Record Number

78

PROSEA Handbook Number

19: Essential-oil plants

Taxon

Citrus aurantium L. cv. group Bouquetier

Protologue

Sp. pl.: 782 (1753); cultivar group name is proposed here.

Family

RUTACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 18

Synonyms

Citrus bigaradia Risso & Poiteau (1818), Citrus amara Link (1831), Citrus aurantium L. subsp. amara (Link) Engler (1897).

Vernacular Names

Bouquetier (En). Bouquetier (Fr). For Citrus aurantium in general: Sour orange, bitter orange, Seville orange, bigarade (En). Bigaradier, orange amère (Fr). Indonesia: lemon itam (Moluccas). Malaysia: limau samar. Philippines: cabiso. Burma (Myanmar): kabala, leinmaw. Cambodia: krôôch loviing, léang sat. Thailand: som. Vietnam: b[oor]ng, d[aj]i d[aj]i hoa.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Citrus aurantium most probably originated in north-eastern India and adjoining areas of Burma (Myanmar) and China. It spread north-eastward to Japan and westward through India to the Middle East and from there to Europe, where it rapidly became established in the Mediterranean some 1000 years ago. It became especially common in Spain, hence its vernacular name Seville orange. It was one of the first citrus taken to South America in the 16th Century, where it soon escaped from cultivation and naturalized in many areas. It is now cultivated in many tropical and subtropical countries, but only rarely in South-East Asia. Citrus aurantium has been grown in France since the early 1400s, initially mainly as an ornamental. Later on special perfumery cultivars grown for their fragrant flowers were developed in the French Riviera region and became known as 'Bouquetiers'.

Uses

The flowers of several citrus species yield essential oil called 'neroli oil' in the perfume trade. The flower oil of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck) is called 'neroli Portugal', that of lemon (Citrus limon (L.) Burm.f.) 'neroli citronier'. Flowers of Citrus aurantium yield an essential oil called 'neroli bigarade oil'. The best quality is obtained from Bouquetier cultivars formerly from southern France and Italy and nowadays from Morocco and Tunisia. Neroli oil is a component of high quality perfumes and of the toilet water 'eau-de-Cologne'. Significant amounts (up to 25%) of aroma compounds remain in solution in the water left in the still after distillation of Citrus aurantium flowers. The oil obtained by extraction of these compounds is traded as 'orange flower water absolute' and is mainly used in the reconstitution of other essential oils and of the formerly popular 'orange flower water'. Neroli bigarade oil is sometimes used as a flavour component in food products, including alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages, especially in tea.

'Petitgrain oil' is produced by distilling the leaves and green twigs of several citrus species; those of Citrus aurantium, including the Bouquetiers, yield 'petitgrain bigarade oil'. Petitgrain oils are often used as a substitute for the much more costly neroli oils. Petitgrain water absolute or 'eau-de-brouts' is the equivalent of orange flower water absolute and is obtained as a by-product from petitgrain bigarade oil. It enhances the 'naturalness' of several other fragrances, e.g. jasmine, neroli, ylang- ylang and gardenia. Petitgrain bigarade oil is used as a flavouring in food products, including alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages.

The peel of the fruits of Citrus aurantium is used extensively in the manufacture of citrus marmalade. It also yields the essential oil 'bitter orange oil' (also called 'bitter orange peel oil') mainly used as a flavouring, such as 'orange sec' and 'triple sec' liqueur flavours, and to modify or strengthen the flavour of sweet-orange soft drinks. The average maximum concentration used in food products and drinks is about 0.04%. The sour fruit juice can be used like vinegar. The wood of sour orange is strong and takes a fine polish; it is sometimes used to make furniture.

Citrus aurantium has been used extensively as a rootstock for other citrus species (particularly sweet orange, lemon and grapefruit) because it produces a well-developed root system and has a high degree of resistance to many important diseases (e.g. gummosis, root rot) and to cold. Its popularity as a rootstock has decreased, however, because of its susceptibility to the viral disease tristeza.

