Record Number

840

PROSEA Handbook Number

14: Vegetable oils and fats

Taxon

Simmondsia chinensis (Link) C.K. Schneider

Protologue

Ill. Handb. der Laubholzk. 2: 141 (1907).

Family

SIMMONDSIACEAE

Chromosome Numbers

2n = 52

Synonyms

Buxus chinensis Link (1822), Simmondsia californica Nuttall. (1844).

Vernacular Names

Jojoba, goat nut (En). Jojoba (Fr). Indonesia: jojoba. Philippines: jojoba. Thailand: jojoba.

Origin and Geographic Distribution

Jojoba is native to the Sonora semi-desert in north-western Mexico and the south-western United States, but is thought to have originated near the Pacific coast in the Baja California peninsula, where the climate is milder and more even. The similarity of its oil to sperm whale oil was first discovered in 1933, and the later ban on the import of sperm whale oil into the United States in 1969 gave a big impetus to its development as an oil crop and its distribution outside its native habitat. Since the 1980s, its commercial production has spread to South and Central America, southern Africa, Australia and the Middle East. Experimental plantations have been made throughout the drier parts of the subtropics and tropics, including Indonesia and Malaysia.

Uses

For centuries, the seed of jojoba has been eaten raw or parched and was made into a well-flavoured drink similar to coffee. However, its main product now is a liquid wax obtained from the seed. The wax, usually referred to as jojoba oil, and many of its derivatives are widely used in making cosmetics such as hair and skin care products, bath oils, soaps and ointments. In medicine, it is applied to alleviate the effects of psoriasis and other skin afflictions. Jojoba wax and especially its sulphur-containing derivatives are stable at high temperatures which make them very suitable components of industrial oils and excellent substitutes for sperm whale oil as additives in high-pressure and high-temperature lubricants for transformers and gear systems and in metal working as cutting and drawing oils. The liquid wax can easily be converted to a hard wax used e.g. in manufacturing candles. Like sperm whale oil, jojoba oil has anti-foaming properties that can be used in the production of penicillin. Other applications have been found in the manufacture of linoleum and printing inks. New derivatives and uses of jojoba wax are still being developed.

Jojoba oil is not digested by humans and has been tested as a substitute for oils and fats in low-energy foods. Clinical trials, however, found increased levels of several enzymes and of white blood cells, indicating cell damage. It is therefore no longer under consideration as a low-calorie dietary oil.

Jojoba plants are very palatable to livestock, but their growth rate is too low to make jojoba an important fodder crop. Also, jojoba should only form a small part of the diet as all of its parts contain the appetite-depressing toxin simmondsin. The presscake from the seeds contains about 30% protein and is a valuable livestock feed. However, it also contains simmondsin and even after detoxification it is suitable only in limited rations for ruminants. On the other hand, simmondsin may find application in the feed and pet-food industry as an additive to regulate intake of various feed components. It is already marketed as a sports food supplement.

In Mexico, the oil has been used traditionally as a medicine for cancer and kidney disorders and to treat baldness. Some selections are grown in gardens and parks.

Jojoba oil is not digested by humans and has been tested as a substitute for oils and fats in low-energy foods. Clinical trials, however, found increased levels of several enzymes and of white blood cells, indicating cell damage. It is therefore no longer under consideration as a low-calorie dietary oil.

Jojoba plants are very palatable to livestock, but their growth rate is too low to make jojoba an important fodder crop. Also, jojoba should only form a small part of the diet as all of its parts contain the appetite-depressing toxin simmondsin. The presscake from the seeds contains about 30% protein and is a valuable livestock feed. However, it also contains simmondsin and even after detoxification it is suitable only in limited rations for ruminants. On the other hand, simmondsin may find application in the feed and pet-food industry as an additive to regulate intake of various feed components. It is already marketed as a sports food supplement.

In Mexico, the oil has been used traditionally as a medicine for cancer and kidney disorders and to treat baldness. Some selections are grown in gardens and parks.

Production and International Trade

Annual world production of jojoba oil was 1000—1500 t in the middle and late 1990s. The main producers and exporters are Mexico and the United States; smaller amounts are produced in Argentina, Australia and Israel. Production is expected to increase significantly when new plantations come into full production.

The prices of jojoba seed and jojoba oil fluctuated wildly during the 1980s and 1990s from US$ 25 to less than US$ 2 per kg of seeds. During the late 1990s, the price of seed seemed to stabilize at about US$ 2.5 per kg.

