Record Number

6418

PROSEA Handbook Number

5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers

Taxon

Tristaniopsis Brongn. & Gris

Protologue

Bull. Soc. Bot. France 10: 371 (1863).

Family

MYRTACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

x = unknown; T. laurina (J.E. Smith) Peter G. Wilson & J.T. Waterh.: 2n = 22

Vernacular Names

Brunei: selan. Indonesia: pelawan (general). Malaysia: keruntum, pelawan (general), melaban, selunsur (Sarawak). Papua New Guinea: Papua New Guinea swamp box, swamp mahogany. Philippines: malabayabas (Filipino). Burma (Myanmar): duakyat. Thailand: tamsao-nu.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Tristaniopsis is a fairly large genus of about 45 species which occur from Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand, throughout the Malesian region (except central and eastern Java and the Lesser Sunda Islands), to eastern Australia and New Caledonia. About 20 species occur within Malesia.

Uses

The hard and durable wood of Tristaniopsis is used for heavy constructional work, e.g. for posts and beams for house and bridge construction, wharves and jetties, sleepers, poles, piling, heavy duty flooring, exterior decking, tool handles, mauls and mallets, spokes and wheels, pulleys, bearings, rollers, saw guide blocks, bowling balls, transmission poles and stakes for pepper support. It is sometimes used for paddles, rice pestles, and for high-quality firewood or charcoal.

In Sulawesi an unknown species of Tristaniopsis has been planted as a fire-break in Pinus merkusii Jungh. & de Vriese plantations.

In Sulawesi an unknown species of Tristaniopsis has been planted as a fire-break in Pinus merkusii Jungh. & de Vriese plantations.

Production and International Trade

Export of Tristaniopsis has been mainly between Asian Pacific countries, the main consumer being Australia. It is occasionally exported to Japan. In Papua New Guinea Tristaniopsis timber is traded together with that of Lophostemon and Welchiodendron as "Papua New Guinea swamp box"" of which only 150 m3 was exported at an average free-on-board (FOB) price of US$ 101/m3 in 1996.

Properties

Tristaniopsis yields a heavy hardwood with a density of 865-1250 kg/m3 at 15% moisture content. Heartwood pink-brown, red-brown or purple-grey-brown, only occasionally distinct from the paler sapwood; grain interlocked, sometimes wavy; texture fine and even; wood sometimes with some silver grain. Growth rings indistinct, larger vessels with tendency to align in concentric rings; vessels rather variable in size, from very small to medium-sized, almost exclusively solitary, usually in oblique arrangement, with reddish gum-like deposits or blocked by tyloses; parenchyma sparse, paratracheal and apotracheal diffuse tending to short tangential bands, hardly visible with a hand lens; rays very fine, visible with a hand lens; ripple marks absent.

Shrinkage of the wood upon seasoning is variable, from moderate to very high. It takes about 5 months to air dry boards 40 mm thick during which time the wood is subject to warping (particularly back-sawn boards), distortion and surface checking (not severe relative to its density). Partial air drying to 30% moisture content before kiln drying and a final reconditioning treatment is recommended. In Malaysia kiln-drying schedule D is recommended. The wood is very hard, very strong and tough. It is fairly difficult to work due to its hardness and high silica content. Tool edges blunt rapidly and sawing is especially difficult. The wood can be planed to a relatively smooth surface, although a reduced cutting angle of 15-20° may be necessary. It turns excellently. Pre-boring is necessary before nailing. Bending of T. decorticata is rated as fair for boards 2.5 cm thick and very good for boards 0.3 cm thick. The wood is durable to extremely durable when exposed to the weather or in contact with the ground. It is resistant to termite and marine borer attack, whereas the sapwood is non-susceptible to Lyctus. The heartwood is extremely resistant to impregnation.

See also the tables on microscopic wood anatomy and wood properties.

Shrinkage of the wood upon seasoning is variable, from moderate to very high. It takes about 5 months to air dry boards 40 mm thick during which time the wood is subject to warping (particularly back-sawn boards), distortion and surface checking (not severe relative to its density). Partial air drying to 30% moisture content before kiln drying and a final reconditioning treatment is recommended. In Malaysia kiln-drying schedule D is recommended. The wood is very hard, very strong and tough. It is fairly difficult to work due to its hardness and high silica content. Tool edges blunt rapidly and sawing is especially difficult. The wood can be planed to a relatively smooth surface, although a reduced cutting angle of 15-20° may be necessary. It turns excellently. Pre-boring is necessary before nailing. Bending of T. decorticata is rated as fair for boards 2.5 cm thick and very good for boards 0.3 cm thick. The wood is durable to extremely durable when exposed to the weather or in contact with the ground. It is resistant to termite and marine borer attack, whereas the sapwood is non-susceptible to Lyctus. The heartwood is extremely resistant to impregnation.

