour, especially when fresh. Growth rings mostly indistinct, when distinct sometimes marked by a narrow marginal parenchyma band; vessels small to medium-sized, solitary and in radial multiples of 2-3, gum-like deposits sometimes present; parenchyma moderately abundant, paratracheal vasicentric, aliform to confluent, sometimes apotracheal diffuse, occasionally in narrow marginal bands; rays moderately fine, barely visible to the naked eye; ripple marks absent; axial traumatic canals occasionally present.

Shrinkage upon seasoning is low to high; the wood seasons well and is not subject to checking and splitting, although material from Sarawak was difficult to dry due to uneven shrinkage with a tendency to collapse. The wood is moderately soft to moderately hard, fairly weak to moderately strong. It is easy to saw and and can be planed and finished with good results, occasionally a little furry, and takes a high polish. The wood is non-durable when exposed to the weather or in contact with the ground, fairly durable under cover. The heartwood is resistant but sapwood amenable to preservative treatment. The wood is susceptible to marine borer attack and moderately resistant to insect attack. The sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus.

The stem of S. koetjape yields anti-cancer compounds (triterpenes), and anti-feedant compounds (limonoids) have been extracted from its seed. The gross energy value of the sapwood is 19 780 kJ/kg. The mean fibre length of wood of S. koetjape is 1.65 mm.

See also the table on microscopic wood anatomy.

Shrinkage upon seasoning is low to high; the wood seasons well and is not subject to checking and splitting, although material from Sarawak was difficult to dry due to uneven shrinkage with a tendency to collapse. The wood is moderately soft to moderately hard, fairly weak to moderately strong. It is easy to saw and and can be planed and finished with good results, occasionally a little furry, and takes a high polish. The wood is non-durable when exposed to the weather or in contact with the ground, fairly durable under cover. The heartwood is resistant but sapwood amenable to preservative treatment. The wood is susceptible to marine borer attack and moderately resistant to insect attack. The sapwood is susceptible to Lyctus.

The stem of S. koetjape yields anti-cancer compounds (triterpenes), and anti-feedant compounds (limonoids) have been extracted from its seed. The gross energy value of the sapwood is 19 780 kJ/kg. The mean fibre length of wood of S. koetjape is 1.65 mm.

See also the table on microscopic wood anatomy.

Botany

Semi-deciduous, small to large trees, up to 45(-50) m tall; bole sometimes straight, but often crooked or fluted, branchless for up to 18(-21) m, up to 75(-100) cm in diameter, usually with buttresses up to 3 m high; bark surface smooth or sometimes flaky or fissured, lenticellate, greyish to pale pinkish-brown, inner bark pale brown or red-brown to pink, exuding a milky latex; crown rather compact. Leaves arranged spirally, 3-foliolate, exstipulate; leaflets entire. Flowers in an axillary thyrse, bisexual, 4-5-merous; calyx truncate to shallowly lobed; petals free; staminal tube cylindrical, carrying 10 anthers; disk tubular; ovary superior, 4-5-locular with 2 ovules in each cell, style-head lobed. Fruit a 1-5-locular drupe; pyrenes 1(-2)-seeded. Seed without aril. Seedling with epigeal germination; cotyledons emergent; hypocotyl elongated; first pair of leaves opposite, 3-foliolate, subsequent pairs alternate.

Seedling growth is fast and flowering starts after 5-7 years, whereas clonally propagated trees may flower already after 3-4 years. Trees are semi-deciduous after a prolonged dry spell, rarely becoming completely leafless. New leaves develop rapidly and flowers appear shortly after the development of new shoots. S. koetjape trees flower annually and in Peninsular Malaysia the flowering period is so reliable in its timing that it was formerly the signal for the planting of rice. Pollination is by insects. Fruit maturation takes about 5 months, but other reports mention only 2-3 months. In the Philippines ripe fruits are present from June to October, and in Thailand from May to July. It has been suggested that bats disperse S. koetjape seed. S. koetjape is known to form vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae.

S. koetjape is highly variable and was formerly divided into 2 or 3 species, often associated with the "red sentol"" and "yellow sentol"" based on the colour of the old leaves. As there appeared to be no correlation with other characters, the distinction could not be upheld.

Seedling growth is fast and flowering starts after 5-7 years, whereas clonally propagated trees may flower already after 3-4 years. Trees are semi-deciduous after a prolonged dry spell, rarely becoming completely leafless. New leaves develop rapidly and flowers appear shortly after the development of new shoots. S. koetjape trees flower annually and in Peninsular Malaysia the flowering period is so reliable in its timing that it was formerly the signal for the planting of rice. Pollination is by insects. Fruit maturation takes about 5 months, but other reports mention only 2-3 months. In the Philippines ripe fruits are present from June to October, and in Thailand from May to July. It has been suggested that bats disperse S. koetjape seed. S. koetjape is known to form vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae.