Citrus aurantium has several medicinal uses, e.g. in the Caribbean against gall bladder problems; in the Philippines as a stimulant and against ringworm and as an antiseptic against Staphylococcus aureus. Bitter orange peel oil has stomachic, carminative and laxative properties. Dried bitter orange peel is used as tonic and carminative in treating dyspepsia. Preparations from unripe and nearly ripe fruits are used against stomach pains and indigestion in North Africa and China, and against colds and influenza in the Bahamas and China. In aromatherapy neroli bigarade oil is primarily a relaxing oil, but is also applied for its antiseptic, antispasmodic and carminative effect. Because of its sedative effect its use is incompatible with driving.

'Petitgrain oil' is produced by distilling the leaves and green twigs of several citrus species; those of Citrus aurantium, including the Bouquetiers, yield 'petitgrain bigarade oil'. Petitgrain oils are often used as a substitute for the much more costly neroli oils. Petitgrain water absolute or 'eau-de-brouts' is the equivalent of orange flower water absolute and is obtained as a by-product from petitgrain bigarade oil. It enhances the 'naturalness' of several other fragrances, e.g. jasmine, neroli, ylang- ylang and gardenia. Petitgrain bigarade oil is used as a flavouring in food products, including alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages.

The peel of the fruits of Citrus aurantium is used extensively in the manufacture of citrus marmalade. It also yields the essential oil 'bitter orange oil' (also called 'bitter orange peel oil') mainly used as a flavouring, such as 'orange sec' and 'triple sec' liqueur flavours, and to modify or strengthen the flavour of sweet-orange soft drinks. The average maximum concentration used in food products and drinks is about 0.04%. The sour fruit juice can be used like vinegar. The wood of sour orange is strong and takes a fine polish; it is sometimes used to make furniture.

Citrus aurantium has been used extensively as a rootstock for other citrus species (particularly sweet orange, lemon and grapefruit) because it produces a well-developed root system and has a high degree of resistance to many important diseases (e.g. gummosis, root rot) and to cold. Its popularity as a rootstock has decreased, however, because of its susceptibility to the viral disease tristeza.

Citrus aurantium has several medicinal uses, e.g. in the Caribbean against gall bladder problems; in the Philippines as a stimulant and against ringworm and as an antiseptic against Staphylococcus aureus. Bitter orange peel oil has stomachic, carminative and laxative properties. Dried bitter orange peel is used as tonic and carminative in treating dyspepsia. Preparations from unripe and nearly ripe fruits are used against stomach pains and indigestion in North Africa and China, and against colds and influenza in the Bahamas and China. In aromatherapy neroli bigarade oil is primarily a relaxing oil, but is also applied for its antiseptic, antispasmodic and carminative effect. Because of its sedative effect its use is incompatible with driving.

Production and International Trade

In trade statistics a distinction is rarely made between petitgrain and neroli oil from different citrus sources. The total annual world production of petitgrain oil in 1985-1988 was valued at US$ 5.4 million, that of neroli oil at US$ 3.75 million. The annual world production of bitter orange peel oil was valued at US$ 1.1 million (major producers are Jamaica, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Brazil and Italy). Besides France and Italy, the cultivation of Citrus aurantium is most important in Paraguay (especially for petitgrain oil), Morocco and Spain.