The prices of jojoba seed and jojoba oil fluctuated wildly during the 1980s and 1990s from US$ 25 to less than US$ 2 per kg of seeds. During the late 1990s, the price of seed seemed to stabilize at about US$ 2.5 per kg.

Properties

Per 100 g, jojoba seed contains approximately: water 4—5 g, protein 15 g, wax 50—54 g, total carbohydrates 25—30 g, fibre 3—4 g and ash 1—2 g. The wax is clear golden-yellow and consists mainly of esters of long-chain, monounsaturated fatty acids and monounsaturated fatty alcohols (both mainly C20 and C22). The unsaturated bonds are susceptible to chemical reactions such as sulphurization, saturation and isomerization. The wax is comparable in properties to the oil of the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus and its relatives) and oil from the deep-sea fish 'orange roughy' (Hoplostethus atlanticus), but is longer in chain length. The jojoba wax is a natural equivalent of the oil secreted by human skin and can be used to lubricate skin and hair for protection against e.g. ultraviolet radiation.

Jojoba seed meal contains 25—30% crude protein and is rich in dietary fibre. The protein shows an imbalance in the thioamino acids: its cystine content is high while its methionine content is low. All parts of the plant including the seed cake contain the appetite-depressing toxins simmondsin and related cyanomethylene-cyclohexyl glucosides. Simmondsin is especially toxic to non-ruminants and chicken. Rats offered a diet containing 30% jojoba seed meal died of starvation after 2 weeks. A diet containing 10% jojoba seed meal caused a reduction in weight and growth rate, but the rats did not die. When added to the feed of chicken, it causes forced moulting and also interferes with reproduction. In the United States, the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) allows the addition of 5% detoxified seed cake to cattle feed.

In jojoba, long-chain, monounsaturated fatty alcohols act as substitutes of glycerol in the storage of fatty acids. The alcohols are formed by reduction of the homologue fatty acids. The enzyme and the gene coding for it have been identified and have been successfully transferred to Brassica plants.

Jojoba seed meal contains 25—30% crude protein and is rich in dietary fibre. The protein shows an imbalance in the thioamino acids: its cystine content is high while its methionine content is low. All parts of the plant including the seed cake contain the appetite-depressing toxins simmondsin and related cyanomethylene-cyclohexyl glucosides. Simmondsin is especially toxic to non-ruminants and chicken. Rats offered a diet containing 30% jojoba seed meal died of starvation after 2 weeks. A diet containing 10% jojoba seed meal caused a reduction in weight and growth rate, but the rats did not die. When added to the feed of chicken, it causes forced moulting and also interferes with reproduction. In the United States, the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) allows the addition of 5% detoxified seed cake to cattle feed.

In jojoba, long-chain, monounsaturated fatty alcohols act as substitutes of glycerol in the storage of fatty acids. The alcohols are formed by reduction of the homologue fatty acids. The enzyme and the gene coding for it have been identified and have been successfully transferred to Brassica plants.

Description

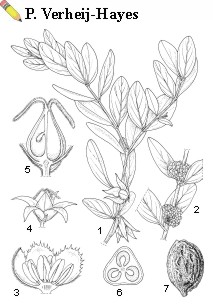

Evergreen, dioecious, multi-stemmed and profusely branching shrub, in moist sites erect, 2—2.5(—6) m tall, in desert sites rounded semi-prostrate, 20—50 cm tall, young parts usually with soft hairs. Leaves thick and leathery, decussate, subsessile; blade ovate to elliptical, 1.5—4 cm x 0.5—2 cm, margin entire, dull dark-green to grey-green, sometimes larger in female plants than in male ones. Inflorescence an axillary, dense, rounded cluster of yellowish male flowers or an axillary, pendulous raceme of 2—20 greenish female flowers or, most often, female flowers solitary; male flowers about 6 mm long, female ones about 13 mm; calyx (4—)5(—6)-lobed, in male flowers with irregular denticulate margin, in female flowers margin entire, accrescent, imbricate, persistent; corolla absent; stamens (8—)10(—12), free, filaments short, stout, anthers basifixed or sometimes ventrifixed, conspicuously extrorse, 4-sporangiate, dehiscing via longitudinal slits, pistil with 3-loculed, superior ovary and 3, free styles. Fruit an ovoid capsule, 1(—3)-seeded. Seed (the 'nut' in literature) ovoid, 1—1.5(—3) cm long, light brown to black; cotyledons thickened; embryo well-differentiated, straight.