S. koetjape is highly variable and was formerly divided into 2 or 3 species, often associated with the "red sentol"" and "yellow sentol"" based on the colour of the old leaves. As there appeared to be no correlation with other characters, the distinction could not be upheld.

Image

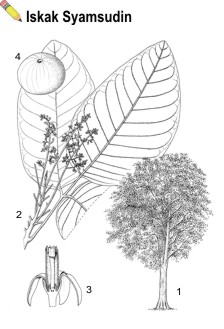

| Sandoricum koetjape (Burm. f.) Merr. – 1, tree habit; 2, flowering twig; 3, sectioned flower; 4, fruit. |

Ecology

Sandoricum occurs scattered in primary or sometimes secondary rain forest, up to 1200 m altitude. S. koetjape has been reported from lowland dipterocarp forest but also from kerangas on podzolic soils in both perhumid and seasonal climates. S. beccarianum is locally co-dominant in peat-swamp forest.

Silviculture and Management

Sandoricum can be propagated by seed, but S. koetjape is also propagated by vegetative means like budding, grafting, inarching and marcotting. Seed, however, can not be stored for any length of time. S. koetjape seed with or without the adhering pulp have 90-95% germination in 16-31 days. The density of S. koetjape trees of over 40 cm diameter in natural forest in Peninsular Malaysia is 2.0 per 100 ha.

Genetic Resources and Breeding

Various cultivars of the fruit tree S. koetjape exist, including tetraploid ones. Important tree collections are held in the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand.

Prospects

Little is known on the silviculture of Sandoricum and, as the wood quality is only moderate, it is not very likely that its wood will be increasingly used for sawn timber.

Literature

[57]Appanah, S. & Weinland, G., 1993. Planting quality timber trees in Peninsular Malaysia - a review. Malayan Forest Record No 38. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 221 pp.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[209]Corner, E.J.H., 1988. Wayside trees of Malaya. 3rd edition. 2 volumes. The Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur. 774 pp.

[218]Dahms, K.-G., 1982. Asiatische, ozeanische und australische Exporthölzer [Asiatic, Pacific and Australian export timbers]. DRW-Verlag, Stuttgart. 304 pp.

[238]de Vogel, E.F., 1980. Seedlings of dicotyledons. Structure, development, types. Descriptions of 150 woody Malesian taxa. Pudoc, Wageningen. 465 pp.

[260]den Berger, L.G., 1926. Houtsoorten der cultuurgebieden van Java en Sumatra's oostkust [Tree species of the cultivated areas of Java and the east coast of Sumatra]. Mededeelingen No 13. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[278]Docters van Leeuwen, W.M., 1935. The dispersal of plants by fruit-eating bats. Gardens' Bulletin, Straits Settlements 9: 58-63.

[341]Flora Malesiana (various editors), 1950-. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Boston, London.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[464]Ilic, J., 1990. The CSIRO macro key for hardwood identification. CSIRO, Highett. 125 pp.

[521]Kaneda, N. et al., 1992. Plant anticancer agents. L. Cytotoxic triterpenes from Sandoricum koetjape stems. Journal of Natural Products 55(5): 654-659.

[536]Keating, W.G. & Bolza, E., 1982. Characteristics, properties and uses of timbers. Vol. 1. South-East Asia, northern Australia and the Pacific. Inkata Press Proprietary Ltd., Melbourne, Sydney & London. 362 pp.

[729]Mabberley, D.J., 1985. Flora Malesianae praecursores LXVII. Meliaceae (divers genera). Blumea 31: 129-152.

[780]Meniado, J.A. et al., 1975-1981. Wood identification handbook for Philippine timbers. 2 volumes. Government Printing Office, Manila. 370 pp. & 186 pp.

[825]Ng, F.S.P., 1978. Strategies of establishment in Malayan forest trees. In: Tomlinson, P.B. & Zimmermann, M.H. (Editors): Tropical trees as living systems. The proceedings of the fourth Cabot symposium held at Harvard Forest, Petersham, Massachusetts on April 26-30, 1976. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, London, New York, Melbourne. pp. 129-162.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[861]Oey Djoen Seng, 1951. De soortelijke gewichten van Indonesische houtsoorten en hun betekenis voor de praktijk [Specific gravity of Indonesian woods and its significance for practical use]. Rapport No 46. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 183 pp.

[867]Paredes, E.P. & Leano, R.M., 1993. Survey of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae in selected fruit trees. Philippine Phytopathology 29(1-2): 104.

[878]Pennington, T.D. & Styles, B.T., 1975. A generic monograph of the Meliaceae. Blumea 22: 419-540.

