Record Number

664

PROSEA Handbook Number

19: Essential-oil plants

Taxon

Jasminum grandiflorum L.

Protologue

Sp. pl., ed. 2: 9 (1762).

Family

OLEACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 26

Synonyms

Jasminum officinale L. var. grandiflorum (L.) Stokes (1830), Jasminum floribundum R. Br. ex Fresen. (1837), Jasminum officinale L. forma grandiflorum (L.) Kobuski (1932).

Vernacular Names

Jasmine, Spanish jasmine, French jasmine (En). Jasmin odorant (Fr). Indonesia: melati gambir (Java). Thailand: cha-khaan, sa thaan (northern). Vietnam: chi-nh[af]i.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

The exact origin of Jasminum grandiflorum is not known; wild populations occur from China, Burma (Myanmar), Nepal and Bhutan through India, Pakistan and Arabia (Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen) to eastern Africa (Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Uganda and Kenya). Arabia and the foothills of the western Himalayas have been mentioned as possible areas for its origin. Jasminum grandiflorum is widely cultivated in warm temperate, subtropical and tropical climates all over the world for its scented flowers, as an ornamental and as a source of oil. There used to be important plantations in France (Grasse), but when labour became expensive, the major areas of cultivation became Algeria, Morocco, Italy (Calabria and Sicily), Spain and Egypt. In India and China, jasmine has been cultivated for local use since antiquity. In South-East Asia Jasminum grandiflorum is mainly cultivated as an ornamental and for its fragrant flowers (e.g. in Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand). It was introduced into Indonesia from Taiwan and has been cultivated there since 1930; since the 1970s it has also been grown as an industrial crop by smallholders.

Uses

In practically all countries in which jasmine occurs its fragrant flowers have been used since antiquity for personal adornment, in religious ceremonies, strewn at feasts and added to baths. Fresh flower production and distribution is a big industry, especially in the Middle East and the Mediterranean, but also in parts of South-East Asia. Jasmine absolute is the major product of Jasminum grandiflorum flowers. It has a powerful and tenacious odour and is common in all kinds of perfumes. The residue of the concrete after extraction of the absolute (e.g. wax) can be used in soaps and is an excellent perfume fixative. Attar of jasmine or East Indian jasmine oil is prepared by water distillion of flowers and collecting the distillate in a base oil e.g. sandalwood oil. Perfumed oils are produced by extracting flowers with hot sesame or groundnut oil or by mixing flowers with boiled sesame seed and subsequently expressing the seed oil. Jasmine absolute and concrete are used as additives in food and tobacco. In China and Indonesia, jasmine flowers are popular to flavour tea. Jasmine oil or essence is used medicinally. It is said to stimulate the reproductive system as an aphrodisiac and as a muscle relaxant, by warming and softening nerves and tendons.

Production and International Trade

In 1994 the United States imported about 10 t jasmine oil valued at about 200 US$ per kg. The export trade in fresh jasmine flowers by air from Bombay to the Middle East and Gulf States totalled 30 t in 1995. Egypt is one of the major suppliers of concrete to the world market. An Indo-French joint venture in Coimbatore processed 500 t flowers in 1995. China consumes much of its production domestically. The area of jasmine cultivation in Central Java was about 580 ha in 1976/1977.

Properties

Jasmine concrete, the major jasmine product traded, is obtained by solvent extraction (using petroleum ether, hexane or liquid carbon dioxide) of fresh flowers. It is normally a yellowish to reddish orange-brown waxy solid, only partially soluble in 95% alcohol with an odour like jasmine absolute. Jasmine absolute is a dark orange-brown viscous liquid, darkening with age to red-brown or even deep red. Its odour is intense floral, warm, rich, highly diffusive, with a peculiar waxy-herbaceous oily-fruity and tea-like undertone. Light may reduce the quality of the absolute, especially degrading the benzyl acetate and benzyl benzoate it contains. The major components from jasmine absolute (Egyptian samples) include: benzyl acetate, benzyl benzoate, isophytol, phytol, phytol acetate, linalool and methyl jamonate. Composition varies due to many factors, e.g. cultivar, time of day the flowers were plucked, flower age, weather conditions, season of plucking, time between plucking and extraction, extraction method and extraction solvent. In the United States, jasmine concrete and absolute are 'generally recognized as safe' (GRAS Nos 2599, 2600 respectively). See also: Composition of essential-oil samples.