Properties

On water distillation, 1 kg of Bouquetier flowers yield about 1 g neroli bigarade oil and about 0.7 l orange flower water. Neroli bigarade oil is a pale yellow, mobile oil becoming darker and more viscous on ageing. Its fragrance characteristics are a light, floral, pleasantly bitter top note, a floral, herbal, green body and a floral, orange flower dry-out lasting about 18 hours. The major chemical components of neroli bigarade oil are: linalool, limonene, linalyl acetate, nerolidol, geraniol, and methyl anthranilate. Extraction of flowers with supercritical CO yields a neroli bigarade oil much richer in linalyl acetate (23%) than neroli oil obtained by water distillation. The content of methyl anthranilate (1%) is also significantly higher. The olfactive and physical characteristics of neroli bigarade oils from the Mediterranean countries are very similar, but neroli bigarade oil from Haiti has a different odour and a distincly higher optical rotation (18-27°). The odour intensity of the CO extract is about twice that of water-distilled oils. Orange flower water absolute, prepared by extracting orange flower water several times with highly rectified petroleum ether, is a yellowish to orange-yellow or pale brownish oil which discolours significantly on ageing. It has a dry floral, musty herbaceous odour, reminiscent of mandarin leaf oil, petitgrain oil and slightly of orange flower absolute. Some sources describe it as having a fresh floral orange flower top note, a rich and heavy floral body with orange flower and animal notes and a floral, heavy, green, animalic dry-out lasting about 24 hours.

As neroli bigarade oil and orange flower water both contain only some of the aromatic components of the flowers, attempts have been made to obtain a more representative extract. Combining neroli bigarade oil and orange flower water absolute does not give the desired result. Extraction of flowers with petroleum ether and then extraction of the resulting concrete with alcohol yields orange flower absolute, a dark brown or orange-coloured viscous liquid with a very intensely floral, heavy and rich, warm, but also delicate and fresh, long-lasting odour, closely resembling the fragrance of fresh bitter orange blossoms. Its fragrance is not unlike that of jasmine, less intensely floral, but with a greater freshness. It is used in many perfumes and flavourings and combines well with a wide range of natural and artificial aroma products.

Petitgrain bigarade oil (also called bitter orange petitgrain oil) is obtained by steam distillation of the leaves and green twigs of Citrus aurantium. It is a pale yellow to amber, mobile liquid with a fresh, floral, orange flower top note, a bitter, floral, herbal and woody body and a dry herbal dry-out lasting about 36 hours.

The main chemical compounds constituting petitgrain bigarade oil are linalool, linalyl acetate and the monoterpene aldehydes geranial and citronellal. Analysis of an oil from China indicated a very similar composition, but a higher proportion of linalool derivatives.

Bitter orange peel oil is obtained by cold expression of the fruit peel of Citrus aurantium. It is only rarely made from Bouquetier cultivars. It is a dark-yellow to olive-yellow or pale-brownish-yellow, mobile liquid with a very characteristic fresh, yet bitter or dry taste, and a lasting, sweet undertone. It consists mainly of limonene (94%), with small quantities of myrcene (2%).

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States has approved for food use and given 'generally recognized as safe' status to neroli bigarade oil, petitgrain bigarade oil and bitter orange peel oil respectively by the GRAS Nos 2771, 2855 and 2823. The Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM) has published monographs on those 3 oils and the International Fragrance Association (IFRA) has issued restrictions relating to the concentrations permitted. In the European Union the oils have been registered under No 136n. See also: Composition of essential-oil samples and the Table on standard physical properties.

As neroli bigarade oil and orange flower water both contain only some of the aromatic components of the flowers, attempts have been made to obtain a more representative extract. Combining neroli bigarade oil and orange flower water absolute does not give the desired result. Extraction of flowers with petroleum ether and then extraction of the resulting concrete with alcohol yields orange flower absolute, a dark brown or orange-coloured viscous liquid with a very intensely floral, heavy and rich, warm, but also delicate and fresh, long-lasting odour, closely resembling the fragrance of fresh bitter orange blossoms. Its fragrance is not unlike that of jasmine, less intensely floral, but with a greater freshness. It is used in many perfumes and flavourings and combines well with a wide range of natural and artificial aroma products.

Petitgrain bigarade oil (also called bitter orange petitgrain oil) is obtained by steam distillation of the leaves and green twigs of Citrus aurantium. It is a pale yellow to amber, mobile liquid with a fresh, floral, orange flower top note, a bitter, floral, herbal and woody body and a dry herbal dry-out lasting about 36 hours.

The main chemical compounds constituting petitgrain bigarade oil are linalool, linalyl acetate and the monoterpene aldehydes geranial and citronellal. Analysis of an oil from China indicated a very similar composition, but a higher proportion of linalool derivatives.

