Record Number

6490

PROSEA Handbook Number

5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers

Taxon

Xylocarpus J. König

Protologue

Naturforscher (Halle) 20: 2 (1784).

Family

MELIACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

x = 26; X. granatum, X. moluccensis: 2n = 52

Vernacular Names

Nyireh (trade name). Mangrove cedar, pussur wood (En). Philippines: tabigi (general). Thailand: kra buun, ta buun.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Xylocarpus comprises 3 species and is found along the coasts of East Africa and Madagascar towards India, Burma (Myanmar), Indo-China, China, the Ryukyu Islands, Thailand, the Malesian region, tropical Australia and the Pacific, east to Tonga and Fiji. All three species are widespread and occur throughout Malesia.

Uses

The wood is used mainly for high-quality furniture and cabinet work, carving and the manufacture of fancy articles. Other reported uses are for light construction, bridge building, interior finish and panelling, flooring, doors, posts, joists, beams, rafters, mouldings, ship and boat building, fence posts, salt-water piling, gun stocks, billiard tables and billiard cue butts, tool handles, tobacco pipes, wooden pins and sliced decorative veneer. In India the wood is regarded suitable for second grade pencils. The wood is sometimes used as firewood and for charcoal production, but these applications are not recommended.

The oil extracted from seeds of X. granatum has been used as an illuminant and as hair oil. Burned seeds of the same species have been used mixed with sulphur and coconut oil against itchy skin. An oil extracted from X. moluccensis seeds is used in the Philippines to treat insect bites. A decoction of the bark is used in the treatment of cholera and is also applied to cure dysentery, diarrhoea and other abdominal troubles, and as a febrifuge. Formerly, the bark was used to make a fairly bitter "palm wine"". The bark yields a tannin which has been used quite extensively in Java to tan fishing lines and nets and has been applied to tan heavy hides and to dye cloth umber.

The oil extracted from seeds of X. granatum has been used as an illuminant and as hair oil. Burned seeds of the same species have been used mixed with sulphur and coconut oil against itchy skin. An oil extracted from X. moluccensis seeds is used in the Philippines to treat insect bites. A decoction of the bark is used in the treatment of cholera and is also applied to cure dysentery, diarrhoea and other abdominal troubles, and as a febrifuge. Formerly, the bark was used to make a fairly bitter "palm wine"". The bark yields a tannin which has been used quite extensively in Java to tan fishing lines and nets and has been applied to tan heavy hides and to dye cloth umber.

Production and International Trade

Xylocarpus wood is generally used on a local scale. Very small amounts of "mangrove cedar"" are imported by Japan. In 1996 Papua New Guinea exported only 55 m3 of mangrove cedar logs at an average free-on-board (FOB) price of US$ 107/m3.

Properties

Xylocarpus yields a medium-weight hardwood with a density of 615-880 kg/m3 at 15% moisture content. Heartwood reddish, darkening to a deep warm brown on exposure, usually sharply demarcated from the narrow, buff-coloured, pale pink or silver-grey sapwood; grain straight or alternating to slightly interlocked; texture fine and even; wood with darker streaks producing attractive watered-silk figure on tangential surfaces; X. moluccensis sometimes with a faint cedar-like odour. Growth rings visible or hardly visible, marked by narrow marginal parenchyma; vessels very small to medium-sized, mostly in radial pairs, occasionally solitary or in radial multiples of up to 4 (X. granatum) or more than 4 (X. moluccensis), open or filled with dark-coloured, gum-like deposits; parenchyma sparse to abundant, apotracheal in narrow to moderately broad closely-spaced bands and paratracheal vasicentric; rays moderately fine to medium-sized; fine ripple marks present but not always distinct.