Description

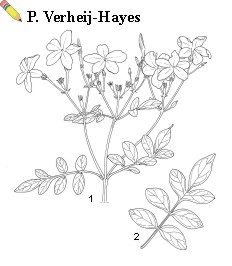

Evergreen or deciduous shrub, often scandent, 2—3(—5) m tall or long; branches stiff, erect, angular, subglabrous to finely pilose. Leaves opposite, imparipinnately compound, glabrous or finely pilose, coriaceous, glossy-green; rachis flattened or winged; petiole 7—10 mm long; leaflets 3—11; petiolule 0—5 mm long; lateral leaflet blade ovate-elliptical, 0.5—3.5 cm x 0.3—2 cm, base rounded to obtuse, margin entire, ciliolate, apex acute to rounded; terminal leaflet ovate-lanceolate, 1—5 cm x 0.4—2.2 cm, base attenuate and decurrent onto the rachis, margin entire, ciliolate, apex acute-acuminate. Inflorescence cymose, 3—many-flowered; flowers very fragrant, 4—5 cm in diameter; pedicel 3—20 mm long, the central cymose pedicels much shorter than the laterals; calyx tubular, tube up to 2 mm long, lobes 5—7, filiform, 3—10 mm long, glabrous; corolla tubular, tube 15—22 mm long, 4—6-lobed, lobes ovate to narrowly lanceolate, 8—17 mm x 4—8 mm, white, usually reddish tinged or streaked outside; stamens 2, filaments 0.5 mm long, attached at about the middle of the corolla tube, anther 5—5.5 mm long, connective a short acute appendage; pistil with 2-locular ovary, style as long as corolla tube or 6 mm long in short-styled flowers, stigma about 4 mm long, slightly 2-grooved. Fruit a 2-lobed berry, lobes ellipsoid, 10 mm x 8 mm, black when ripe.

Image

| Jasminum grandiflorum L. — 1, flowering branch; 2, leaf. |

Growth and Development

Jasminum grandiflorum grows slowly the first 2 years after planting, but first flowering starts at the age of 6 months. In the 3rd and following years flowering is profuse. Jasminum grandiflorum is day-neutral, and floral initiation is promoted by high day and low night temperatures. Mature plants flower for 7—9 months per year in warm regions, 4—6 months in temperate regions. In Europe, Egypt and northern India the main flowering period is usually July—October, in southern India from May to December. Seed set is usually very low and pollen sterility frequently above 75%. Flowers open early in the morning and oil content decreases considerably after 10 a.m. In Europe, flowers contain substantially more essential oil in August and September than in July and October. Jasmine plantations usually remain productive for 10—15 years but perhaps much longer if well-managed.

Other Botanical Information

Jasminum grandiflorum is a complex species with wild and cultivated populations. The cultivated plants can best be classified as a cultivar group, here proposed as cv. group Grandiflorum (synonym: subsp. grandiflorum) with the following distinctive characteristics: leaflets (5—)7—9(—11), lower petiolules 0—1(—1.5) mm long, terminal leaflet (1—)1.5—3.5(—4) cm long. The wild plants have been classified as subsp. floribundum (R. Br. ex Fresen.) P.S. Green and are characterized by: leaflets 3—5(—7), lower petiolules 1—3(—5) mm long, terminal leaflet (1.2—)2.5—3(—5) cm long. Jasminum grandiflorum was long considered to be conspecific with Jasminum officinale L., a native of the Sino-Himalayan region that is an old, popular jasmine widely grown in temperate climates for its fragrant flowers (common or poet's jasmine). It is much hardier than Jasminum grandiflorum for which it has also served as a budding rootstock in temperate climates. Jasminum officinale is best distinguished from Jasminum grandiflorum by its subumbellate inflorescence with all pedicels almost equally long while in Jasminum grandiflorum the inflorescence is cymose and the central pedicels are much shorter than the lateral ones. Confusingly, one of the cultivars of Jasminum officinale is called 'Grandiflorum' (synonym: Jasminum grandiflorum hort.).