[900]Powell, R.G. et al., 1991. Limonoid antifeedants from seed of Sandoricum koetjape. Journal of Natural Products 54(1): 241-246.

[908]Priasukmana, S. & Silitonga, T., 1972. Dimensi serat beberapa jenis kayu Jawa Barat [Fiber dimensions of several timber species from West Java]. Laporan No 2. Lembaga Penelitian Hasil Hutan, Bogor. 42 pp.

[933]Research Institute of Wood Industry, 1988. Identification, properties and uses of some Southeast Asian woods. Chinese Academy of Forestry, Wan Shou Shan, Beijing & International Tropical Timber Organization, Yokohama. 201 pp.

[934]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[947]Rierink, A., 1938. Over de caloriemetrische verbrandingswaarde van een zestigtal Ned. Indische houtsoorten [The calorific value of about 60 woods from the Dutch East Indies]. Tectona 31: 400-418.

[977]Sarawak Timber Industry Development Corporation, 1987. Manual of Sarawak timber species. Properties and uses. Sarawak Timber Industry Development Corporation, Kuching. 97 pp.

[1038]Smitinand, T., 1980. Thai plant names. Royal Forest Department, Bangkok. 379 pp.

[1040]Smythies, B.E., 1965. Common Sarawak trees. Borneo Literature Bureau, South China Morning Post, Hong Kong. 153 pp.

[1052]Stadelman, R.C., 1966. Forests of Southeast Asia. Princeton, Memphis, Tennessee. 245 pp.

[1065]Styles, B.T. & Khosla, P.K., 1976. Cytology and reproductive biology of Meliaceae. In: Burley, J. & Styles, B.T. (Editors): Tropical trees. Variation, breeding and conservation. Linnean Society Symposium Series No 2. Academic Press, London. pp. 61-67.

[1098]Timber Research and Development Association, 1979. Timbers of the world. Volume 1. Africa, S. America, Southern Asia, S.E. Asia. TRADA/The Construction Press, Lancaster. 463 pp.

[1123]van der Pijl, L., 1957. The dispersal of plants by bats (chiropterochory). Acta Botanica Neerlandica 6: 291-315.

[1164]Verheij, E.W.M. & Coronel, R.E. (Editors), 1991. Plant resources of South-East Asia No 2. Edible fruits and nuts. Pudoc, Wageningen. 446 pp.

[1169]Vidal, J., 1962. Noms vernaculaires de plantes en usage au Laos [Vernacular names of plants used in Laos]. Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, Paris. 197 pp.

[1213]Whitmore, T.C., 1975. Tropical rain forests of the Far East. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 282 pp.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1232]Wisse, J.H., 1965. Volumegewichten van een aantal houtmonsters uit West Nieuw Guinea [Specific gravity of some wood samples from West New Guinea]. Afdeling Bosexploitatie en Boshuishoudkunde, Landbouwhogeschool, Wageningen. 23 pp.

[1239]Wong, T.M., 1976. Wood structure of the lesser known timbers of Peninsular Malaysia. Malayan Forest Records No 28. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. xi + 115 pp.

[1242]Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 30. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 259 pp.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[209]Corner, E.J.H., 1988. Wayside trees of Malaya. 3rd edition. 2 volumes. The Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur. 774 pp.

[218]Dahms, K.-G., 1982. Asiatische, ozeanische und australische Exporthölzer [Asiatic, Pacific and Australian export timbers]. DRW-Verlag, Stuttgart. 304 pp.

[238]de Vogel, E.F., 1980. Seedlings of dicotyledons. Structure, development, types. Descriptions of 150 woody Malesian taxa. Pudoc, Wageningen. 465 pp.

[260]den Berger, L.G., 1926. Houtsoorten der cultuurgebieden van Java en Sumatra's oostkust [Tree species of the cultivated areas of Java and the east coast of Sumatra]. Mededeelingen No 13. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[278]Docters van Leeuwen, W.M., 1935. The dispersal of plants by fruit-eating bats. Gardens' Bulletin, Straits Settlements 9: 58-63.

[341]Flora Malesiana (various editors), 1950-. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Boston, London.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[464]Ilic, J., 1990. The CSIRO macro key for hardwood identification. CSIRO, Highett. 125 pp.

[521]Kaneda, N. et al., 1992. Plant anticancer agents. L. Cytotoxic triterpenes from Sandoricum koetjape stems. Journal of Natural Products 55(5): 654-659.

[536]Keating, W.G. & Bolza, E., 1982. Characteristics, properties and uses of timbers. Vol. 1. South-East Asia, northern Australia and the Pacific. Inkata Press Proprietary Ltd., Melbourne, Sydney & London. 362 pp.

[729]Mabberley, D.J., 1985. Flora Malesianae praecursores LXVII. Meliaceae (divers genera). Blumea 31: 129-152.