Shrinkage is very low to low, the wood seasons well, but is liable to splitting, end-checking and insect attack. Boards of X. moluccensis take about 3 months to air dry when 13 mm thick and about 5 months when 38 mm thick; the wood kiln dries satisfactorily. The wood is moderately hard, moderately strong and tough. It is easy to work and turn, occasionally it is reported as difficult to saw due to interlocked grain, it finishes well and takes a high polish. The pulping and paper making properties of X. granatum are rated as poor. The wood is moderately durable when exposed to the weather or in contact with the ground, and is resistant to pressure preservative treatment. It is resistant to teredo attack in some situations and to dry-wood termites in protected situations. The sapwood is non-susceptible to Lyctus.

The bark of mature trees contains 20-34% tannin on dry matter base. Seeds contain 1-2% oil. The charcoal has a somewhat low density and high burning rate making Xylocarpus an unfavourable source. Firewood burns quickly and produces great heat, which is why other sources are preferred.

See also the tables on microscopic wood anatomy and wood properties.

Shrinkage is very low to low, the wood seasons well, but is liable to splitting, end-checking and insect attack. Boards of X. moluccensis take about 3 months to air dry when 13 mm thick and about 5 months when 38 mm thick; the wood kiln dries satisfactorily. The wood is moderately hard, moderately strong and tough. It is easy to work and turn, occasionally it is reported as difficult to saw due to interlocked grain, it finishes well and takes a high polish. The pulping and paper making properties of X. granatum are rated as poor. The wood is moderately durable when exposed to the weather or in contact with the ground, and is resistant to pressure preservative treatment. It is resistant to teredo attack in some situations and to dry-wood termites in protected situations. The sapwood is non-susceptible to Lyctus.

The bark of mature trees contains 20-34% tannin on dry matter base. Seeds contain 1-2% oil. The charcoal has a somewhat low density and high burning rate making Xylocarpus an unfavourable source. Firewood burns quickly and produces great heat, which is why other sources are preferred.

See also the tables on microscopic wood anatomy and wood properties.

Botany

Evergreen or sometimes deciduous, monoecious or rarely dioecious, small to medium-sized trees up to 20(-30) m tall; bole crooked (X. granatum) to straight and cylindrical (X. moluccensis), branchless for up to 10 m, up to 90(-100) cm in diameter, usually with small buttresses and snail roots, those of X. moluccensis bearing many short pneumatophores; bark surface smooth, irregularly flaking, whitish to yellow-brown (X. granatum) or rough, longitudinally fissured, flaking into oblong pieces, dark brown (X. moluccensis), inner bark green, red or pink; crown narrow and compact to bushy. Leaves arranged spirally, paripinnate with (1-)2-4(-5) pairs of leaflets, exstipulate; leaflets entire. Flowers in an axillary thyrse, 4-merous; calyx lobed; petals free, pinkish-yellow; staminal tube urceolate to cupular bearing 8 anthers; disk cushion-shaped, red; ovary superior, 4(-5)-locular with 3-4(-6) ovules in each cell, style short with a discoid stigma. Fruit a large, tardily dehiscing, subglobose capsule. Seeds 5-20, irregularly tetrahedral or pyramidal, attached to a central columella, with a corky testa. Seedling with hypogeal germination; cotyledons not emergent; hypocotyl not elongated; epicotyl bearing scales followed by simple leaves.

Growth is according to Rauh's architectural model, characterized by a monopodial trunk which grows rhythmically and so develops tiers of branches. Each new flush is marked by a few scales followed by pinnate leaves. In India early growth is rapid, over 60 cm in height in 2 months, and an annual diameter increment of 0.8 cm has been recorded. In Thailand a mean annual diameter increment of 1.3 cm was recorded for trees of approximately 10 cm in diameter. On the other hand, in Bangladesh the annual diameter increment of X. moluccensis was very small being 0.2 cm over a 13-year period. Growth characteristics vary greatly between different provenances. Flowering is usually in March-April; fruiting in June-July. Flowers are pollinated by bees. Usually only one fruit is present per inflorescence. The seeds float just below the water surface and are dispersed by ocean currents.

In the past there was much confusion about which name should be applied to which species. There has been complete confusion in the literature making it sometimes impossible to attribute certain data to a given species. The two most common species (X. granatum and X. moluccensis) are easily recognized by their bark features but are difficult to distinguish in the herbarium. X. rumphii can be recognized by its ovate to cordate leaflets.