Image

| Simmondsia chinensis (Link) C.K. Schneider - 1, female flowering branch; 2, male flowering branch; 3, male flower cut lengthwise; 4, female flower; 5, pistil cut lengthwise; 6, ovary cut transversally; 7, seed |

Growth and Development

After germination, jojoba forms a deeply penetrating taproot (10 m or deeper), which may reach 60 cm before the emergence of the shoot. After the taproot, several deeply penetrating lateral and secondary roots are formed, but lateral spread of the root system is limited. A system of finer feeder roots develops closer to the soil surface. Wild plants may develop into small trees, especially in more humid areas; however, they mostly grow into multi-stemmed shrubs. Jojoba leaves may be shed during severe drought but generally live for 2—3 seasons.

In cultivation, male plants start flowering two years after planting and female ones up to one year later. The difference in time to flowering allows a first roguing of male plants from plantations, thus reducing competition for the female plants. Flowering occurs on new growth only. It is initiated by low temperatures, but flower buds may remain dormant until sufficient moisture is available. Prolonged drought leads to abortion of flower buds and young fruits. Female flowers are mostly produced at alternate nodes, but there are selections that flower at every node.

Jojoba is pollinated by wind. Pollen is produced profusely and flowering male plants are often visited by bees. Pollen grains can travel a distance of over 30 m even with only a light breeze, thereby making pollen distribution very effective. Fruit development takes 3—6 months. In its natural area, flowering occurs between December and April, fruiting between July and October.

The life span of jojoba may exceed 200 years.

In cultivation, male plants start flowering two years after planting and female ones up to one year later. The difference in time to flowering allows a first roguing of male plants from plantations, thus reducing competition for the female plants. Flowering occurs on new growth only. It is initiated by low temperatures, but flower buds may remain dormant until sufficient moisture is available. Prolonged drought leads to abortion of flower buds and young fruits. Female flowers are mostly produced at alternate nodes, but there are selections that flower at every node.

Jojoba is pollinated by wind. Pollen is produced profusely and flowering male plants are often visited by bees. Pollen grains can travel a distance of over 30 m even with only a light breeze, thereby making pollen distribution very effective. Fruit development takes 3—6 months. In its natural area, flowering occurs between December and April, fruiting between July and October.

The life span of jojoba may exceed 200 years.

Other Botanical Information

Formerly, Simmondsia Nutall has been classified in Buxaceae or Euphorbiaceae; it is now generally considered as a monotypic genus in a distinct family, Simmondsiaceae. Pollen morphology, dichotomic branching and stem anatomy support this classification. The anatomy of the stem is characterized by the absence of annual growth rings. Secondary growth occurs in a series of concentric rings. During thickening of a branch, a series of cambia is formed in the secondary perivascular parenchyma. These cambia form vessel elements and fibre tracheids centripetally and conjunctive parenchyma and phloem centrifugally. As one extrafascicular cambium ceases activity, a new cambium is formed through dedifferentiation and division of the outer conjunctive parenchyma cells. Formation of cork tissue is also distinctive in Simmondsia. It starts with the deposition of tannins in the epidermis and cortex; later the adjacent perivascular fibres and parenchyma cells also become filled with tannins. After loss of the epidermis, cortex and outer perivascular fibres, cell division and tannin deposition continue in the transitional zone between the peripheral parenchyma and the cork; a true permanent phelloderm, however, is not formed.

Ecology

The milder, open parts of the Sonora semi-desert form the natural habitat of jojoba. Its spread is restricted to the east by cool highlands, to the north-west by dense shrub vegetation and to the south by thorn forest. Its expansion into areas with a climate more favourable to plant growth seems limited by its susceptibility to grazing. In its natural habitat, it occurs from sea level up to 1500 m altitude, with annual rainfall of about 250 mm in coastal populations and 400 mm for inland populations and with average annual temperatures of 16—26°C. In inland sites with less than 300 mm rainfall, jojoba is only found along temporary watercourses or where run-off water collects. It is tolerant of extreme temperatures; mature plants may tolerate a minimum of —1°C and a maximum of 55°C. Frost damage is common in natural stands and is a major risk in cultivated plants. Seedlings are very susceptible to frost. The higher extreme temperatures have caused scorching of young twigs, leaves and fruits, but not death of plants. Jojoba grows on well-drained sandy, gravelly and neutral to slightly alkaline soils that are often rich in phosphorus. Some selections are tolerant of salinity; they grow and yield well in soils with electric conductivity of 38 dS/m or when irrigated with saline water of conductivity 7.3 dS/m.

Cultivated jojoba is grown in areas with 300—750 mm rainfall. Rainfall higher than 750 mm is likely to increase the incidence of diseases.