[780]Meniado, J.A. et al., 1975-1981. Wood identification handbook for Philippine timbers. 2 volumes. Government Printing Office, Manila. 370 pp. & 186 pp.

[825]Ng, F.S.P., 1978. Strategies of establishment in Malayan forest trees. In: Tomlinson, P.B. & Zimmermann, M.H. (Editors): Tropical trees as living systems. The proceedings of the fourth Cabot symposium held at Harvard Forest, Petersham, Massachusetts on April 26-30, 1976. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, London, New York, Melbourne. pp. 129-162.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[861]Oey Djoen Seng, 1951. De soortelijke gewichten van Indonesische houtsoorten en hun betekenis voor de praktijk [Specific gravity of Indonesian woods and its significance for practical use]. Rapport No 46. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 183 pp.

[867]Paredes, E.P. & Leano, R.M., 1993. Survey of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae in selected fruit trees. Philippine Phytopathology 29(1-2): 104.

[878]Pennington, T.D. & Styles, B.T., 1975. A generic monograph of the Meliaceae. Blumea 22: 419-540.

[900]Powell, R.G. et al., 1991. Limonoid antifeedants from seed of Sandoricum koetjape. Journal of Natural Products 54(1): 241-246.

[908]Priasukmana, S. & Silitonga, T., 1972. Dimensi serat beberapa jenis kayu Jawa Barat [Fiber dimensions of several timber species from West Java]. Laporan No 2. Lembaga Penelitian Hasil Hutan, Bogor. 42 pp.

[933]Research Institute of Wood Industry, 1988. Identification, properties and uses of some Southeast Asian woods. Chinese Academy of Forestry, Wan Shou Shan, Beijing & International Tropical Timber Organization, Yokohama. 201 pp.

[934]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[947]Rierink, A., 1938. Over de caloriemetrische verbrandingswaarde van een zestigtal Ned. Indische houtsoorten [The calorific value of about 60 woods from the Dutch East Indies]. Tectona 31: 400-418.

[977]Sarawak Timber Industry Development Corporation, 1987. Manual of Sarawak timber species. Properties and uses. Sarawak Timber Industry Development Corporation, Kuching. 97 pp.

[1038]Smitinand, T., 1980. Thai plant names. Royal Forest Department, Bangkok. 379 pp.

[1040]Smythies, B.E., 1965. Common Sarawak trees. Borneo Literature Bureau, South China Morning Post, Hong Kong. 153 pp.

[1052]Stadelman, R.C., 1966. Forests of Southeast Asia. Princeton, Memphis, Tennessee. 245 pp.

[1065]Styles, B.T. & Khosla, P.K., 1976. Cytology and reproductive biology of Meliaceae. In: Burley, J. & Styles, B.T. (Editors): Tropical trees. Variation, breeding and conservation. Linnean Society Symposium Series No 2. Academic Press, London. pp. 61-67.

[1098]Timber Research and Development Association, 1979. Timbers of the world. Volume 1. Africa, S. America, Southern Asia, S.E. Asia. TRADA/The Construction Press, Lancaster. 463 pp.

[1123]van der Pijl, L., 1957. The dispersal of plants by bats (chiropterochory). Acta Botanica Neerlandica 6: 291-315.

[1164]Verheij, E.W.M. & Coronel, R.E. (Editors), 1991. Plant resources of South-East Asia No 2. Edible fruits and nuts. Pudoc, Wageningen. 446 pp.

[1169]Vidal, J., 1962. Noms vernaculaires de plantes en usage au Laos [Vernacular names of plants used in Laos]. Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, Paris. 197 pp.

[1213]Whitmore, T.C., 1975. Tropical rain forests of the Far East. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 282 pp.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1232]Wisse, J.H., 1965. Volumegewichten van een aantal houtmonsters uit West Nieuw Guinea [Specific gravity of some wood samples from West New Guinea]. Afdeling Bosexploitatie en Boshuishoudkunde, Landbouwhogeschool, Wageningen. 23 pp.

[1239]Wong, T.M., 1976. Wood structure of the lesser known timbers of Peninsular Malaysia. Malayan Forest Records No 28. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. xi + 115 pp.

[1242]Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 30. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 259 pp.

Author(s)

Salma Idris

Sandoricum beccarianum

Sandoricum borneense

Sandoricum koetjape

Sandoricum borneense

Sandoricum koetjape

Correct Citation of this Article

Idris, S., 1998. Sandoricum Cav.. In: Sosef, M.S.M., Hong, L.T. and Prawirohatmodjo, S. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

Selection of Species

The following species in this genus are important in this commodity group and are treated separatedly in this database:

Sandoricum beccarianum

Sandoricum borneense

Sandoricum koetjape

Sandoricum beccarianum

Sandoricum borneense

Sandoricum koetjape

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.