Growth is according to Rauh's architectural model, characterized by a monopodial trunk which grows rhythmically and so develops tiers of branches. Each new flush is marked by a few scales followed by pinnate leaves. In India early growth is rapid, over 60 cm in height in 2 months, and an annual diameter increment of 0.8 cm has been recorded. In Thailand a mean annual diameter increment of 1.3 cm was recorded for trees of approximately 10 cm in diameter. On the other hand, in Bangladesh the annual diameter increment of X. moluccensis was very small being 0.2 cm over a 13-year period. Growth characteristics vary greatly between different provenances. Flowering is usually in March-April; fruiting in June-July. Flowers are pollinated by bees. Usually only one fruit is present per inflorescence. The seeds float just below the water surface and are dispersed by ocean currents.

In the past there was much confusion about which name should be applied to which species. There has been complete confusion in the literature making it sometimes impossible to attribute certain data to a given species. The two most common species (X. granatum and X. moluccensis) are easily recognized by their bark features but are difficult to distinguish in the herbarium. X. rumphii can be recognized by its ovate to cordate leaflets.

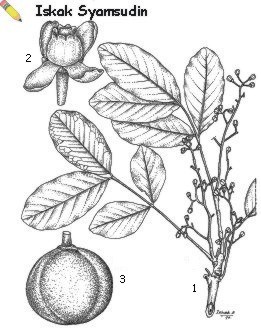

Image

| Xylocarpus granatum J. König – 1, flowering twig; 2, female flower; 3, fruit. |

Ecology

Xylocarpus species are locally common in mangrove swamps, beaches and coastal woodlands on rock, sand and other substrates, generally on locations only flooded at exceptionally high tides. They occur in areas with seasonal climates as well as in those with non-seasonal climates. X. moluccensis is found in the Bruguiera gymnorhiza (L.) Savigny type of mangrove forest. X. granatum is often associated with Nypa and Sonneratia species and may be locally gregarious. X. granatum tolerates a salinity of 0.1-3%. Xylocarpus is a moderate light demander, enduring more shade when young than it does later on. A decrease in freshwater supply during the dry season can result in high mortality.

Silviculture and Management

Xylocarpus may be propagated by seed. Seeds of X. granatum have about 70% germination in 1-2.5 months. Seed viability decreases rapidly upon storage. Seed should to be sown with the convex side upwards. Seedlings can attain 50 cm height in 3 months. Direct sowing has been successfully applied in a trial plantation of X. granatum at 1 m x 1 m. In Aceh (Sumatra) natural regeneration in mangrove forest is good, but X. granatum is cut to allow the more valued Rhizophora spp. to become dominant. It is also reported that roots of X. granatum tend to promote silting up and thus raise the soil level. This, plus the dense crown of X. granatum, hampers the adequate regeneration of Rhizophora. In Peninsular Malaysia Rhizophora and Bruguiera species are considered more valuable in the mangrove forest and Xylocarpus is considered of no economic importance. Large trees are often hollow and it is difficult to obtain large sizes for conversion to timber. Moreover, X. granatum trees are often crooked and gnarled, which further limits their use for sawn timber. X. moluccensis is generally straight-stemmed and reproduces by coppice. Like other Meliaceae of the subfamily Swietenioideae, Xylocarpus is also attacked by Hypsipyla shoot borers. To obtain tannin, the bark is peeled off but the trees recover easily.

Genetic Resources and Breeding

All three Xylocarpus species are comparatively common and widespread and do not seem endangered, except that mangroves are being cleared locally for other uses.

Prospects

Given the desirability of wood of X. moluccensis for high quality furniture and cabinet work, it is worth considering the cultivation of favourable provenances in dry mangrove areas. However, much more needs to be known about its growth and silvicultural aspects. Xylocarpus may also be used increasingly for reforestation and afforestation of coastal wetland.