Bitter orange peel oil is obtained by cold expression of the fruit peel of Citrus aurantium. It is only rarely made from Bouquetier cultivars. It is a dark-yellow to olive-yellow or pale-brownish-yellow, mobile liquid with a very characteristic fresh, yet bitter or dry taste, and a lasting, sweet undertone. It consists mainly of limonene (94%), with small quantities of myrcene (2%).

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States has approved for food use and given 'generally recognized as safe' status to neroli bigarade oil, petitgrain bigarade oil and bitter orange peel oil respectively by the GRAS Nos 2771, 2855 and 2823. The Research Institute for Fragrance Materials (RIFM) has published monographs on those 3 oils and the International Fragrance Association (IFRA) has issued restrictions relating to the concentrations permitted. In the European Union the oils have been registered under No 136n. See also: Composition of essential-oil samples and the Table on standard physical properties.

Adulterations and Substitutes

In Paraguay, Citrus aurantium occurs naturalized and is very common. It has been assumed that it is a hybrid with sweet orange, or a mutation and has been classified as "Bittersweet orange"". It is the main source of Paraguayan Citrus aurantium essential oils. These oils differ markedly in fragrance and composition from Bouquetier and other Citrus aurantium oils. Neroli oil from Haiti is obtained by steam distillation of a mixture of flowers of Citrus aurantium and other Citrus species, mainly Citurs maxima (Burm.) Merrill.

Description

Tree, 3-10 m tall, much branched with a rounded crown. Young twigs angled and bearing slender short spines, older branches with stout spines up to 8 cm long. Leaves simple, alternate, subcoriaceous, dotted with glands, aromatic when bruised; petiole 2-3 cm long, upper half narrowly to broadly winged, wing triangular-obovate, up to 2.5 cm wide; blade broadly ovate to elliptical, 7-12 cm x 4-7 cm, base cuneate or obtuse, margin subentire to slightly crenulate, apex obtuse to bluntly pointed. Flowers axillary, single or in a fascicle of 2-3, very fragrant, white, usually bisexual but 5-12% male flowers occur; calyx cupular, 4-5 mm long, 3-5-lobed, lobes broadly ovate-triangular, glabrous to pubescent; petals 4-5, oblong, 1.5 cm x 4 mm; stamens 20-25, often in 4-5 groups, filaments 6-10 mm long, anthers oblong; pistil with glabrous ovary, stout style and capitate stigma. Fruit a depressed-globose hesperidium, 5-8 cm in diameter, with 8-12 segments, central core usually hollow, peel thick, smooth to warty, yellow-orange, strongly aromatic, pulp very acid and slightly bitter. Seeds numerous, polyembryonic, with a high number of nucellar embryos.

Bouquetier cultivars are small, subspineless trees, flowering profusely with very large single flowers.

Bouquetier cultivars are small, subspineless trees, flowering profusely with very large single flowers.

Image

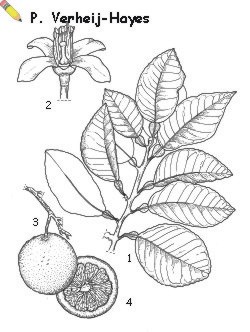

| Citrus aurantium L. — 1, leafy shoot; 2, flower in longitudinal section; 3, fruit; 4, fruit in transverse section. |

Growth and Development

Flowering of Citrus aurantium is strongly influenced by weather conditions. Bright, sunny and dry weather with mild temperatures is most suitable for flower production and harvesting. Cloudy, misty or hot and humid conditions reduce flower numbers and oil content. In France and most of the Mediterranean flowering occurs in late spring (May-June). Bitter orange has a long life span; orchards 80-100 years old can still be productive.