In addition to Jasminum grandiflorum, two species — Jasminum auriculatum Vahl and Jasminum sambac (L.) Aiton — are also commercially cultivated for their essential oil. Jasminum auriculatum is widely cultivated in India and Thailand and has simple (unifoliolate) or trifoliolate leaves. Jasminum sambac, also with simple leaves, is the most common cultivated species in India and South-East Asia, where it is a major medicinal plant (it relieves headache, rheumatism and other afflictions of the joints). Its flowers and those of Jasminum multiflorum (Burm.f.) Andrews are also used to flavour tea. Many other species are cultivated on a small scale for their fragrant flowers and as ornamentals. About 50 Jasminum species occur in South-East Asia; they deserve better investigation for their commercial prospects.

In addition to Jasminum grandiflorum, two species — Jasminum auriculatum Vahl and Jasminum sambac (L.) Aiton — are also commercially cultivated for their essential oil. Jasminum auriculatum is widely cultivated in India and Thailand and has simple (unifoliolate) or trifoliolate leaves. Jasminum sambac, also with simple leaves, is the most common cultivated species in India and South-East Asia, where it is a major medicinal plant (it relieves headache, rheumatism and other afflictions of the joints). Its flowers and those of Jasminum multiflorum (Burm.f.) Andrews are also used to flavour tea. Many other species are cultivated on a small scale for their fragrant flowers and as ornamentals. About 50 Jasminum species occur in South-East Asia; they deserve better investigation for their commercial prospects.

Ecology

Jasminum grandiflorum prefers warm sunny conditions and with adequate soil moisture it can withstand short periods of very high temperatures. Growth and flowering are depressed by shade, low daytime temperatures and cool wet conditions. Some cultivars are drought and frost resistant. Jasminum grandiflorum is fairly drought tolerant but flowering is strongly reduced by moisture stress. Plantations are usually below 500 m altitude. Almost any well-drained soil is suitable, but sandy clays or loams (pH 6—8) are preferred. Marshy, waterlogged or very stony soils should be avoided, as should saline soils.

Propagation and planting

Since jasmine is very susceptible to root diseases spread from pathogens residing in soil debris, it is necessary to deep plough and to collect and burn plant residues before planting. Jasmine can be propagated by seed, but seed production is usually low, seed viability is seldom above 50% and seed remains viable for 6 months only. Propagation is normally by cuttings, layering or grafting on a selected rootstock, depending on the cultivar. Cuttings 12—20 cm long should be taken from terminal shoots; treatment with a root stimulator increases the strike rate. Layering in the field is done with one-year-old shoots; a slanting cut is made approximately half-way through the shoot some 50 cm from the end; the cut is buried about 10—15 cm deep with the top remaining aboveground. After about 4—6 months the rooted layers can be separated from the parent plant and transplanted. Cuttings taken from shoot tips have given better results than semi-ripe cuttings. They are usually treated with a fungicide, placed in prepared planting holes and watered. A spacing of 2 m x 1.5—2 m is common, requiring some 4000 cuttings per ha, but much closer planting is also practised (up to 30 000 plants per ha). In southern France Jasminum grandiflorum is grafted on 2—3-year-old rootstocks of Jasminum officinale to give protection against frost. In warmer regions grafting is not needed. Jasmine requires support, ranging from individual stakes and trellises to the post and wire systems used in vineyards. To lower plantation establishment costs it is common to intercrop in the first 2 years, as is done in India. In southern Italy intercropping is done in bergamot orange plantations which start producing after 10—15 years.