Literature

[40]All Nippon Checkers Corporation, 1989. Illustrated commercial foreign woods in Japan. Tokyo. 262 pp.

[70]Backer, C.A. & Bakhuizen van den Brink Jr., R.C., 1963-1968. Flora of Java. 3 volumes. Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen.

[124]Bolza, E. & Kloot, N.H., 1963. The mechanical properties of 174 Australian timbers. Technological Paper No 25. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 112 pp.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[162]Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Sabah Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Sabah, Sandakan. xviii + 501 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[300]Eddowes, P.J., 1977. Commercial timbers of Papua New Guinea, their properties and uses. Forest Products Research Centre, Department of Primary Industry, Port Moresby. xiv + 195 pp.

[341]Flora Malesiana (various editors), 1950-. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Boston, London.

[348]Forest Products Research Centre, 1967. Properties and uses of Papua and New Guinea timbers. Forest Products Research Centre, Port Moresby. 30 pp.

[371]Ghosh, S.S., Ramesh Rao, K. & Purkayastha, S.K., 1963. Indian woods: their identification, properties and uses. Vol. 2: Linaceae to Moringaceae. Manager of Publications, Delhi. 386 pp.

[387]Grewal, G.S., 1979. Air-seasoning properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 41. Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 26 pp.

[390]Grijpma, P., 1976. Resistance of Meliaceae against the shoot borer Hypsipyla with particular reference to Toona ciliata M.J. Roem. var. australis (F. v. Muell.) C.DC. In: Burley, J. & Styles, B.T. (Editors): Tropical trees. Variation, breeding and conservation. Linnean Society Symposium Series No 2. Academic Press, London. pp. 69-78.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[464]Ilic, J., 1990. The CSIRO macro key for hardwood identification. CSIRO, Highett. 125 pp.

[526]Kartasujana, I. & Martawijaya, A., 1979. Kayu perdagangan Indonesia - sifat dan kegunaannya [Commercial woods of Indonesia - their properties and uses]. Lembaga Penelitian Hasil Hutan, Bogor. 28 pp.

[536]Keating, W.G. & Bolza, E., 1982. Characteristics, properties and uses of timbers. Vol. 1. South-East Asia, northern Australia and the Pacific. Inkata Press Proprietary Ltd., Melbourne, Sydney & London. 362 pp.

[568]Kingston, R.S.T. & Risdon, C.J.E., 1961. Shrinkage and density of Australian and other South-West Pacific woods. Technological Paper No 13. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 65 pp.

[632]Kraemer, J.H., 1951. Trees of the western Pacific region. Tri-State Offset Company, Cincinnatti. 436 pp.

[663]Latif, M.A., Rahman, M.F., Das, S. & Siddiqi, N.A., 1992. Diameter increments for six mangrove species in the Sundarbans forest of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Forest Science 21: 7-12.

[696]Lemmens, R.H.M.J. & Wulijarni-Soetjipto, N. (Editors), 1991. Plant resources of South-East Asia No 3. Dye and tannin-producing plants. Pudoc, Wageningen. 195 pp.

[732]Macnae, W., 1966. Mangroves in eastern and southern Australia. Australian Journal of Botany 14: 67-104.

[780]Meniado, J.A. et al., 1975-1981. Wood identification handbook for Philippine timbers. 2 volumes. Government Printing Office, Manila. 370 pp. & 186 pp.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[845]Noakes, D.S.P., 1955. Methods of increasing growth and obtaining natural regeneration of the mangrove type in Malaya. Malayan Forester 18: 23-30.

[846]Noamesi, G.K., 1958. A revision of Xylocarpaceae (Meliaceae). PhD Thesis, University of Wisconsisn, Madison. 156 pp.

[878]Pennington, T.D. & Styles, B.T., 1975. A generic monograph of the Meliaceae. Blumea 22: 419-540.

[880]Percival, M. & Womersley, J.S., 1975. Floristics and ecology of the mangrove vegetation of Papua New Guinea. Botany Bulletin No 8. Department of Forests, Division of Botany, Lae. 96 pp.