Cultivated jojoba is grown in areas with 300—750 mm rainfall. Rainfall higher than 750 mm is likely to increase the incidence of diseases.

Propagation and planting

Early jojoba plantations were established from seed collected from wild stands, but they were not productive enough economically to justify planting. Many new plantations used cuttings from selected plants. When seed is used, germination is good even when seed has been stored for several years. Jojoba seed can be stored in sealed containers at 1.5°C for more than 10 years without loss of viability. Seed is sown in a nursery preferably in slightly alkaline sand at temperatures of 27—38°C. Seedlings need irrigation and should be protected from browsing animals. Transplanting should be done very carefully to avoid damage to the root system and the use of biodegradable containers is advantageous. Methods of rapid in vitro propagation have been developed, but subsequent hardening of seedlings is still a problem. Conventional mutiplication via cuttings does not require special techniques and has given good results.

After land preparation, seedlings are planted at a spacing of about 4.5 m between rows and 2 m within the row, depending on available moisture and mechanization requirements. Where mechanization is not planned, spacing between rows can be less. Hedgerow systems with a reduced spacing within the row have also been proposed.

To ensure adequate pollination, male plants should constitute about 10% of a plantation, but recommendations vary from 5—20%.

After land preparation, seedlings are planted at a spacing of about 4.5 m between rows and 2 m within the row, depending on available moisture and mechanization requirements. Where mechanization is not planned, spacing between rows can be less. Hedgerow systems with a reduced spacing within the row have also been proposed.

To ensure adequate pollination, male plants should constitute about 10% of a plantation, but recommendations vary from 5—20%.

Husbandry

Weeds are the biggest problem in jojoba cultivation and young plantations have to be weeded regularly during the first 3 years after establishment. Where there are grazing or browsing animals, fencing is necessary. Pruning is required to keep the lower branches free from the ground. It is generally started when plants are 1—1.5 years old. Later, pruning of female plants is done in intensive cultivation to obtain an upright shape. For male plants, a broader shape is more desirable. Systems of pruning of young plantations grown from cuttings are still being developed.

Diseases and Pests

In the nursery, the main diseases affecting jojoba seedlings are Fusarium oxysporum and Fusarium solani, but other common nursery diseases have also been recorded. In the field, diseases do not cause economic damage. Grazing animals and rodents are the main pests and in many areas, plantations have to be fenced. A number of insects feed on jojoba and affect growth or production, but none of them has so far developed into a real pest.

Harvesting

Irrigated jojoba plants may start producing fruits in 3 years. Fruits are harvested when mature or nearly so, i.e. about 5 months after flowering. As they do not mature simultaneously, several picking rounds are needed. In many countries, harvesting is done manually, but in the United States, Australia and Israel, harvesting is mechanized. Fallen fruits are picked up from the ground either by equipment using a vacuum system or by a sweeper. When a sweeper is used, fruit is first moved into a central windrow using blowers. The use of tree shakers can increase harvesting efficiency, but may cause damage to the plants.

Yield

In early plantations, jojoba grown from seed yielded only a few hundred kg of seed/ha and could not compete with collections from wild stands. In more recent plantations that used selected clonal planting material, yield may be about 1000 kg/ha under average rainfed conditions and 2000 kg/ha under irrigation.

Handling After Harvest

For storage, jojoba seed requires cleaning and drying to 9—10% moisture content. Extraction of oil from the seed is performed by screw pressing. For many industrial uses, no further refining is needed.

Genetic Resources

The largest germplasm collection of jojoba with over 150 accessions is maintained at the USDA-ARS National Arid Land Germplasm Resources Unit, Parlier, California, United States. Other collections are maintained in Israel and Australia.

Breeding

Genetic variability in jojoba is vast and selection for desirable characters can be carried out in heterogeneous plantations grown from seed of wild plants. Breeding has not yet resulted in the development of true-breeding cultivars, but high-yielding clones have been selected for various growing conditions. Breeding work focuses on yield, oil content and simmondsin content. Additional breeding objectives are frost tolerance and low chilling requirements. Superior clones have been released in Australia, Israel and the United States. High-yielding clones with a low chilling requirement include: Q-106, MS 58-13 and Gvati from Israel.

Prospects

The initial enthusiasm for jojoba as a high-return crop for dry and semi-arid areas has largely faded after many failed attempts to grow it. Jojoba is still a promising crop but the demand for it is much less than anticipated and income from it will be modest. New plantations coming into production will further increase supply and keep prices down. Competition from genetically modified Brassica may also negatively influence the market. Success is still possible, but can only be achieved with proper management and high-yielding plant material adapted to local conditions. As the utilization of jojoba oil in South-East Asia is likely to expand in the future, the feasibility of production for the local market may be even better.