See also the tables on microscopic wood anatomy and wood properties.

Botany

Shrubs or small, medium-sized to large trees up to 45 m tall; bole up to 70(-120) cm in diameter, buttresses absent; bark surface smooth, often peeling off in large, spiral, scroll-like pieces, usually accumulating round the base of the trunk, orange-brown to pinkish-grey, inner bark whitish or yellowish. Leaves alternate, simple, entire, with glandular dots and an intramarginal vein; stipules absent. Inflorescence axillary, cymose. Flowers 5-merous; calyx lobes persistent; petals free, white or yellow; stamens numerous, fused into fascicles opposite the petals; ovary half-inferior to superior, (2-)3-locular with numerous pendulous ovules, style filiform with a capitate stigma. Fruit a loculicidal capsule, exserted from the hypanthium, hemispherical in the upper part, with a distinctive column at the centre of the dehisced fruit. Seed usually winged, with a straight embryo and convolute or obvolute, reniform cotyledons. Seedling with epigeal germination; cotyledons leafy, 2-lobed; leaves convolute.

Mass-flowering with intervals of several years has been reported for T. micrantha in the Philippines. It has been suggested that sudden changes in temperature may initiate flowering. The flowering trees are mostly leafless. The fruits burst open with some force, slightly scattering the seeds. After the fruits burst, young leaves develop. Young leaves are often pink, old withered leaves red.

Recent studies revealed that Tristania sensu lato is heterogeneous and it was split into 5 genera: Lophostemon (4 species), Ristantia (3 species), Tristania sensu stricto (1 species, restricted to Australia), Welchiodendron (1 species), and Tristaniopsis (comprising the majority of species, including all western Malesian ones formerly referred to as Tristania spp.). Tristaniopsis is distinguished from the other genera particularly by the combination of its alternate leaves, its fruit exserted from the hypanthium and its winged seeds.

Mass-flowering with intervals of several years has been reported for T. micrantha in the Philippines. It has been suggested that sudden changes in temperature may initiate flowering. The flowering trees are mostly leafless. The fruits burst open with some force, slightly scattering the seeds. After the fruits burst, young leaves develop. Young leaves are often pink, old withered leaves red.

Recent studies revealed that Tristania sensu lato is heterogeneous and it was split into 5 genera: Lophostemon (4 species), Ristantia (3 species), Tristania sensu stricto (1 species, restricted to Australia), Welchiodendron (1 species), and Tristaniopsis (comprising the majority of species, including all western Malesian ones formerly referred to as Tristania spp.). Tristaniopsis is distinguished from the other genera particularly by the combination of its alternate leaves, its fruit exserted from the hypanthium and its winged seeds.

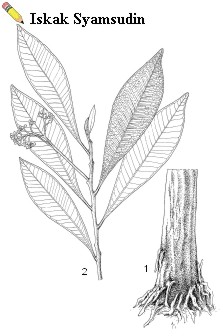

Image

| Tristaniopsis whiteana (Griffith) Peter G. Wilson & J.T. Waterh. – 1, trunk base; 2, flowering twig. |

Ecology

Tristaniopsis species occur in many different types of lowland to lower montane forest up to 1300 m altitude, often along rivers or near the coast, but also in rocky locations. They are often common but do not occur gregariously. Some species, such as T. whiteana, grow especially on landslides and open patches along streams, and in secondary forest and are evidently efficient colonizers. They often grow together with Cratoxylum species.

Silviculture and Management

Tristaniopsis may be propagated by seed. The number of dry seeds of T. obovata is about 1.4 million. In a germination trial seed of T. merguensis germinated for 70-85% in 13-22 days. In Java Tristaniopsis has been planted above 1000 m altitude.

Genetic Resources and Breeding

Tristaniopsis trees do not seem to be subject to extensive logging as the timber is mainly used locally and has no great economic importance. The supply in the forest still seems to be considerable for many species.

Prospects

As the demand for very hard wood for specialty use is increasing in Europe and a fair supply can be generated from parts of Sarawak and Indonesia, Tristaniopsis may be expected to gain importance as an export timber.

Literature

[1]Abdul Khalid Che Din, 1985. Malaysian timbers - pelawan. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 100. Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 5 pp.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[154]Bruzon, J.B., 1982. Gregarious flowering of toog and bono. Canopy International 8(9): 9-10.

[162]Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Sabah Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Sabah, Sandakan. xviii + 501 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[209]Corner, E.J.H., 1988. Wayside trees of Malaya. 3rd edition. 2 volumes. The Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur. 774 pp.