[933]Research Institute of Wood Industry, 1988. Identification, properties and uses of some Southeast Asian woods. Chinese Academy of Forestry, Wan Shou Shan, Beijing & International Tropical Timber Organization, Yokohama. 201 pp.

[934]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[951]Robillos, Y.U., 1976. Some medicinal forest trees in the Philippines. FORPRIDECOM Technical Note No 169. 3 pp.

[993]Schnepper, W.C.R., 1933. Vloedbosch culturen [Mangrove plantations]. Tectona 27: 299-303.

[1008]Shiokura, T., 1989. A method to measure radial increment in tropical trees. IAWA Bulletin n.s. 10: 147-154.

[1038]Smitinand, T., 1980. Thai plant names. Royal Forest Department, Bangkok. 379 pp.

[1052]Stadelman, R.C., 1966. Forests of Southeast Asia. Princeton, Memphis, Tennessee. 245 pp.

[1056]Steup, F.K.M., 1946. Boschbeheer in de vloedbosschen van Riouw [Forest management in the mangrove forests of Riau]. Tectona 36: 289-298.

[1066]Styles, B.T. & Vosa, C.G., 1971. Chromosome numbers in the Meliaceae. Taxon 20: 485-499.

[1071]Sukardjo, S. & Akhmad, S., 1982. Mangrove forests of Java and Bali. In: Kostermans, A.Y. & Sastroutomo, S.S. (Editors): Proceedings symposium on mangrove forest ecosystem productivity in Southeast Asia. BIOTROP Special Publication No 17. BIOTROP-SEAMEO, Bogor. 226 pp.

[1098]Timber Research and Development Association, 1979. Timbers of the world. Volume 1. Africa, S. America, Southern Asia, S.E. Asia. TRADA/The Construction Press, Lancaster. 463 pp.

[1101]Tomlinson, P.B., 1986. The botany of mangroves. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, London, New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, Sydney. 413 pp.

[1104]Troup, R.S., 1921. Silviculture of Indian trees. 3 volumes. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

[1168]Versteegh, F., 1951. Proeve van een bedrijfsregeling voor de vloedbossen van Bengkalis [Design of a working plan for mangrove forests in Bengkalis]. Tectona 41: 200-258.

[1189]Watson, J.G., 1928. Mangrove forests of the Malay Peninsula. Malayan Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Kuala Lumpur. 275 pp.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1239]Wong, T.M., 1976. Wood structure of the lesser known timbers of Peninsular Malaysia. Malayan Forest Records No 28. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. xi + 115 pp.

[1242]Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 30. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 259 pp.

[70]Backer, C.A. & Bakhuizen van den Brink Jr., R.C., 1963-1968. Flora of Java. 3 volumes. Wolters-Noordhoff, Groningen.

[124]Bolza, E. & Kloot, N.H., 1963. The mechanical properties of 174 Australian timbers. Technological Paper No 25. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 112 pp.

[151]Browne, F.G., 1955. Forest trees of Sarawak and Brunei and their products. Government Printing Office, Kuching, Sarawak. xviii + 369 pp.

[162]Burgess, P.F., 1966. Timbers of Sabah. Sabah Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Sabah, Sandakan. xviii + 501 pp.

[163]Burkill, I.H., 1966. A dictionary of the economic products of the Malay Peninsula. 2nd edition. Ministry of Agriculture and Co-operatives, Kuala Lumpur. Vol. 1 (A-H) pp. 1-1240. Vol. 2 (I-Z) pp. 1241-2444.

[267]Desch, H.E., 1941-1954. Manual of Malayan timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 15. 2 volumes. Malaya Publishing House Ltd., Singapore. 762 pp.

[300]Eddowes, P.J., 1977. Commercial timbers of Papua New Guinea, their properties and uses. Forest Products Research Centre, Department of Primary Industry, Port Moresby. xiv + 195 pp.

[341]Flora Malesiana (various editors), 1950-. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, Boston, London.