Husbandry

After planting, jasmine must be weeded regularly, but care must be taken to prevent root damage. Jasmine responds well to fertilizers which are normally applied manually and hoed-in during weeding. An annual application of 15 kg farmyard manure, 60 g N, 120 g P2O5 and 120 g K2O per plant split into 12 monthly doses is usually sufficient. Where farmyard manure or plant residues are not utilized, NPK 10-15-10 is usually applied at planting, but exact amounts should be determined by soil analysis. Irrigation is important when natural rainfall limits flower production. Annual pruning is necessary to ensure that flowers are within reach of pickers, to provide new growth and to remove dead or diseased shoots. Most growers cut back plants to about half their size after flowering (usually to 90 cm) and sometimes leaves are stripped to reduce disease carry-over. Prunings should preferably be burnt. After jasmine cultivation, crop rotation for several years is necessary before jasmine can be planted again on the same field.

Diseases and Pests

Major root and stem rots in jasmine are caused by Phytophthora spp., Pythium spp. and Fusarium spp. Leaf spots are common on jasmine and may be caused by Alternaria spp., Cercospora spp., Puccinia spp., Septoria spp. and in India by Uromyces hobsoni. Bud rot caused by Botrytis spp. can be extremely damaging in excessively damp or humid conditions. All diseases can be prevented or greatly reduced by burning prunings and plant debris. Jasmine can suffer from many pests, but only few are economically important: the cockchafer Melolontha melolontha in Europe and the Middle East and Cetonia aurata in warmer areas. Cutworms, especially Agrotis spp., damage young plants. Caterpillars that damage foliage in Europe and the Middle East are often Acherontia atropos, in warmer Asia they are particularly the army worm (Spodoptera exempta) and bud worm (S. littoralis). Spider mites (Tetranychus spp.) can cause severe defoliation. Nematodes have often been reported, but the extent of their damage is not known.

Harvesting

Jasmine flowers are picked manually between dawn and 10 a.m., during the hot season in India even between 3—8 a.m. Preferably only half-opened and fresh fully opened flowers must be picked, not buds or old (yellowish) flowers, as these will depress the quality of the absolute. Although rain makes flowers almost useless, picking flowers in the rain should continue, to promote further flowering. An experienced picker can harvest 0.5 kg flowers per hour, but the pickers are usually young women and children, who achieve 2 kg in 5 hours.

Yield

Annual flower yield of jasmine varies from 5.5—12.5 t/ha, on average 5—8 t/ha. Modern commercial plantations average 8—10 t/ha. In Java, production is highest during the rainy season (30 kg/ha per day), and lowest during the dry season (4 kg/ha per day). Concrete yield is about 0.1%; up to 0.3% is reported from India. As an approximate guide, 1000 kg flowers yield 1 kg concrete when solvent extracted, half of this as absolute. The annual average flower yield for Jasminum auriculatum in India ranges from 2—9 t/ha, with average concrete yield of 0.3—0.4%. The average annual flower yield for Jasminum sambac is 1—7 t/ha and the concrete yield is 0.1—0.2%.

Handling After Harvest

Jasmine flowers must be quickly processed, since delay substantially reduces essential oil content. Flowers should be kept shaded and cool between picking and processing and the processing facility should be close to the plantation. Freshly picked flowers can be stored in polythene bags at —15°C without loss of yield, quality or odour. Jasmine oil can be obtained from flowers by steam distillation but the yield is very low. Jasmine concrete is obtained from flowers, formerly by enfleurage, currently by solvent extraction. In solvent extraction, flowers are washed up to 3 times with petroleum ether or, preferably, with hydrocarbon-free food-grade hexane; the extract is then distilled to remove the solvent, resulting in the concrete. Concrete is usually produced at the plantation, but absolute is produced where convenient, often in another country.

Genetic Resources

No substantial germplasm collections of Jasminum species are known of. In the countries with commercial jasmine plantations (e.g. India, Egypt, France, Italy, Thailand, the Philippines, Taiwan) working collections are available for breeding but statistics are lacking. In India germplasm of 13 cultivars is present in the Indian Institute of Horticultural Research, Bangalore and at the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, Coimbatore.