Other Botanical Information

The taxonomy of Citrus aurantium as species and at sub-specific level is very confused and in dire need of revision, as is the taxonomy of the entire genus Citrus L. It is possible that Citrus aurantium originated as a hybrid between the mandarin (Citrus reticulata Blanco) and the pummelo (Citrus maxima (Burm.) Merrill), which perpetuates chiefly apomictically. In Europe, sour orange was known long before the sweet orange, and for a long time sweet orange has been considered as a variety of sour orange. Now sweet orange (Citrus sinensis) is considered as a completely different species (main differences: sour orange has longer and broader winged petioles, leaf blades are narrower and more pointed, fruits are brighter orange and have a rougher peel and oil glands are sunken in the peel). Cultivars grown for the production of essential oils are often referred to as Citrus aurantium L. subsp. amara Engl., but a cultivar group classification is more appropriate for cultivated plants. Bouquetiers are a small group of cultivars grown mainly in France for the perfume industry. Some well known cultivars are: 'Bouquetier à Grandes Fleurs' (the most important perfume cultivar; synonym: 'Bouquetier à Peau Epaisse'), 'Bigaradier de Grasse', 'Bouquetier à Fruits Dur', 'Bouquetier à Fruits Mous', 'Bouquetier de Nice à Fleurs Double' (cultivar with double flowers; synonyms: 'Bouquetier de Nice à Fruits Plats', 'Bouquetier de Nice') and 'Bouquet' (a cultivar very well suited as ornamental hedge plant; synonym: 'Bouquet de Fleurs').

Ecology

Citrus aurantium, including the Bouquetier cultivars, requires a warm climate with an optimum average annual temperature of 22-24°C, but temperatures of up to 45°C are tolerated, provided soil moisture is adequate. Plantations are mostly located below 500 m altitude and perform best up to 300 m. Cold weather may cause damage, especially to trees weakened by diseases or pests. Frost causes serious damage and a few days with minimum temperatures of -4°C may kill the young, non-lignified branches, while severe frost or icing is often fatal. In some years, late spring frosts destroy a great part of the flowers in France and other Mediterranean countries. Growth and flowering are optimal under sunny conditions. Annual rainfall of 1000 mm falling mainly in spring and summer is the optimum, and irrigation is required where annual rainfall is below 750 mm. Very strong winds may cause tree damage, while dry hot winds in spring may reduce leaf size and number and cause extensive withering during flowering. If the climate is favourable, Citrus aurantium can be planted in almost any kind of soil that is not compacted, wet for long periods or contains excessive amounts of clay, lime or silica.

Propagation and planting

Like other bitter oranges, Bouquetiers are propagated by seed or grafting. In France, seed is planted in seedbeds in spring and seedlings are transplanted into a nursery after 2 years at a spacing of 1 m x 30 cm. When planted out in the field, the spacing is 4 m x 4-5 m, but the spacing between rows may be reduced to 1-1.5 m if all cultivation is manual. Grafting is usually performed at the beginning of summer, when the bark of the rootstock can be loosened easily from the wood.

Husbandry

During the first year after planting out, sour orange must be pruned to keep the foliage off the ground. Weed control is essential until the young plants are well established and growing vigorously. In France, the ground between trees is cultivated several times per year when applying fertilizer: in spring, twice during summer and after application of manure in September-October. In many other locations fertilizer is seldom used. Trees are commonly mulched with spent material from stills. Irrigation is applied when necessary and is particularly important during the first years after transplanting. Pruning to keep an open crown is done after the harvest of the flowers. The leaf material removed may be used to distill petitgrain bigarade. When prices are low, orchards are often neglected for long periods. When prices recover, trees can be coppiced without harm and resume normal growth and production.

Diseases and Pests

The principal disease of bitter orange in France is sooty mould. It often follows aphid attack and is caused by fungi living on honeydew and covering the leaves with a black dust, thus impeding their functioning. Citrus aurantium is resistant to gummosis, caused by Phytophthora spp., but susceptible to scab, caused by Elsinoe fawcetti, and intolerant of the tristeza virus. Scale insects are the main pests in the Mediterranean region.