[348]Forest Products Research Centre, 1967. Properties and uses of Papua and New Guinea timbers. Forest Products Research Centre, Port Moresby. 30 pp.

[371]Ghosh, S.S., Ramesh Rao, K. & Purkayastha, S.K., 1963. Indian woods: their identification, properties and uses. Vol. 2: Linaceae to Moringaceae. Manager of Publications, Delhi. 386 pp.

[387]Grewal, G.S., 1979. Air-seasoning properties of some Malaysian timbers. Malaysian Forest Service Trade Leaflet No 41. Malaysian Timber Industry Board, Kuala Lumpur. 26 pp.

[390]Grijpma, P., 1976. Resistance of Meliaceae against the shoot borer Hypsipyla with particular reference to Toona ciliata M.J. Roem. var. australis (F. v. Muell.) C.DC. In: Burley, J. & Styles, B.T. (Editors): Tropical trees. Variation, breeding and conservation. Linnean Society Symposium Series No 2. Academic Press, London. pp. 69-78.

[436]Heyne, K., 1927. De nuttige planten van Nederlands-Indië [The useful plants of the Dutch East Indies]. 2nd edition, 3 volumes. Departement van Landbouw, Nijverheid en Handel in Nederlandsch-Indië. 1953 pp. (3rd edition, 1950. van Hoeve, 's-Gravenhage/Bandung. 1660 pp.).

[464]Ilic, J., 1990. The CSIRO macro key for hardwood identification. CSIRO, Highett. 125 pp.

[526]Kartasujana, I. & Martawijaya, A., 1979. Kayu perdagangan Indonesia - sifat dan kegunaannya [Commercial woods of Indonesia - their properties and uses]. Lembaga Penelitian Hasil Hutan, Bogor. 28 pp.

[536]Keating, W.G. & Bolza, E., 1982. Characteristics, properties and uses of timbers. Vol. 1. South-East Asia, northern Australia and the Pacific. Inkata Press Proprietary Ltd., Melbourne, Sydney & London. 362 pp.

[568]Kingston, R.S.T. & Risdon, C.J.E., 1961. Shrinkage and density of Australian and other South-West Pacific woods. Technological Paper No 13. Division of Forest Products, CSIRO, Melbourne. 65 pp.

[632]Kraemer, J.H., 1951. Trees of the western Pacific region. Tri-State Offset Company, Cincinnatti. 436 pp.

[663]Latif, M.A., Rahman, M.F., Das, S. & Siddiqi, N.A., 1992. Diameter increments for six mangrove species in the Sundarbans forest of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Forest Science 21: 7-12.

[696]Lemmens, R.H.M.J. & Wulijarni-Soetjipto, N. (Editors), 1991. Plant resources of South-East Asia No 3. Dye and tannin-producing plants. Pudoc, Wageningen. 195 pp.

[732]Macnae, W., 1966. Mangroves in eastern and southern Australia. Australian Journal of Botany 14: 67-104.

[780]Meniado, J.A. et al., 1975-1981. Wood identification handbook for Philippine timbers. 2 volumes. Government Printing Office, Manila. 370 pp. & 186 pp.

[829]Ng, F.S.P., 1991-1992. Manual of forest fruits, seeds and seedlings. 2 volumes. Malayan Forest Record No 34. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 997 pp.

[831]Ng, F.S.P. & Mat Asri Ngah Sanah, 1991. Germination and seedling records. Research Pamphlet No 108. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 191 pp.

[845]Noakes, D.S.P., 1955. Methods of increasing growth and obtaining natural regeneration of the mangrove type in Malaya. Malayan Forester 18: 23-30.

[846]Noamesi, G.K., 1958. A revision of Xylocarpaceae (Meliaceae). PhD Thesis, University of Wisconsisn, Madison. 156 pp.

[878]Pennington, T.D. & Styles, B.T., 1975. A generic monograph of the Meliaceae. Blumea 22: 419-540.

[880]Percival, M. & Womersley, J.S., 1975. Floristics and ecology of the mangrove vegetation of Papua New Guinea. Botany Bulletin No 8. Department of Forests, Division of Botany, Lae. 96 pp.