[218]Dahms, K.-G., 1982. Asiatische, ozeanische und australische Exporthölzer [Asiatic, Pacific and Australian export timbers]. DRW-Verlag, Stuttgart. 304 pp.

[235]de Guzman, E.D., Umali, R.M. & Sotalbo, E.D., 1986. Guide to the Philippine flora and fauna. Vol. 3: Dipterocarps, non-dipterocarps. Natural Resources Management Centre, Ministry of Natural Resources, Quezon City & University of the Philippines, Los Baños. xx + 414 pp.

[260]den Berger, L.G., 1926. Houtsoorten der cultuurgebieden van Java en Sumatra's oostkust [Tree species of the cultivated areas of Java and the east coast of Sumatra]. Mededeelingen No 13. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[296]Eala, R.C., 1975. Machining properties of malabayabas (Tristania decorticata Merr.). Forpride Digest 4: 64-66.

[300]Eddowes, P.J., 1977. Commercial timbers of Papua New Guinea, their properties and uses. Forest Products Research Centre, Department of Primary Industry, Port Moresby. xiv + 195 pp.

[302]Eddowes, P.J., 1980. Lesser known timber species of SEALPA countries. A review and summary. South East Asia Lumber Producers' Association, Jakarta. 132 pp.

[360]Fundter, J.M. & Wisse, J.H., 1977. 40 belangrijke houtsoorten uit Indonesisch Nieuw Guinea (Irian Jaya) met de anatomische en technische kenmerken [40 important timber species from Indonesian New Guinea (Irian Jaya) with their anatomical and technical characteristics]. Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen 77-9. 223 pp.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[487]Japing, C.H., 1961. Houtsoorten van Nieuw Guinea - literatuurstudie [Tree species of Dutch New Guinea - survey of literature]. 2 parts. Wageningen. 220 pp.

[536]Keating, W.G. & Bolza, E., 1982. Characteristics, properties and uses of timbers. Vol. 1. South-East Asia, northern Australia and the Pacific. Inkata Press Proprietary Ltd., Melbourne, Sydney & London. 362 pp.

[775]Mendoza, E.U., 1975. Bending properties of malabayabas (Tristania decorticata Merr.). Forpride Digest 4: 66-68.

[780]Meniado, J.A. et al., 1975-1981. Wood identification handbook for Philippine timbers. 2 volumes. Government Printing Office, Manila. 370 pp. & 186 pp.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[861]Oey Djoen Seng, 1951. De soortelijke gewichten van Indonesische houtsoorten en hun betekenis voor de praktijk [Specific gravity of Indonesian woods and its significance for practical use]. Rapport No 46. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 183 pp.

[934]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[1023]Sjape'ie, I., 1954. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of various fruits and seeds]. Korte mededeling 20A. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 10 pp.

[1040]Smythies, B.E., 1965. Common Sarawak trees. Borneo Literature Bureau, South China Morning Post, Hong Kong. 153 pp.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1230]Wilson, P.G. & Waterhouse, J.T., 1982. A review of the genus Tristania R. Br. (Myrtaceae): a heterogeneous assemblage of five genera. Australian Journal of Botany 30: 413-446.

[1239]Wong, T.M., 1976. Wood structure of the lesser known timbers of Peninsular Malaysia. Malayan Forest Records No 28. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. xi + 115 pp.

[1242]Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 30. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 259 pp.

[1274]Zwart, W.G.J., 1928. Herbebosschingswerk in Bagelen 1875-1925 [Reforestation in Bagelen, 1875-1925]. Mededeelingen No 17. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 233 pp.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[154]Bruzon, J.B., 1982. Gregarious flowering of toog and bono. Canopy International 8(9): 9-10.

[162]Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Sabah Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Sabah, Sandakan. xviii + 501 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[209]Corner, E.J.H., 1988. Wayside trees of Malaya. 3rd edition. 2 volumes. The Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur. 774 pp.

[218]Dahms, K.-G., 1982. Asiatische, ozeanische und australische Exporthölzer [Asiatic, Pacific and Australian export timbers]. DRW-Verlag, Stuttgart. 304 pp.

[235]de Guzman, E.D., Umali, R.M. & Sotalbo, E.D., 1986. Guide to the Philippine flora and fauna. Vol. 3: Dipterocarps, non-dipterocarps. Natural Resources Management Centre, Ministry of Natural Resources, Quezon City & University of the Philippines, Los Baños. xx + 414 pp.