Harvesting

The first harvest of flowers and leaves of bitter orange takes place 3-4 years after planting in the field. Seedling trees are then cut back to 12-15 cm above the ground. Flowers are picked by hand when they are just open, as early in the morning as possible for the best quality oil. Unopened buds and wilted flowers impart a grassy odour to the oil, leaves impart an off-note. Flowers are kept overnight, spread out in a thin layer, and brought to the still early the next morning.

Leaves are harvested annually or, in the tropics, even at 9-month intervals. Where flowers are harvested, pruning is done afterwards, i.e. in July-October in France. In Haiti trees are pruned throughout the year. All prunings are transported to the still, where leaves and twigs are stripped, and larger branches are used as fuel.

In southern Italy and Spain, where bitter orange is often grown for its fruit, harvesting is done in January-February, sometimes up to March.

Leaves are harvested annually or, in the tropics, even at 9-month intervals. Where flowers are harvested, pruning is done afterwards, i.e. in July-October in France. In Haiti trees are pruned throughout the year. All prunings are transported to the still, where leaves and twigs are stripped, and larger branches are used as fuel.

In southern Italy and Spain, where bitter orange is often grown for its fruit, harvesting is done in January-February, sometimes up to March.

Yield

Flower yields of bitter orange increase until trees are about 20 years old. A 10-year-old tree may yield about 6 kg of flowers per year, a full-grown tree up to 20 kg. The average annual yield per tree is somewhat higher in North Africa than in France, where trees are kept smaller. About 1 g neroli oil can be obtained from 1 kg flowers. The oil content of the leaves increases as temperatures rise (from April-June in Italy). The yield of leaves depends on the management of the trees. Leaves from trees exposed to sunlight generally have a higher oil content than those from shaded trees, and distilling fresh leaves gives the highest yields. In Haiti, leaves can be harvested throughout the year, but the best quality oil is obtained in May-October after the flower harvest. In Paraguay, annual leaf oil yields increase steadily until the 5th year, after which they remain constant for decades under good management. In Paraguay, individual trees may produce 10-15 kg leaves annually, while 200-300 kg leaves about 1 kg oil. In Haiti 300-400 kg leaves yield about 1 kg oil; in France 500 kg are needed for 1 kg oil.

Handling After Harvest

Neroli oil is extracted from the flowers of bitter orange by water distillation. Treating the flowers with steam would cause them to clump together, so instead they are put directly in the water in the still, which is then heated indirectly. In modern stills in France, 250-300 kg of flowers are distilled in 200-250 l of water. About 15% of the water containing about 75% of the volatile compounds is distilled over, yielding neroli oil by separation. About 25% of the aroma compounds remain dissolved in the water; they are recovered by solvent extraction, yielding orange flower water. On average, distillation of 1 kg flowers yields 1 g neroli bigarade oil plus 0.7 l of orange flower water and takes about 3 hours. Some producers prefer a more concentrated product and use a higher proportion of flowers to water.

Petitgrain bigarade oil is obtained by steam distillation of the leaves and green twigs. Care should be taken to remove all wood, young fruits and prunings of other citrus species.

Bitter orange oil is expressed from the peel of the fruit by hand or machine. In southern Italy the old 'sponge' method of extraction has long been used, as this allowed the subsequent use of the peel in marmalade manufacturing.

Petitgrain bigarade oil is obtained by steam distillation of the leaves and green twigs. Care should be taken to remove all wood, young fruits and prunings of other citrus species.

Bitter orange oil is expressed from the peel of the fruit by hand or machine. In southern Italy the old 'sponge' method of extraction has long been used, as this allowed the subsequent use of the peel in marmalade manufacturing.

Genetic Resources

A collection of 39 accessions of Citrus aurantium cultivars including Bouquetiers is maintained by the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique in St. Ghjulianu, Corsica, France, while the National Germplasm Repository in Riverside, the United States holds 45 accessions. Most other Mediterranean countries and several countries in South America also hold collections of Citrus aurantium germplasm.

Breeding

No current breeding programmes are known to exist.