Breeding

Variability in jasmines is limited within the Grandiflorum cv. group. There are triploid and tetraploid forms as well as diploid forms. The usual poor seed production is due to abnormal meiosis, cytomixis, defective gene functions and persistent tapetal cells; however, abundant seed-producing clones exist as well. Prospects for breeding, e.g. for disease resistance and higher flower and oil yields seem bright, because variability is large in wild forms of Jasminum grandiflorum and there are many other Jasminum species. Breeding programmes are in progress in all countries with commercial jasmine plantations, particularly in India.

Prospects

Jasmine is interesting in many ways: for its essential oil, as an ornamental, for its fragrant fresh flowers for which there is a considerable market, and for its medicinal properties. The major cultivated species in South-East Asia is Jasminum sambac, but it seems worthwhile to investigate the commercial prospects of producing Jasminum grandiflorum and other Jasminum species as well.

Literature

Green, P.S., 1965. Studies in the genus Jasminum 3. The species in cultivation in North America. Baileya 13: 137—172.

Green, P.S., 1986. Jasminum in Arabia. Studies in the genus Jasminum L. (Oleaceae) 10. Kew Bulletin 41: 413—418.

Green, P.S., 1997. A revision of the pinnate-leaved species of Jasminum. Studies in the genus Jasminum (Oleaceae) 15. Kew Bulletin 52: 933—947.

Guenther, E., 1952. The essential oils. Vol. 5. Concrete and absolute of jasmine. D. van Nostrand Company, New York, United States. pp. 319—338.

Musalam, Y., Kobayashi, A. & Yamanishi, T., 1988. Aroma of Indonesian jasmine tea. In: Lawrence, B.M., Mookherjee, B.D. & Willis, B.J. (Editors): Flavors and fragrances: a world perspective. Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of Essential Oils, Fragrances and Flavours, Washington, DC, United States, 16—20 November 1986. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands. pp. 659—668.

Srivastava, H.C., 1995. French jasmine. In: Chadha, K.L. & Rajendra Gupta (Editors): Advances in horticulture. Vol. 11. Medicinal and aromatic plants. Malhotra Publishing House, New Delhi, India. pp. 805—823.

Tobroni, M., 1981. Tanaman melati di Jawa Tengah dan Yogyakarta [Jasminum cultivation in Central Java and Yogyakarta]. Warta BPTK 7 (3/4): 343—353.

Weiss, E.A., 1997. Essential oil crops. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom. pp. 342—361.

Green, P.S., 1986. Jasminum in Arabia. Studies in the genus Jasminum L. (Oleaceae) 10. Kew Bulletin 41: 413—418.

Green, P.S., 1997. A revision of the pinnate-leaved species of Jasminum. Studies in the genus Jasminum (Oleaceae) 15. Kew Bulletin 52: 933—947.

Guenther, E., 1952. The essential oils. Vol. 5. Concrete and absolute of jasmine. D. van Nostrand Company, New York, United States. pp. 319—338.

Musalam, Y., Kobayashi, A. & Yamanishi, T., 1988. Aroma of Indonesian jasmine tea. In: Lawrence, B.M., Mookherjee, B.D. & Willis, B.J. (Editors): Flavors and fragrances: a world perspective. Proceedings of the 10th International Congress of Essential Oils, Fragrances and Flavours, Washington, DC, United States, 16—20 November 1986. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam, the Netherlands. pp. 659—668.

Srivastava, H.C., 1995. French jasmine. In: Chadha, K.L. & Rajendra Gupta (Editors): Advances in horticulture. Vol. 11. Medicinal and aromatic plants. Malhotra Publishing House, New Delhi, India. pp. 805—823.

Tobroni, M., 1981. Tanaman melati di Jawa Tengah dan Yogyakarta [Jasminum cultivation in Central Java and Yogyakarta]. Warta BPTK 7 (3/4): 343—353.

Weiss, E.A., 1997. Essential oil crops. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom. pp. 342—361.

Author(s)

P.C.M. Jansen

Correct Citation of this Article

Jansen, P.C.M., 1999. Jasminum grandiflorum L.. In: L.P.A. Oyen and Nguyen Xuan Dung (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 19: Essential-oil plants. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.