[933]Research Institute of Wood Industry, 1988. Identification, properties and uses of some Southeast Asian woods. Chinese Academy of Forestry, Wan Shou Shan, Beijing & International Tropical Timber Organization, Yokohama. 201 pp.

[934]Reyes, L.J., 1938. Philippine woods. Technical Bulletin No 7. Commonwealth of the Philippines, Department of Agriculture and Commerce. Bureau of Printing, Manila. 536 pp. + 88 plates.

[951]Robillos, Y.U., 1976. Some medicinal forest trees in the Philippines. FORPRIDECOM Technical Note No 169. 3 pp.

[993]Schnepper, W.C.R., 1933. Vloedbosch culturen [Mangrove plantations]. Tectona 27: 299-303.

[1008]Shiokura, T., 1989. A method to measure radial increment in tropical trees. IAWA Bulletin n.s. 10: 147-154.

[1038]Smitinand, T., 1980. Thai plant names. Royal Forest Department, Bangkok. 379 pp.

[1052]Stadelman, R.C., 1966. Forests of Southeast Asia. Princeton, Memphis, Tennessee. 245 pp.

[1056]Steup, F.K.M., 1946. Boschbeheer in de vloedbosschen van Riouw [Forest management in the mangrove forests of Riau]. Tectona 36: 289-298.

[1066]Styles, B.T. & Vosa, C.G., 1971. Chromosome numbers in the Meliaceae. Taxon 20: 485-499.

[1071]Sukardjo, S. & Akhmad, S., 1982. Mangrove forests of Java and Bali. In: Kostermans, A.Y. & Sastroutomo, S.S. (Editors): Proceedings symposium on mangrove forest ecosystem productivity in Southeast Asia. BIOTROP Special Publication No 17. BIOTROP-SEAMEO, Bogor. 226 pp.

[1098]Timber Research and Development Association, 1979. Timbers of the world. Volume 1. Africa, S. America, Southern Asia, S.E. Asia. TRADA/The Construction Press, Lancaster. 463 pp.

[1101]Tomlinson, P.B., 1986. The botany of mangroves. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, London, New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, Sydney. 413 pp.

[1104]Troup, R.S., 1921. Silviculture of Indian trees. 3 volumes. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

[1168]Versteegh, F., 1951. Proeve van een bedrijfsregeling voor de vloedbossen van Bengkalis [Design of a working plan for mangrove forests in Bengkalis]. Tectona 41: 200-258.

[1189]Watson, J.G., 1928. Mangrove forests of the Malay Peninsula. Malayan Forest Records No 6. Forest Department, Kuala Lumpur. 275 pp.

[1221]Whitmore, T.C. & Ng, F.S.P. (Editors), 1972-1989. Tree flora of Malaya. A manual for foresters. 4 volumes. Malayan Forest Records No 26. Longman Malaysia Sdn. Berhad, Kuala Lumpur & Petaling Jaya.

[1239]Wong, T.M., 1976. Wood structure of the lesser known timbers of Peninsular Malaysia. Malayan Forest Records No 28. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. xi + 115 pp.

[1242]Wong, T.M., 1982. A dictionary of Malaysian timbers. Malayan Forest Records No 30. Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Kepong. 259 pp.

Author(s)

S. Sukardjo

Xylocarpus granatum

Xylocarpus moluccensis

Xylocarpus rumphii

Xylocarpus moluccensis

Xylocarpus rumphii

Correct Citation of this Article

Sukardjo, S., 1998. Xylocarpus J. König. In: Sosef, M.S.M., Hong, L.T. and Prawirohatmodjo, S. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 5(3): Timber trees; Lesser-known timbers. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

Selection of Species

The following species in this genus are important in this commodity group and are treated separatedly in this database:

Xylocarpus granatum

Xylocarpus moluccensis

Xylocarpus rumphii

Xylocarpus granatum

Xylocarpus moluccensis

Xylocarpus rumphii

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.