Prospects

The importance of the various essential oils obtained from Citrus aurantium for the production of high quality perfumes and their excellent qualities for the improvement of the odour of other aroma materials guarantee the continued interest in this crop. This applies especially to the Bouquetiers, as they provide oil of the best quality. The wide adaptibility of Citrus aurantium indicated by its wide area of distribution and production justifies trialling it in South-East Asia.

Literature

Boelens, M.H., 1991. A critical review on the chemical composition of the Citrus oils. Perfumer & Flavorist 16: 17-34.

Boelens, M.H. & Jimenez, R., 1989. The chemical composition of the peel oils from unripe and ripe fruits of bitter orange, Citrus aurantium L. ssp. amara Engl. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 4: 139-142.

Boelens, M.H. & Oporto, A., 1991. Natural isolates from Seville bitter orange tree. Perfumer & Flavorist 16: 1-7.

Guenther, E., 1949. The essential oils. Vol. 3. Van Nostrand, New York, United States. pp. 197-260.

Hodgson, R.W., 1967. Horticultural varieties of Citrus. In: Reuther, W., Webber, H.J. & Batchelor, L.D. (Editors): The citrus industry. Vol. 1. History, world distribution, botany, and varieties. Revised Edition. University of California, United States. pp. 489-496.

Lin Zheng-kui, Kua Ying-fang & Gu Yu-hong, 1986. The chemical constituents of the essential oil from the flowers, leaves and peels of Citrus aurantium. Acta Botanica Sinica 28: 635-640.

Mondello, L.M., Dugo, G., Dugo, P. & Bartle, K.D., 1996. Italian Citrus petitgrain oils. Part 1. Composition of bitter orange petitgrain oil. Journal of Essential Oil Research 8: 597-609.

Swingle, W.T. & Reece, P.C., 1967. The botany of Citrus and its wild relatives. In: Reuther, W., Webber, H.J. & Batchelor, L.D. (Editors): The citrus industry. Vol. 1. History, world distribution, botany, and varieties. Revised Edition. University of California, United States. pp. 374-379.

Weiss, E.A., 1997. Essential oil crops. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom. pp. 444-459.

Boelens, M.H. & Jimenez, R., 1989. The chemical composition of the peel oils from unripe and ripe fruits of bitter orange, Citrus aurantium L. ssp. amara Engl. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 4: 139-142.

Boelens, M.H. & Oporto, A., 1991. Natural isolates from Seville bitter orange tree. Perfumer & Flavorist 16: 1-7.

Guenther, E., 1949. The essential oils. Vol. 3. Van Nostrand, New York, United States. pp. 197-260.

Hodgson, R.W., 1967. Horticultural varieties of Citrus. In: Reuther, W., Webber, H.J. & Batchelor, L.D. (Editors): The citrus industry. Vol. 1. History, world distribution, botany, and varieties. Revised Edition. University of California, United States. pp. 489-496.

Lin Zheng-kui, Kua Ying-fang & Gu Yu-hong, 1986. The chemical constituents of the essential oil from the flowers, leaves and peels of Citrus aurantium. Acta Botanica Sinica 28: 635-640.

Mondello, L.M., Dugo, G., Dugo, P. & Bartle, K.D., 1996. Italian Citrus petitgrain oils. Part 1. Composition of bitter orange petitgrain oil. Journal of Essential Oil Research 8: 597-609.

Swingle, W.T. & Reece, P.C., 1967. The botany of Citrus and its wild relatives. In: Reuther, W., Webber, H.J. & Batchelor, L.D. (Editors): The citrus industry. Vol. 1. History, world distribution, botany, and varieties. Revised Edition. University of California, United States. pp. 374-379.

Weiss, E.A., 1997. Essential oil crops. CAB International, Wallingford, United Kingdom. pp. 444-459.

Author(s)

L.P.A. Oyen & P.C.M. Jansen

Correct Citation of this Article

Oyen, L.P.A. & Jansen, P.C.M., 1999. Citrus aurantium L. cv. group Bouquetier. In: L.P.A. Oyen and Nguyen Xuan Dung (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 19: Essential-oil plants. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.