Literature

Benzioni, A., 1995. Jojoba domestication and commercialization in Israel. Horticultural Reviews 17: 233—266.

Benzioni, A. & Forti, M., 1989. Jojoba. In: Röbbelen, G., Downey, R.K. & Ashri, A. (Editors): Oil crops of the world. McGraw-Hill, New York, United States. pp. 448—461.

Bailey, D.C., 1980. Anomalous growth and vegetative anatomy of Simmonsia chinensis. American Journal of Botany 67: 147—162.

Botti, C., Prat, L., Palzkill, D. & Cánavez, L., 1998. Evaluation of jojoba clones grown under water and salinity stress in Chile. Industrial Crops and Products 9: 39—45.

Kleinman, R., 1990. Chemistry of new industrial oilseed crops. In: Janick, J. & Simon, J.E. (Editors): Advances in new crops. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon, United States. pp. 196—203.

Naqvi, H.H. & Ting, I.P., 1990. Jojoba: a unique liquid wax producer from the American desert. In: Janick, J. & Simon, J.E. (Editors): Advances in new crops. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon, United States. pp. 247—251.

Purcell, H.C., Abbott, T.P., Holster, R.A. & Phillips, B.S., 2000. Simmondsin and wax ester levels in 100 high-yielding jojoba clones. Industrial Crops and Products 12: 151—157.

Undersander, D.J., Oelke, E.A., Kaminski, A.R., Doll, J.D., Putnam, D.H., Combs, S.M. & Hanson, C.V., 1990. Jojoba. Alternative field crops manual. University of Wisconsin-Extension, University of Minnesota: Center for Alternative Plant & Animal Products & Minnesota Extension Service, United States. 5 pp.

Weiss, E.A., 2000. Oilseed crops. 2nd Edition. Blackwell Science, Oxford, United Kingdom. pp. 273—286.

Wisniak, J., 1994. Potential uses of jojoba oil and meal - a review. Industrial Crops and Products 3: 43—68.

Benzioni, A. & Forti, M., 1989. Jojoba. In: Röbbelen, G., Downey, R.K. & Ashri, A. (Editors): Oil crops of the world. McGraw-Hill, New York, United States. pp. 448—461.

Bailey, D.C., 1980. Anomalous growth and vegetative anatomy of Simmonsia chinensis. American Journal of Botany 67: 147—162.

Botti, C., Prat, L., Palzkill, D. & Cánavez, L., 1998. Evaluation of jojoba clones grown under water and salinity stress in Chile. Industrial Crops and Products 9: 39—45.

Kleinman, R., 1990. Chemistry of new industrial oilseed crops. In: Janick, J. & Simon, J.E. (Editors): Advances in new crops. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon, United States. pp. 196—203.

Naqvi, H.H. & Ting, I.P., 1990. Jojoba: a unique liquid wax producer from the American desert. In: Janick, J. & Simon, J.E. (Editors): Advances in new crops. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon, United States. pp. 247—251.

Purcell, H.C., Abbott, T.P., Holster, R.A. & Phillips, B.S., 2000. Simmondsin and wax ester levels in 100 high-yielding jojoba clones. Industrial Crops and Products 12: 151—157.

Undersander, D.J., Oelke, E.A., Kaminski, A.R., Doll, J.D., Putnam, D.H., Combs, S.M. & Hanson, C.V., 1990. Jojoba. Alternative field crops manual. University of Wisconsin-Extension, University of Minnesota: Center for Alternative Plant & Animal Products & Minnesota Extension Service, United States. 5 pp.

Weiss, E.A., 2000. Oilseed crops. 2nd Edition. Blackwell Science, Oxford, United Kingdom. pp. 273—286.

Wisniak, J., 1994. Potential uses of jojoba oil and meal - a review. Industrial Crops and Products 3: 43—68.

Author(s)

L.P.A. Oyen

Correct Citation of this Article

Oyen, L.P.A., 2001. Simmondsia chinensis (Link) C.K. Schneider. In: van der Vossen, H.A.M. and Umali, B.E. (Editors): Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 14: Vegetable oils and fats. PROSEA Foundation, Bogor, Indonesia. Database record: prota4u.org/prosea

All texts are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Netherlands License

This license does not include the illustrations (Maps,drawings,pictures); these remain all under copyright.