[260]den Berger, L.G., 1926. Houtsoorten der cultuurgebieden van Java en Sumatra's oostkust [Tree species of the cultivated areas of Java and the east coast of Sumatra]. Mededeelingen No 13. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 186 pp.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[296]Eala, R.C., 1975. Machining properties of malabayabas (Tristania decorticata Merr.). Forpride Digest 4: 64-66.

[300]Eddowes, P.J., 1977. Commercial timbers of Papua New Guinea, their properties and uses. Forest Products Research Centre, Department of Primary Industry, Port Moresby. xiv + 195 pp.

[302]Eddowes, P.J., 1980. Lesser known timber species of SEALPA countries. A review and summary. South East Asia Lumber Producers' Association, Jakarta. 132 pp.

[360]Fundter, J.M. & Wisse, J.H., 1977. 40 belangrijke houtsoorten uit Indonesisch Nieuw Guinea (Irian Jaya) met de anatomische en technische kenmerken [40 important timber species from Indonesian New Guinea (Irian Jaya) with their anatomical and technical characteristics]. Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen 77-9. 223 pp.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[487]Japing, C.H., 1961. Houtsoorten van Nieuw Guinea - literatuurstudie [Tree species of Dutch New Guinea - survey of literature]. 2 parts. Wageningen. 220 pp.

[536]Keating, W.G. & Bolza, E., 1982. Characteristics, properties and uses of timbers. Vol. 1. South-East Asia, northern Australia and the Pacific. Inkata Press Proprietary Ltd., Melbourne, Sydney & London. 362 pp.

[775]Mendoza, E.U., 1975. Bending properties of malabayabas (Tristania decorticata Merr.). Forpride Digest 4: 66-68.

[780]Meniado, J.A. et al., 1975-1981. Wood identification handbook for Philippine timbers. 2 volumes. Government Printing Office, Manila. 370 pp. & 186 pp.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[861]Oey Djoen Seng, 1951. De soortelijke gewichten van Indonesische houtsoorten en hun betekenis voor de praktijk [Specific gravity of Indonesian woods and its significance for practical use]. Rapport No 46. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 183 pp.

[934]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[1023]Sjape'ie, I., 1954. Gewicht en volume van verschillende vrucht- en zaadsoorten [Weight and volume of various fruits and seeds]. Korte mededeling 20A. Bosbouwproefstation, Bogor. 10 pp.

[1040]Smythies, B.E., 1965. Common Sarawak trees. Borneo Literature Bureau, South China Morning Post, Hong Kong. 153 pp.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1230]Wilson, P.G. & Waterhouse, J.T., 1982. A review of the genus Tristania R. Br. (Myrtaceae): a heterogeneous assemblage of five genera. Australian Journal of Botany 30: 413-446.

[1239]Wong, T.M., 1976. Wood structure of the lesser known timbers of Peninsular Malaysia. Malayan Forest Records No 28. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. xi + 115 pp.

[1242]Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 30. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 259 pp.

[1274]Zwart, W.G.J., 1928. Herbebosschingswerk in Bagelen 1875-1925 [Reforestation in Bagelen, 1875-1925]. Mededeelingen No 17. Proefstation voor het Boschwezen, Buitenzorg. 233 pp.

Author(s)

E. Boer (general part), R.H.M.J. Lemmens (general part, selection of species)

Tristaniopsis decorticata

Tristaniopsis elliptica

Tristaniopsis ferruginea

Tristaniopsis grandifolia

Tristaniopsis littoralis

Tristaniopsis merguensis

Tristaniopsis micrantha

Tristaniopsis obovata

Tristaniopsis whiteana

Tristaniopsis elliptica

Tristaniopsis ferruginea

Tristaniopsis grandifolia

Tristaniopsis littoralis

Tristaniopsis merguensis

Tristaniopsis micrantha

Tristaniopsis obovata

Tristaniopsis whiteana

Correct Citation of this Article

Boer, E. & Lemmens, R.H.M.J., 1998. Tristaniopsis Brongn. & Gris. In: Sosef, M.S.M., Hong, L.T. and Prawirohatmodjo, S. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

Selection of Species

The following species in this genus are important in this commodity group and are treated separatedly in this database:

Tristaniopsis decorticata

Tristaniopsis elliptica

Tristaniopsis ferruginea

Tristaniopsis grandifolia

Tristaniopsis littoralis

Tristaniopsis merguensis

Tristaniopsis micrantha

Tristaniopsis obovata

Tristaniopsis whiteana

Tristaniopsis decorticata

Tristaniopsis elliptica

Tristaniopsis ferruginea

Tristaniopsis grandifolia

Tristaniopsis littoralis

Tristaniopsis merguensis

Tristaniopsis micrantha

Tristaniopsis obovata

Tristaniopsis whiteana

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.